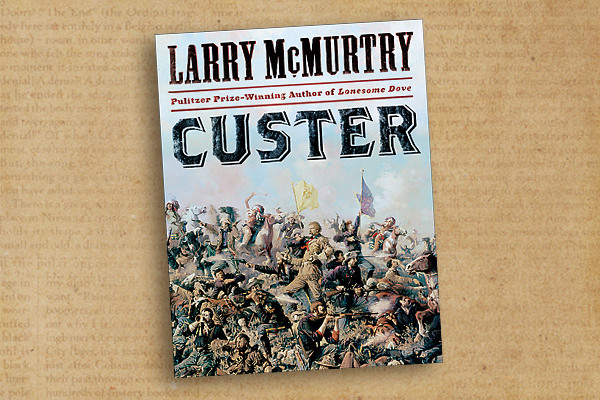

More a study of cultures in collision than an attempt to set records straight or expose new findings about George A. Custer, Larry McMurtry’s Custer presents a “short life” of the frontier legend.

More a study of cultures in collision than an attempt to set records straight or expose new findings about George A. Custer, Larry McMurtry’s Custer presents a “short life” of the frontier legend.

As the author tells us, “Several times, over the years, I have been asked to write a life of Custer, and have declined mainly because I found Evan Connell’s Son of the Morning Star a masterpiece that is unlikely to be bettered.” But at length he proceeded, because the “short life itself is a lovely form, a form that was once common in English letters. One of the duties of the short life is to bring clarity to the subject.”

In this slim volume, packed with photographs and reproductions of period artwork, McMurtry brings his clarity by etching the cultural milieu that shaped not just Custer, but his times. Wisely, he sets his own limits: “If you seek details of the battle itself, I refer you to Evan Connell, Robert Utley, James Donovan, and Nathaniel Philbrick, who, between them, sweep in virtually everything verifiable about the battle.”

McMurtry does tell the story, even of the Little Big Horn, but in broader brush strokes. Still, this is not “history lite.” You’ll find meat here, but this is a 21st-century book for a 21st-century audience. On mobile devices, the plenitude of photos will play well—digital fare turns photography into a highly affordable splurge, not just for publishers, but also for book buyers.

The author has purged the pedantry and distilled the essences. It’s rife with curiosities. One learns, for instance, that on his final expedition, “Custer wrote letters constantly—Libbie [wife] mentions one of 42 pages, and in fact, quite a few reached 40 pages.” We also learn that only an hour or two after the battle, native scouts to the south, in Crooks’s command, which was more than a day’s ride away, were wailing and expressing a sense of calamity; that Buffalo Bill Cody, as showman, employed Indians who had helped kill Custer.

I stated that the author deals in broad strokes, but it could equally be stated that he does the opposite—that he paints his pictures with the clever aside, the telling detail, the adroit observation. He juggles anecdotes almost as blithely as Ian Frazier does in Great Plains. McMurtry’s trademark droll humor is fully engaged—the underlying tension makes it zing. I zipped through this book. It stays at a lope. It entertains.

Yet it does, ultimately, express a motif purely its own. Custer features a strain of fatalism that has always permeated McMurtry’s writings on the West. That fatalism tinges his fiction and his nonfiction besides. It suffuses Lonesome Dove, but rather than burdening that book, it ennobles it. That fatalism wends its way up the Missouri River in “Sacagawea’s Nickname.” And it shadows the 7th Cavalry, and the Plains tribes as well, in Custer. Shadows, yes, and eventually devours. Meanwhile, McMurtry tries neither to redeem Custer, nor to make an enigma of him. His targets are the times and the place and the human ethos, not the solitary trooper riding to a tragic end.

—Jesse Mullins