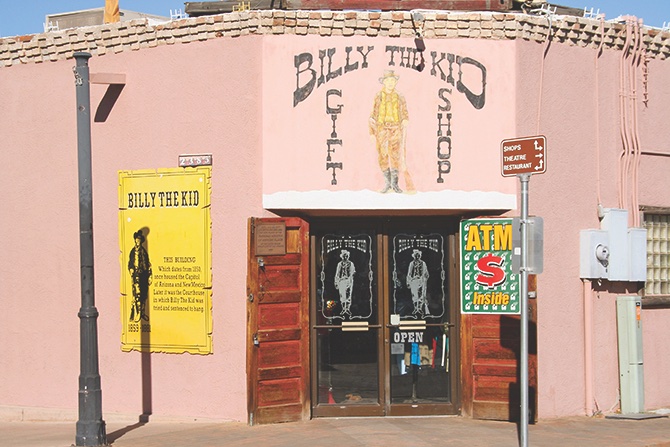

Tracking the legend across Arizona and New Mexico is still an adventure.

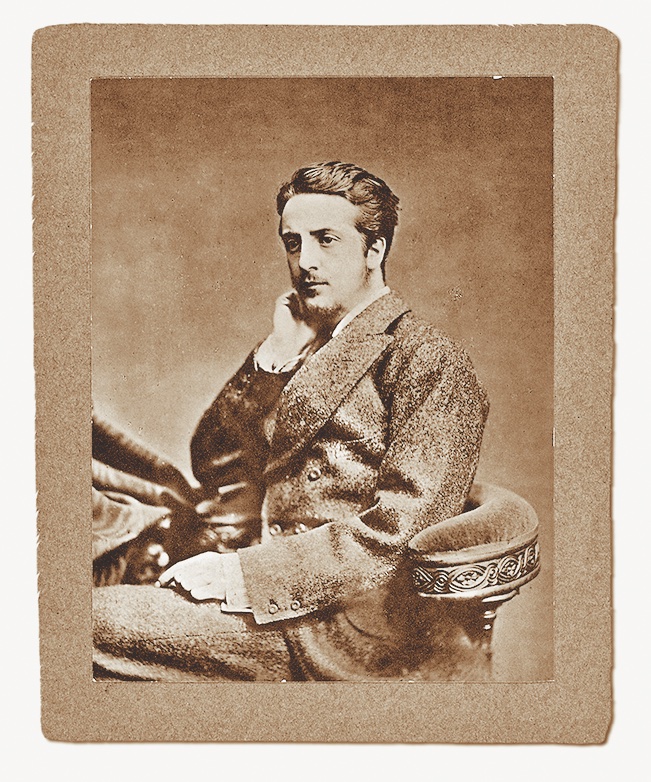

It’s easy to start a travel story when you know where your subject was born. Mark Twain? Florida, Missouri. Billy the Kid …?

“Billy the Kid was reportedly born all over the world,” says Melody Groves, author of Before Billy the Kid: The Boy Behind the Legendary Outlaw. “First is Ireland, supposedly coming over with his mom—in 1846, like she did? I’ve read New York City, Indianapolis, and my favorite is Lincoln, New Mexico.”

According to the 1880 census, William H. Bonney was born in Missouri. Billy wouldn’t, it’s argued, lie to a census official. Well, he lied about his name (Henry McCarty).

“Personally and logically,” Groves says, “I believe he was born in Utica, New York, May 1861. “All my research points there, and indeed Billy said he thought he was born in 1861.”

That’s why I’m starting in Silver City, New Mexico.

The Early Years

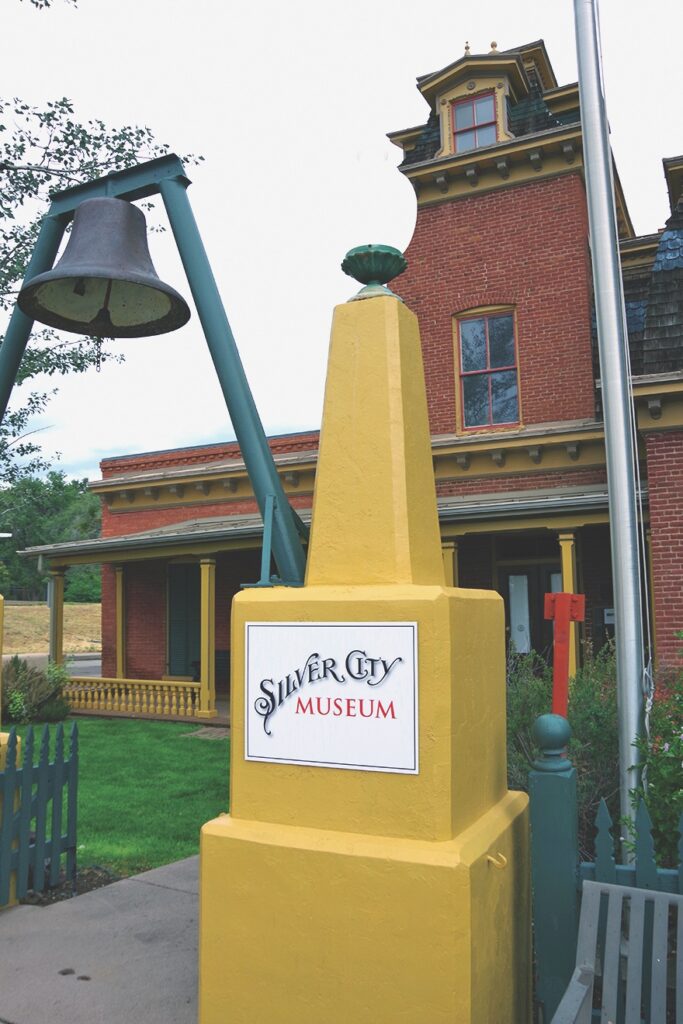

Yes, Billy can be placed in Anderson, Indiana, and Wichita, Kansas. Sure, his mother, Catherine McCarty, married William H. Antrim in Santa Fe, New Mexico, on March 1, 1873, then traveled with Billy and his brother Joseph roughly 300 miles southwest to Georgetown. But by early summer, the Antrims had settled in Silver City (Silver City Museum). And that’s where the legend begins.

“Silver City is the liveliest town in the country; is rapidly growing, and will ere long be the metropolis of the Territory,” Santa Fe’s Weekly New Mexican reported on April 1, 1873.

Antrim wasn’t much of a miner, carpenter, butcher or gambler. Catherine, however, worked hard, baking pies and sweetcakes, doing laundry and taking in boarders to keep the family afloat. A good student in school, Billy loved to sing and dance. But things went south when Catherine died of tuberculosis on September 16, 1874.

Antrim sold Catherine’s cabin. He farmed the boys out to blacksmiths and butchers. So Billy began running with a petty thief called Sombrero Jack. About a year after his mother’s death, clothes stolen from a laundry were found in Billy’s room, and he was jailed. But the slender lad escaped through the chimney and fled to Arizona Territory.

He reappeared in history at Fort Grant, Arizona, on August 17, 1877, when he entered a saloon and got into a row with blacksmith “Windy” Cahill. “I had called him a pimp and he called me a son of a bitch; we took hold of each other,” Cahill said in his deathbed statement.

One witness said Cahill had Billy pinned on the floor and was slapping his face, and when Billy yelled, “You are hurting me. Let me up,” Cahill said, “I want to hurt you. That’s why I got you down.” But Billy freed one of his hands, pulled a revolver, shot the bully, ran outside, stole a horse and vamoosed.

Entering Lincoln County

Ballets, biographies, screenplays, novels and tourism brochures aren’t written about laundry thieves and bully killers. But by the fall of 1877, Billy was cowboying for a transplanted Englishman chasing the American dream.

In addition to ranching, John Tunstall decided to go into business with attorney Alexander McSween, with some assistance from cattleman John Chisum, and opened a store in Lincoln, the sprawling county’s seat (17 buildings comprise the outstanding Lincoln Historic Site). The downside of that was that Tunstall’s store was competing with The House, a mercantile run by Lawrence G. Murphy and James Dolan that also controlled government contracts and was backed, many argue, by the powerful (and corrupt) Santa Fe Ring.

What followed is so complicated you have to read everything Bob Boze Bell, Maurice Fulton, William Keleher, Frederick Nolan and Robert Utley have written on the subject, and you’ll still be confused.

On February 18, 1878, a posse sent by Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady caught up with Tunstall—whose hired hands, including Billy, were chasing turkeys—and shot him and his horse dead.

So McSween persuaded John B. “Squire” Wilson, a justice of the peace, to swear in Tunstall supporters as

constables—they called themselves “Regulators”—and Lincoln County found itself answering to McSween’s law and the law of Brady, i.e., The House.

Regulators caught and killed two members of the posse that murdered Tunstall. Also left dead was a Regulator who protested too much, was thought to be a spy or just had a lousy day. On April 1, Brady and Deputy George Hindman were killed in an ambush in Lincoln. A few days later, Andrew “Buckshot” Roberts was mortally wounded in a gunfight at Blazer’s Mill, but he killed Regulator leader Dick Brewer and wounded a few others.

Lincoln County had spiraled deeper into anarchy when the Lincoln County War ended, more or less, after McSween and Regulators returned to Lincoln, fortifying his home and other buildings and beginning the “Five-Day War.” That ended July 19 when House gunmen set McSween’s house afire. Billy and some companions made it out alive, but McSween died with several others. “The Big Killing” was over. So was President Rutherford B. Hayes’s patience.

Hayes replaced New Mexico Governor Samuel B. Axtell with Lew Wallace, who thought he had ended the war by declaring amnesty for all parties not facing indictment. Tough luck for Billy, charged with killing Brady and Roberts. But Billy saw a way out.

In short, Billy and Wallace agreed on a deal. Billy would be pardoned if he testified in a court of inquiry at Fort Stanton (Fort Stanton Historic Site) about Col. Nathan Dudley’s actions, or lack thereof, during the Five-Day War. Billy lived up to his end of the deal, too. But seeing things weren’t going his way in the military court, he skedaddled.

End of the Trail

Billy gambled, rustled and danced with his sweethearts. He killed Joe Grant in a Fort Sumner saloon in 1880. He rode into an ambush led by newly elected Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett on December 19, 1880, and surrendered a few days later at Stinking Springs, having lost two pals, Tom Folliard and Charlie Bowdre, to bullets.

Garrett hauled his prisoners to Las Vegas (City of Las Vegas Museum and Rough Rider Memorial Collection), and took the train to Lamy and the spur to Santa Fe, where Governor Wallace, soon to be famous as Ben-Hur’s author, ignored Billy’s reminders of a promise.

Sent to Mesilla, Billy stood trial for killing Brady, was convicted, sentenced to hang and returned to Lincoln.

But in another plot twist, Billy escaped, killing deputies James Bell and Robert Olinger.

Wallace posted a $500 reward for Billy’s capture. And on July 14, 1881, Garrett was waiting in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom at Fort Sumner when Billy entered and Garrett killed him.

Killed the young man born in…wherever. But his legend lives forever.

A Wide Spot in the Road

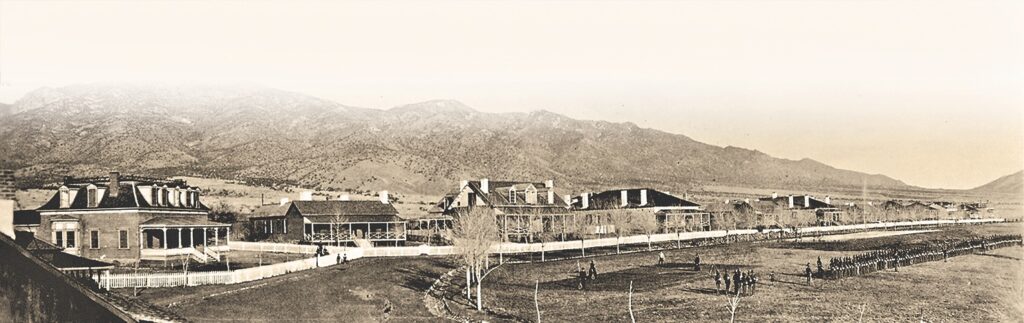

Fort Bayard National Historic Landmark

Established in 1866, Fort Bayard had a long life as a military post in southwestern New Mexico. Built to protect miners in the Piños Altos district, the post remained active until 1900, when the structures were transferred to the surgeon general and became the Army’s first tuberculosis sanitarium. Later, it was a V.A. hospital. Buffalo Soldiers were stationed here, and so was a second lieutenant named John J. Pershing. Now managed by the Fort Bayard Historical Preservation Society, which has a library/archive facility in the nearby Santa Clara Armory Building, the fort offers guided tours 10 a.m.-2 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays, while other tours can be arranged. historicfortbayard.org

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: La Unica Restaurant and Tortilleria, Willcox, AZ; Little Toad Creek Brewery & Distillery, Silver City, NM; The Buckhorn Saloon & Opera House, Pinos Altos, NM; La Posta de Mesilla, Mesilla, NM; Charlie’s Spic and Span, Las Vegas, NM; Oso Grill, Capitan, NM; No Scum Allowed Saloon, White Oaks, NM

Good Lodging: Dos Cabezas Retreat Bed & Breakfast, Willcox, AZ; Murray Hotel, Silver City, NM; Hotel Encanto de Las Cruces, Las Cruces, NM; La Fonda on the Plaza, Santa Fe, NM; Smokey Bear Motel, Capitan, NM