David Crockett wore many hats during his lifetime (1786-1836) beside his trademark coonskin.

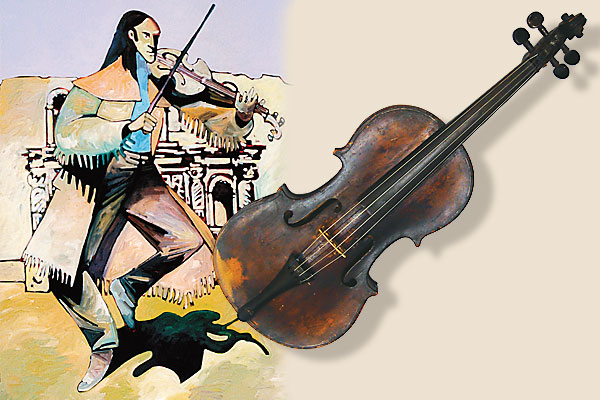

He is remembered as a farmer, hunter, volunteer soldier, scout, state legislator, U.S. Congressman, author, father, husband and Alamo hero. Recently, another side of Crockett has been driven home with increasing frequency in books, art, illustrations and movies—that of a musician. A frontier fiddle, also known at the time as a “devil’s box,” now has taken its place alongside the coonskin cap and Kentucky Long Rifle as symbols of the Tennessee hero.

Crockett himself is a symbol within the larger story of the Alamo. Depending upon the predilections of those writing about him, Crockett either can be a paragon of frontier virtue and nobility, or an arrogant spearhead of Manifest Destiny. He can die magnificently at the Alamo, fighting to his last breath, or be executed after humbly waiting for his captors to dispatch him at their will. He can be a leading figure or a sort of “aw-shucks” high private who lingers in the background.

The same dichotomy can be said about representations of his fiddle playing. Crockett can be portrayed as playing a quiet, sentimental tune, lulling the men of the Alamo into a rich nostalgia for home and family, or sawing out a raucous reel or jig causing any number of doomed Alamo defenders to break into spontaneous dance. Of the two, the latter is probably truer—not necessarily to fact. The story of the legendary Alamo almost demands Crockett assume the roll of a merry trickster—playing fiddle tunes, dancing jigs, telling stories and generally laughing in the face of death as the enemy’s noose tightens.

Billy Bob Thornton’s Crockett, in the 2004 Touchstone film The Alamo, is given the opportunity to showcase both sides of the frontiersman’s fiddle persona. He scratches out a lively version of “Listen to the Mockingbird Sing” at a fiesta prior to the Alamo siege. Critics of the film point out that this musical selection is anachronistic, adding to a number of complaints about historically inaccurate details of the production.

Yet the song and its performance (played on-camera by Craig Eastman) effectively capture the mood director John Lee Hancock hoped for—that of a light-hearted Crockett, thumbing his nose at death.

Later, during the Alamo siege, the Mexican army’s band serenades the Alamo defenders with an orchestral rendition of the bugle call “Deguello,” supposedly played at the Alamo and promising no quarter for the besieged. In a beautifully played scene, Thornton’s Crockett mounts the Alamo’s wall with his trusty box, picks up on the melody and sends it back to the Mexican troops as “Deguello de Crockett.”

His soulful piece works on two levels. In mimicking the hymn of no mercy, Crockett proclaims the Texans’ defiance and announces he and his companions intend to give as good as they get. On the other hand, the hymn conveys an anti-war message, showing that the Texans and Mexicans are more alike than not, through the commonality of the music. Both sides are mesmerized into quiet reflection by the tune.

Did Crockett actually play the fiddle? Did he carry one to Texas with him? Did he really entertain the doomed Alamo garrison with it? A number of accounts suggest that he did.

Fiddlesticks—or not?

The basis for this growing legend first appeared in James M. Morphis’ The History of Texas from its First Discovery and Settlement in 1875, 39 years after the battle, as a quote attributed to Alamo survivor, Susanna Dickinson. As the wife of Alamo defender Almeron, she endured the 13-day siege, surviving with the couple’s infant daughter, Angelina. Morphis, reported Dickinson as saying, “Col. Crockett was a performer on the violin, and often during the siege took it up and played his favorite tunes.”

Another bit of evidence came to us more circuitously. In the early 1930s, Amelia Williams used Susanna Arabella Sterling (nee Griffith), granddaughter of Dickinson, as a source for her doctoral dissertation, “A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and of the Personnel of its Defenders.”

Sterling, close to 70 years old at the time of the interview, related stories about the Alamo her grandmother had entertained her with while Sterling was a child and young woman. One such story she shared with Williams was that of Alamo defender, John McGregor. “One story that always amused her,” Williams wrote, “was Mrs. Dickerson’s [sic] account of John McGregor and his bagpipes. She said that when the fighting would lull, and the Texans had time for rest and relaxation, John McGregor and David Crockett would give a sort of musical concert, or rather a musical competition, to see which one could make the best music, or the most noise—David with his fiddle, and John with his bagpipes. She said McGregor always won so far as noise was concerned, for he made ‘strange, dreadful sounds’ with his queer instrument.” Later on in her dissertation, Williams added that Crockett “often ‘played tunes on the fiddle’ when the fighting was not brisk; and that sometimes he played in competition with John McGregor’s bagpipes.”

No one knows if these stories are accurate depictions of scenes enacted in the Alamo or simply stories told by a grandmother to entertain her young grandchild. It is possible that this story may have become embellished in the process of being relayed from Dickinson to Sterling to Williams over a span of 60 years. We also do not know how accurate Williams’ transcription of the story may have been, as other information she gave regarding Sterling is questionable. For example, Williams described Sterling as having died in August 1929 at the age of 83. Records indicate that Sterling passed away on July 17, 1929, at 74 years old.

Another claimant to Alamo fame, Andrea Castañon de Villanueva, supposedly commented on Crockett playing a fiddle. The celebrated Madam Candelaria, as she became known, enthralled visitors to San Antonio with tales of the siege and battle, and her care for the ailing James Bowie. At least three of her stories appeared in newspapers in the 1890s. Only the last one, published the year of her death, contains the statement, “They had supper at my hotel and there was lots of singing, story telling and some drinking. Crockett played the fiddle and he played well if I am any judge of music.” (Since Candelaria’s accounts all tell varying stories of the Alamo, she is considered less than a credible source by historians today.)

A fourth source describing Crockett’s musical skills comes from Robert Hall, an early Texas settler, who published his memoirs in 1890 and wrote of Crockett playing a fiddle at a frolic in Tennessee before leaving for Texas. The tale is somewhat less than reliable since the editor of a modern edition of the memoirs cautions readers not to rely on everything written by Hall, who is described as part of a breed characterized as “authentic liars.” One has to wonder why the editor republished the memoirs in the first place.

Other factors raise doubts about whether or not Crockett was the frontier fiddler legend needs him to be. Crockett published his autobiography, A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett, in 1834. Although he goes into great detail about his childhood, courtship rituals, bear hunting, horrors of the Creek Indian War of 1813 and his entry into politics, he never once mentions owning, learning to play or actually playing a fiddle. The same holds true for his 1835 An Account of Col. Crockett’s Tour to the North and Down East, ghostwritten, but with information on his trip supplied by Crockett himself. Nor is there any mention of fiddle talent or ownership in his correspondence.

A number of people witnessed Crockett leaving Tennessee for Texas in 1835. Some described his clothing, his appearance, his personality. Others told of seeing him wearing his coonskin cap and carrying his rifle. At least one gives the details of a raucous going-away party Crockett attended on his last night in Memphis. None, however, describe him as carrying or playing a fiddle.

Non-combatants, other than Susanna Dickinson and her daughter, survived the Alamo siege and battle. Two of them, Juana Navarro Alsbury and Enrique Esparza, left a number of accounts in later life but neither one mentions Crockett as having played a fiddle. Nor do they convey any recollection of any defender playing something as exotic as bagpipes in the Alamo, much less musical duels with fiddles.

Tracking the Lineage

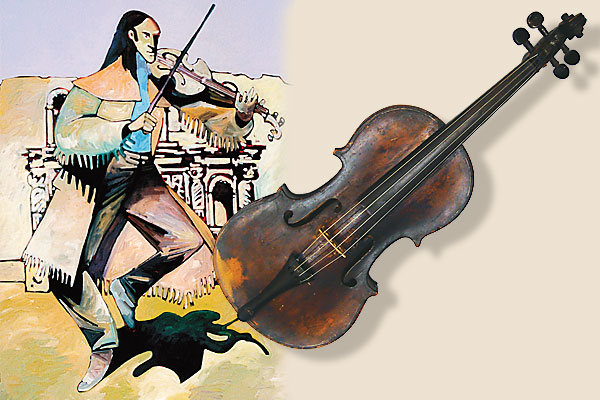

Whether or not Crockett owned or played a fiddle, instruments have emerged, over the years, purported to have been owned by him. One resides in the collection of the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Texas. Loaned to the Witte in 1934, it was donated to the museum 16 years later by C.K. Quin, a judge and former mayor of San Antonio. He obtained it from a Russellville, Alabama, violin maker and repairer, T.S. Quinn (no relation). T.S. Quinn bought the instrument from Frank A. Hollis, who inherited it from his father, Tom, who claimed to live near the Crockett homestead in Franklin County, Tennessee. According to the lineage, David Crockett’s son, Joseph, gave the fiddle to Tom Hollis in 1859. Inside the instrument, in faint pencil, are the words, “This fiddle is my property, Davy Crockett, Franklin County, Tenn. Feb. 14, 1819.” Crockett did not have a son named Joseph nor did he live in Franklin County, Tennessee, in 1819, both of which raise questions about the violin’s authenticity.

Originally, the violin maker set a price of $30 but then donated it to Quin for his service as mayor of San Antonio. He also provided affidavits by himself and Frank A. Hollis attesting to the truth of their stories, but hearsay doesn’t go far in proving the authenticity of the fiddle.

Before violin maker Quinn sent the instrument to Mayor Quin, he replaced the tail piece and finger board, re-bored the holes and added new pegs, and put on a bridge and new strings so that the fiddle arrived in playable condition. He included in the package the original tail piece and finger board, as well as two small rattlesnake rattles that he claimed were inside the fiddle when he received it.

The Witte Museum remains cautious about the instrument, treating it as a fiddle possibly owned by Crockett. If its interesting history is true, it probably could better be described as a fiddle including parts of one that once belonged to Crockett.

A 1982 typed description of the fiddle by Bill Green, included in the museum’s papers, states, “It is also possible that the violin is authentic and that T.S. Quinn or Frank A. Hollis hoped to support the instrument’s authenticity by writing inside the instrument. Or, the instrument could be a fake.”

In 2002, with special permission from the Witte, musician Dean Shostak recorded a CD featuring tunes he played on the fiddle. Although titled Davy Crockett’s Fiddle, a label on the cover of the CD states, “Featuring the fiddle that is believed to have belonged to Davy Crockett (1786-1836).” Shostak is still authorized to play this fiddle, which he does occasionally, in live performances.

Second Fiddle to None?

If the parts of the fiddle in the Witte Museum are those once owned by Crockett, surely they could not be parts of one supposedly carried to the Alamo. Perhaps Crockett had two fiddles; a belief fostered by the owner of yet another “Crockett” fiddle.

When the instrument owned by Mayor Quin began receiving publicity for the Texas Centennial in 1936, 80-year-old John Houston Thurman of Longview, Texas, came forth with a devil’s box of his own to challenge the original. Along with his fiddle came a history much more colorful than that of Quin’s, and it purportedly linked the instrument right back to the Alamo.

Thurman’s fiddle was the one Crockett carried to the Alamo, reported an April 19, 1936, article in The Houston Chronicle. After the battle, a Mexican soldier took it to Mexico City as spoils of war. Of course, this would have to have been a Mexican soldier who was not part of the force decimated and captured by Sam Houston’s army six weeks later in San Jacinto.

The article explains that an American soldier in Gen. Winfield Scott’s army during the Mexican War found the instrument in Mexico City in 1847, which he quickly sold. John Houston Thurman’s father, also in the Mexican capital at the time, discovered the fiddle in a secondhand store, bought it and returned to Texas with it in 1848. The fiddle remained in the Thurman family’s possession until 1864 when thieves broke into their home and made off with it.

By 1892, the elder Thurman had passed away and John Houston Thurman was operating a traveling entertainment show. Unfortunately, the show found itself in Parsons, Kansas, in dire need of musical instruments. What happened to their original instruments or how they operated their show without them up to this point is never explained.

As Thurman, described as a “merry-eyed old man,” perused a selection of instruments on the walls of a secondhand store, what should he find but the very David Crockett fiddle his father had brought home from Mexico City so many years before!

How could Thurman have recognized it as the same fiddle? One side of the instrument’s head bore the carved inscription, “D. Crockett,” and the other, “Tenn., 1835, D.C., Texas 1836.”

But how do we know Crockett really owned the fiddle? According to the Chronicle article, an “old Negro neighbor” of the Alamo defender, reportedly still living in 1936 (which would have put him well over 100 years old), confirmed that “David Crockett had a habit of carving his name with a pen knife on practically everything he owned.”

The Legend of a Fiddle

David Crockett may or may not have played the fiddle. If he did, he remained uncharacteristically quiet about it all of his life. He may or may not have carried a fiddle with him to Texas. If so, no one who saw him on his way ever reported it. He may or may not have played the fiddle to keep up the spirits of the men of the Alamo. In the Alamo of legend, he certainly did.

Some may call the whole tale of Crockett and his fiddle a lie, but as John Steinbeck wrote, “A thing isn’t necessarily a lie even if it didn’t necessarily happen.”

We need Davy Crockett up on those walls with his fiddle.

William Groneman III grew up in Howard Beach, NY, and spent 25 years as a member of the New York City Fire Department. He is the author of Forge Books’ David Crockett: Hero of the Common Man.

https://truewestmagazine.com/the-outlaw-davy-crockett/