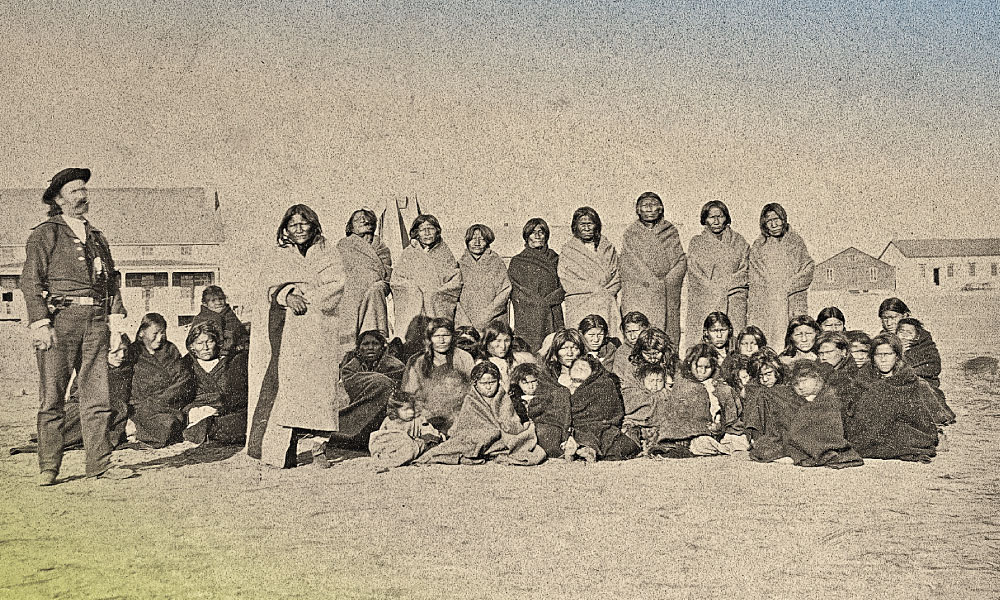

– Illustration Courtesy Library of Congress; all other photos True West Archives –

The 19th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry fought the harsh elements and rough terrain, but never the American Indians.

The Sunflower State found a soldier willing to engage the Indians in Lt. Col. George A. Custer. On November 29, 1868, military leaders learned of Custer and his 7th Cavalry’s victory at the Battle of Washita two days earlier.

So in early March 1869, when Custer requested volunteers to accompany the 7th Cavalry on a new expedition, the Company L unit of the 19th Kansas Volunteers believed they would finally see some action.

The Path to Glory

From the start of the year through the summer of 1868, marauding Indians had murdered 110 whites, raped 13 white women, stolen 1,000 livestock and destroyed private property in Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s Department of the Missouri. Many of the depredations were perpetrated in north-central Kansas and along the Kansas-Colorado border by the Southern Cheyennes.

On August 17, Kansas Gov. Samuel J. Crawford offered to raise state volunteers to curb the Indian violence. Sheridan accepted the offer on October 9 and requested the governor raise one volunteer regiment of cavalry to serve for six months. The federal government would pay the regiment the same pay as soldiers in the Regular Army and furnish the men with rations, equipment and weapons.

Crawford recruited a mounted unit of volunteers from the state militia and designated the new formation the 19th Kansas Cavalry. On October 21, he set up Camp Crawford, in Topeka, to organize the new recruits.

Within weeks, 1,300 men, including former Union Civil War cavalrymen, were mustered into the regiment, while supplies, equipment and horses arrived from Fort Leavenworth. The lieutenant colonel in charge of training was Horace L. Moore, 31, a veteran volunteer cavalry officer who had commanded the Union 4th Arkansas Volunteer Cavalry regiment and, in 1867, served as a major in the 18th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry. Crawford, 33, a former major general for the Union Army during the Civil War, resigned his governorship in early November and assumed command of the cavalry.

On November 5, ten of the 12 companies of the regiment left camp to march to Camp Supply, on the south bank of the South Canadian River, 355 miles from Topeka. (The other two companies, D and G, marched to Fort Hays.)

The trip was supposed to take five days, so the 1,100 men carried rations for that length of time. But the journey took longer, leaving the soldiers to purchase sustenance for themselves and their mounts from inhabitants in Emporia. On November 12, when the soldiers reached Fort Beecher on the Little Arkansas River, their hopes for relief were dashed upon learning that the post did not have enough food, forage or wagons for the regiment.

Adding to the distress of inadequate rations, the force was about to enter what was known as “that land across the river whence no traveler had returned.” Not a man in Crawford’s command had ever been south of the Arkansas River.

The soldiers faced a journey through 160 miles of desert. The horses ate the last of the forage on November 16. The men were supplementing their food supply with daily kills of buffalo.

The regiment entered Indian Territory on a rainy November 19 and made camp that night along Salt Fork Creek. The wind increased to hurricane force, with temperatures falling to below zero. The wind prevented fires from being lit that evening, leaving the men suffering greatly from the cold. Only at 3 a.m., when the men burned a log in a pit they dug, did they successfully find warmth from a fire.

The situation became critical on November 22. The soldiers could not find any buffalo to slaughter. Heavy snow falling restricted the men’s vision to 20 yards. They made camp near Sand Creek, with their only shelter from the brutal winds being dog tents—six-foot-long, five-foot-wide affairs made of thin ducking.

That night, with 10 inches of snow on the ground, and more falling, Capt. Allison J. Pliley, commanding Company A, with 50 men, left the regiment to find Camp Supply, which was supposed to be “somewhere near the forks of Beaver creek and the North Canadian.” Pliley had served as a ranker in the 15th Kansas Cavalry during the Civil War and as an Army scout during 1867 to 1868.

Camp Starvation

The rest of the troopers woke up on the morning of November 23 to find a foot of snow on the ground and more coming down. All sense of direction was lost. Troopers hunkered down, cutting down cottonwood trees for firewood, which the famished horses stripped of every twig and inch of bark.

The next day, the snow stopped and the troopers moved out in a foot and a half of the white stuff, leading their horses. After five tortuous miles, the men came to the Cimarron Hills and went into bivouac. The area abounded with Hackberry trees, providing fruit seeds that the famished men devoured. Their desperate situation was starting to become clear, and the men christened the site “Camp Starvation.”

To ease the supply problem, the leaders decided to divide the column. Colonels Crawford and Moore took nearly 500 of the strongest men and horses to look for Camp Supply, while the remaining 600 or so men stayed with the wagons at Camp Starvation, in the hopes Capt. Pliley had found Camp Supply and relief was on its way.

On November 25, Crawford and Moore began the march, crossing the 200-yard-wide, three-foot-deep Cimarron River, which ran through a gorge 500 feet deep. Private James A. Hadley, Company A, who accompanied Crawford, recalled the temperature dropped to 20 degrees below zero. The next day, Thanksgiving, horses began to die of starvation.

On November 27, the men struggled through deep snow over hilly prairies and reached the North Canadian River. The next day, Crawford’s column entered Camp Supply after 24 days on nine days of subsistence and seven days of forage, having traveled 355 miles from Topeka. They had lost 75 horses, but no men. Pliley had gotten there three days before, and a relief expedition was already on its way to Camp Starvation. The detachment left behind at Camp Starvation reached Camp Supply on December 1.

Custer Enters the Picture

By the time the 19th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry reached Camp Supply, Gen. Sheridan had already feared the worst, having heard no news from them. He enlisted Custer and his 7th Cavalry to join the fight.

This news was a great disappointment to the boys from the Sunflower State, since they had yet to find glory in battle against the Indians. As Pvt. Hadley stated, “…they feared the enterprising Custer would strike so vigorously that the Indians would roar for peace.”

Their suspicion was confirmed on November 29, when they learned of Custer’s victory at the Battle of Washita two days earlier. The volunteers were now on a mission to accompany the 7th Cavalry to secure peace.

Starting on December 7, along with Sheridan, the 1,800 troopers of the 7th and 19th Cavalry regiments journeyed through a series of snow blizzards and below-zero-degree weather over the ice-covered, half-mile-wide, four-foot-deep South Canadian River to inspect the Washita battlefield. After marching through 15 inches of snow, they reached Fort Cobb, located along the Washita River, on December 18 and remained there until January 6, 1869.

Large numbers of troopers were now disabled by frostbite. The 19th Cavalry had lost 150 horses due to the weather and lack of forage.

Sheridan persuaded elements of the Arapahos, Kiowas and Comanches to enter into peace talks with the Army. That the military was threatening to hang prisoners Lone Wolf and Satanta, two principal war chiefs of the Kiowa nation, did much to facilitate negotiations. The ploy was effective. By the time the Army released the prisoners in February, most of the Kiowas had returned to their reservation.

Another Shot at Glory?

In early March, Custer wanted to take his command, now at Fort Sill, to the southwest, toward the Red River, in order to seek out bands of Cheyennes. The hard campaigning, however, had reduced his 7th Cavalry by a substantial number of men—about 450—and left only 200 fit horses.

Custer requested volunteers from Lt. Col. Moore, who had taken command of the 19th Kansas after Col. Crawford resigned and left the regiment on February 15. Moore polled his men for volunteers who would be led by the colonel and by Company L Capt. Charles H. Finch.

Getting those volunteers was difficult, not because men did not want to go, but because so many were unfit for duty due to the past four months of hard marching and exposure to the harsh weather. The regiment’s ranks were further reduced because 300 of its members were so unfit for active duty that they, under First Lt. Henry E. Stoddard, were being marched, along with invalids from the 7th Cavalry, back to a base camp on the Washita.

In the end, 450 men and officers of the 19th Kansas elected to go with Custer. On March 2, the volunteers, on foot, and the 7th Cavalry started a mud march from Fort Sill to confront the Cheyennes. Custer, impressed with the Kansas Volunteers’ march discipline, wrote that the “Nineteenth put to the blush the best regular infantry.”

After crossing the Red River, the column traveled through desert country. Rations had been reduced twice by then, and the men were getting hungry. On March 8, the pace of the march was quickened even though rations had been reduced once more. When the mules started to die, the men ate mule meat.

As the blue column moved, a string of exhausted men on foot was left in its wake. They had destroyed their wagons, carrying the men’s gear, since the demise of the mules left the wagons unmovable.

On March 17, after a freezing night, the soldiers spotted an Indian trail that led to the northeast. Word moved down the column that a fight with hostiles would probably occur in a day or two.

The five days of rations lasted for 16 days, and on March 18, the food supply ran out. Two days later, the starving force of more than 1,000 soldiers found a village, containing 250 lodges and about 1,500 Cheyennes, near today’s Wheeler County in Texas.

Fired with anticipation of a battle against Indians, the officers and men of the 19th Kansas were dumbstruck when told of Custer’s order, “Don’t fire on those Indians.”

The men took their stations—the 19th at the head of the valley, and the 7th at the lower end—within easy shooting distance of the village, while Custer entered the camp to negotiate with the Cheyennes. He demanded that they return to their reservations and insisted they release two white female captives.

During the parley, 30 troopers—15 each from the 7th and 19th Cavalries—strolled down to where the talks were being held. Custer ordered them to arrest leaders Dull Knife, Medicine Arrow, Fat Bear and Big Head, stating they would be hanged unless their people complied with his demands.

On March 22, the Cheyennes handed over the ladies, unharmed.

The next day, Custer marched his command back to the Washita battlefield area. The only protections the men had from the biting cold were the worn clothes on their backs and one thin blanket, 19th Kansas Pvt. David L. Spotts recalled.

With no water around in the desolate plain and the men growing weaker by hunger, Custer sent a request for aid to a supply point on the Washita and waited for the relief force. All of the 19th’s men remained with Custer except the redoubtable Pliley, who marched his tired, threadbare and bootless men to the supply encampment about 40 miles distant.

On March 27, the last of the 7th and 19th Cavalries arrived at the supply base. The command had survived nearly a month on five days of rations and achieved all its objectives. The 19th Kansas transferred to Camp Supply, then embarked, on foot, on a 200-mile trek to Fort Hays. A week out from Camp Supply, on April 10, the troopers reached Fort Hays. On April 18, the members of the 19th Kansas Cavalry were mustered out of service.

Out of 50 officers and 1,300 men in the 19th regiment, four died of hunger and cold, another was killed and a fifth met his death due to a gunshot accident. During the course of the regiment’s sufferable existence, only 90 members deserted.

Overshadowed by the fabled 7th Cavalry and its leader, Custer, the Kansas horse soldiers should be given their due. Although they fought no battles during their service, they did endure great physical privation, marched about 950 miles over harsh terrain and in miserable weather, and performed every task expected of them.

Arnold Blumberg is an attorney in Baltimore, Maryland, and the author of When Washington Burned: An Illustrated History of the War of 1812. He is working on a book detailing the decisive American Indian campaigns waged by the frontier U.S. Army.