His first trip to California featured an unexpected stop.

December of 1826 should have been a time of triumph for explorer/mountain man Jedediah Smith. He had blazed trails across the West, creating parts of what became the Oregon Trail. The 26-year-old had made his way to California, where he was warmly welcomed at the various Catholic missions. But at the time of Smith’s greatest glory, he found himself stuck.

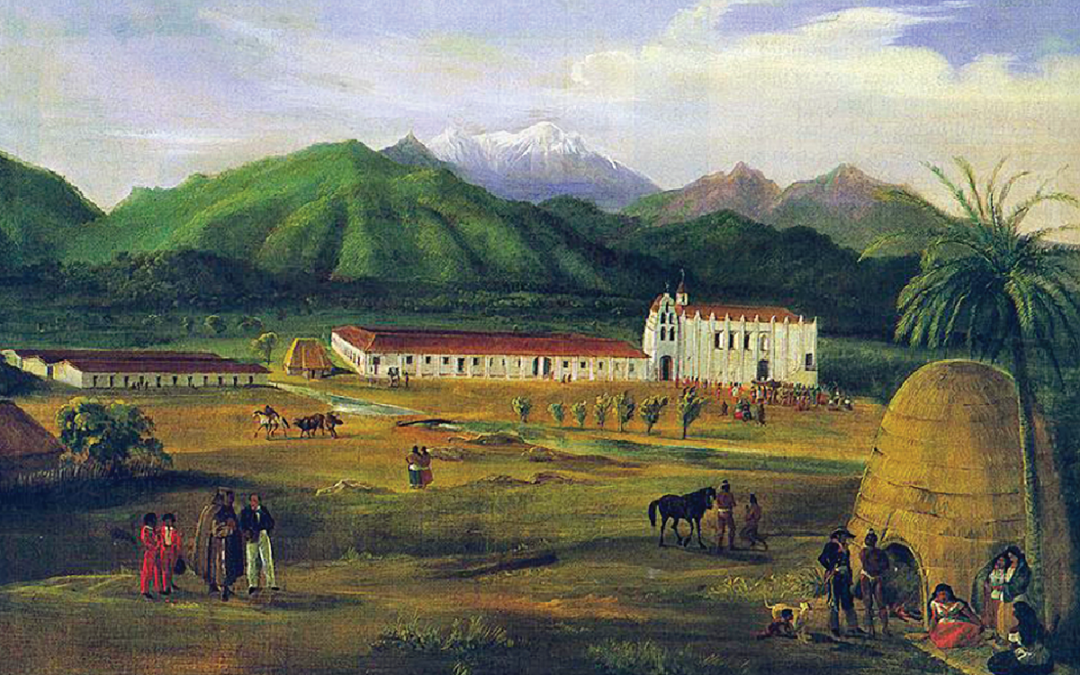

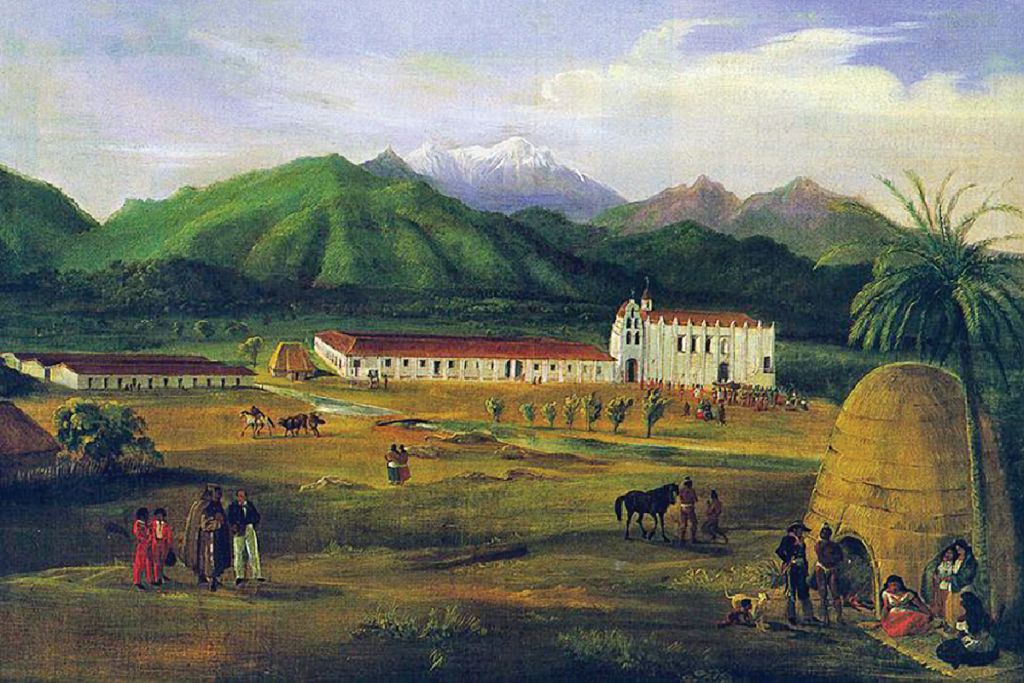

Smith and his 15 men had spent four months traveling from the great Rendezvous in Idaho to the San Gabriel Mission, about 25 miles northeast of present-day Los Angeles. They had gone through parts of Utah and Nevada and become the first U.S. citizens to traverse the Mojave Desert. Despite some hardships on an unknown desert trail, all had gone well.

Until they received an “invitation” from the Mexican Governor of California, José María de Echeandía. Smith and an interpreter were to visit the governor in his San Diego base. Smith could not refuse. So he made the journey—and was placed under house arrest (albeit one of his own choosing).

For a couple of weeks, Smith met with Governor Echeandía and waited for a decision on what came next. He was not exactly impressed with the governor’s decisiveness: “My fate depended on the caprice of a man who appeared not to be certain of any thing or of the course his duty required him to pursue and only governed by the changing whims of the hour.” Indeed, the governor asked for guidance from his superiors in Mexico City, and even considered sending Smith to meet with them. It appears they didn’t know what to do with Smith, either.

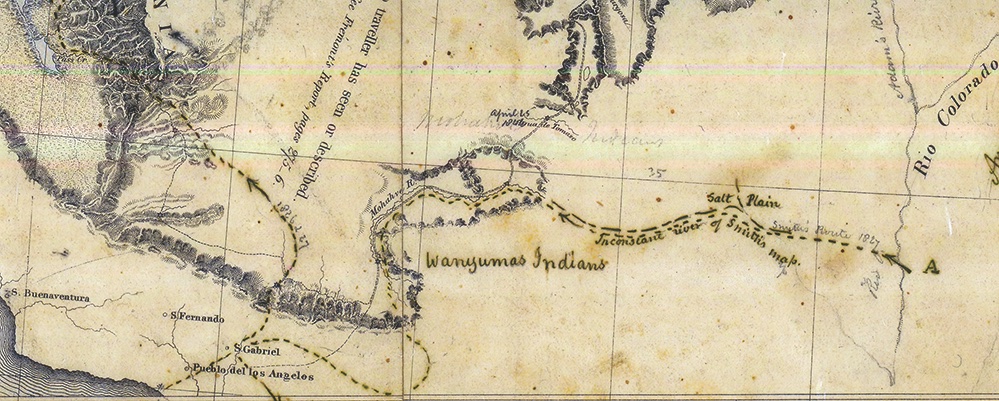

Echeandía requested that Smith turn over his maps and journals; there was concern that the mountain man was a U.S. spy. Smith deftly got out of that by claiming the documents were for his own use only—and that the maps in particular were probably inaccurate.

The governor finally decided to send Smith and his men back the way they’d come. Smith agreed to that…sort of. Once the party got beyond the Mexican settlements, they headed northeast, going through and over the Sierra Nevada, across the Great Basin and on to the Great Salt Lake. Barely surviving their ordeal across the heretofore unknown mountain passes and desert trails, they made their way to the great Rendezvous of Mountain Men, again in Idaho, in July 1827 with stories to tell of their travels.

Smith would later return to California and go farther north to Oregon before being killed by Indians on the Southern Plains en route to New Mexico in 1831. His journals and maps outlived him and were used by countless groups who came after him.