Robert LeRoy Parker—born April 13, 1866, in the small town of Beaver, Utah, to Mormon parents Maximilian and Ann Parker—spent his early years in Circleville, Utah, living with his family in a home that is still standing (and privately owned).

Robert LeRoy Parker—born April 13, 1866, in the small town of Beaver, Utah, to Mormon parents Maximilian and Ann Parker—spent his early years in Circleville, Utah, living with his family in a home that is still standing (and privately owned).

As a teen, Parker worked for rancher Pat Ryan at Hay Springs near Milford and later on the ranch of Jim Marshall near Circleville, where he met Mike Cassidy, the man who influenced his life and led him to eventually assume the alias by which he is most well known: Butch Cassidy.

Both in his youth and later as an adult, Butch Cassidy spent much time in Utah, working for various ranches. After a fight at a dance in Panguitch, he’s said to have eluded law officers by riding through Red Canyon in Bryce National Park along what has now been dubbed “Cassidy Trail.”

Cassidy drifted east to Telluride, Colorado, where the first major crime attributed to him took place when he and companions Tom McCarty and Matt Warner robbed the San Miguel Valley Bank on June 24, 1889, pocketing around $10,500.

Over the next dozen years, he would periodically plunder banks and railroads, employing a hit-and-dodge tactic and working in concert with dozens of outlaws who collectively became known as the Wild Bunch. After robberies, they effectively hid out in remote locations such as Brown’s Park (Colorado), Robbers Roost (Utah) and Hole-in-the-Wall (Wyoming), and by working legitimately for ranchers in those locations or in Wyoming’s Little Snake River Valley.

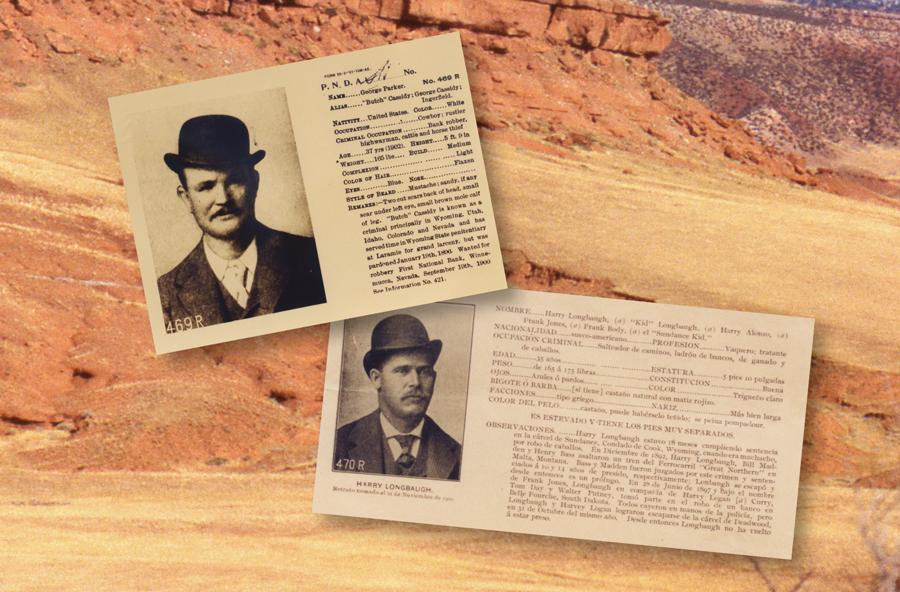

Like others in the Wild Bunch, Cassidy did a stint in prison. His closest associate, Harry Longabaugh, earned his nickname as the result of a jail term served in Sundance, Wyoming. Both served time for horse thievery.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid rode often with Elzy Lay, Matt Warner, Tom McCarty and Flat Nose George Currie; the Wild Bunch may have numbered up to 100 members in a loose confederation of outlaws who seldom bunched together and probably committed far fewer crimes than their record includes. Tracking them across the American West takes you to Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming and Colorado. It’s a long trail, so we’d best get started.

Following Butch

When Butch robbed the Telluride Bank in 1889, he hauled away about $10,500. If he could be there today, he’d need a lot more horses to carry the loot because Telluride is one of Colorado’s wealthiest and most popular tourist destinations. A lot of movie stars have homes nearby or vacation there. Tucked against the San Juan Mountains, the city—a national historic district—hosts a variety of music festivals and attracts skiers to its impressive slopes.

From Telluride, it’s logical to head west into Utah’s outlaw country. I take Route 145 to Placerville and then Route 62 to Ridgway before following U.S. 550 and 50 northwest to Grand Junction, then I-70 and U.S. 191 to Price, Utah, and the nearby small town of Helper—all places Butch often frequented. Just to the west is the impressive Price Canyon, location of Castle Gate, where Butch and the Wild Bunch rode off with more than $7,000 in their April 22, 1897, robbery of the Pleasant Valley Coal Company payroll.

The Western Mining and Railroad Museum in Helper, staffed by a cadre of friendly volunteers and Director SueAnn Martell, has the original steps from the Castle Gate building the Wild Bunch robbed, plus photographs, murals and other information related to the Wild Bunch (mixed in with a display on coal mining and railroad memorabilia).

From Helper, I stay on U.S. 191 to Vernal, another Wild Bunch community. Here’s where the boys reputedly got their moniker when a saloonkeeper noted the “wild bunch” was back in town.

From Vernal, I head east on U.S. 40 into Brown’s Park, a vast region of northwest Colorado that was isolated—and therefore a good place to elude the law—during the era of the Wild Bunch. Not a heck of a lot has changed here. There are still vast distances on roads that have little traffic (to see the heart of Brown’s Park, turn back to the west on Colorado Route 318 at Maybell).

Often after a robbery, Butch and Sundance came here, where they found jobs working for ranchers, living quietly until—or while planning—the next heist. The U.S. 40 route takes you into Craig, Colorado, where a must-see is the Museum of Northwest Colorado, with its outlaw history collection.

I follow Colorado Route 13 north out of Craig to Little Snake River Valley and Baggs, Wyoming, a known hideout for the Wild Bunch, where they holed up in the Gaddis Matthews House (still standing and now a historical landmark).

Continuing north on Route 789, I cross over the Union Pacific Railroad tracks at Creston Junction, Wyoming, and turn east on Interstate 80 traveling to Arlington before I exit the interstate to follow county roads past the point where Butch and the Boys pulled off an explosion and the robbery of the Union Pacific’s Overland Flyer No. 1 train at Wilcox on June 2, 1899, hauling in around $34,000. They dispersed after this event (as they often did). Some rode north to Hole-in-the-Wall, and others headed west or south.

For my part, I continue east to Laramie—site of the Wyoming Territorial Park and the restored prison where Butch spent his two years for horse theft in 1892—now operating as a Wyoming State Historic Site. I depart Laramie by traveling U.S. 30 west to Medicine Bow (always a favorite town to visit because of the small museum and the Virginian Hotel, where you can find a meal, a bed or a shot of Jack Daniels) and then north to Casper via Route 487 and Kaycee via Interstate 25, with its Hoofprints of the Past Museum.

From Kaycee, I head west on Wyoming Route 190 into Hole-in-the-Wall country, a region defined by the red canyon wall with its one tortuous route out to the east, which probably reminded Butch of the canyons in his Utah homeland.

The Wild Bunch routinely hid out here, receiving assistance from local ranchers, and the boys even had a cabin. Hole-in-the-Wall is still pretty remote but beautiful, with its Red Wall stretching for miles in an L-shape. Toward the east, the only one good place to climb out of the area is through the obviously named Hole-in-the-Wall. I’ve never ridden a horse through the opening, but I have hiked it and found it rather treacherous in my rubber-soled Ropers; it would not be my idea of a fun time on a horse with steel shoes. Much of this country is still private ranch land but one good way to visit is by scheduling a trip to Willow Creek Ranch, which operates a ranch recreation business.

From Hole-in-the-Wall, I return to Kaycee and take I-25 north to Buffalo and then Interstate 90 east to Sundance, where the Crook County Museum has a display related to that town’s most famous outlaw connection, including a document chronicling Harry Longabaugh’s stay in the local jail. It was here that Longabaugh earned his nickname: Sundance Kid. He, of course, became Butch’s most loyal companion—the one who stuck by him to the bitter end.

Following the Sundance Kid

Harry Alonzo Longabaugh—born in the spring of 1867 as the youngest of five children in the strongly Baptist family of Josiah and Annie (Place) Longabaugh in Mont Clare, Pennsylvania—left home while still in his teens. He traveled with his cousin to a homestead in Durango and Cortez, Colorado. For the next few years, Harry worked on ranches, including the N-N Ranch near Culbertson, Montana. But on February 27, 1887, when out of work, his life took a twist. Sundance stole a horse, gun and saddle from an employee of the VVV Ranch near Sundance, Wyoming, was arrested in Miles City, Montana, pleaded guilty on August 5 and spent 18 months in the Sundance town jail until Wyoming Gov. Thomas Moonlight pardoned him on February 4, 1889.

After his jail stint, Sundance headed north to work at the Bar U Ranch, a big cattle operation near Calgary, Alberta, Canada (now a National Historic Site of Canada), before returning to Wyoming, where he found ranch work in the Little Snake River Valley. At Little Snake, he developed long-lasting friendships with area residents and some of the outlaws who frequented the Powder Springs hideout to the west—a location Sundance would later use as a safe haven.

Sundance returned to South Dakota’s Black Hills in 1897, getting swept up with Harvey Logan and Walt Punteney following the June 28 holdup at the Butte County Bank in Belle Fourche, South Dakota. The three then were captured in Montana and taken to jail in Deadwood, but they escaped on October 31, 1897, and Sundance quickly hightailed it for the Little Snake River Valley.

Like Sundance himself, I also cut across Wyoming to Casper and then to Rawlins and I-80, where I am ready to head true west once again. The Continental Divide splits here forming the Great Divide Basin. One crossing of the Divide is west of Rawlins at Tipton (exit 158), site of the August 29, 1900, holdup of the Union Pacific Train where Butch and Sundance, anticipating a take of around $100,000, instead got away with a measly $50.40. After the robbery, they rode south over Delaney Rim to the Powder Springs and eventually disappeared into Brown’s Park and Little Snake River Valley.

Traveling through this country today is difficult because there are numerous oilfield roads and it’s fairly easy to get lost. But there are places so remote and rugged, you’ll swear you have time-traveled and might see Butch or Sundance on the skyline just ahead. One way to see the country, and not have such a great chance of taking a wrong turn, is by following the Bitter Creek Road (exit 142). This dirt road runs basically north and south, and will take you through southern Wyoming and into Colorado where you can follow county roads back into Little Snake River Valley or continue southwest through Brown’s Park.

If you stay on I-80 traveling west, exit onto U.S. 30 west of Little America and follow it to Montpelier, Idaho, where the Wild Bunch robbed the bank of $7,000 on August 13, 1896. Following this well-planned attack, the bandits scattered, eventually regrouping in Utah to carry out the Castle Gate robbery, noted earlier.

From Montpelier, I backtrack to I-80 and continue west to Winnemucca, Nevada, where Butch, Sundance and Will Carver robbed the Winnemucca National Bank on September 19, 1900, making away with around $32,640. I’m not interested in robbing the bank in Winnemucca, but it’s worth a long drive just to have a meal at the Winnemucca Hotel. Though not fancy, this establishment serves a mighty fine Basque dinner on Sunday evenings and holidays, and I can easily imagine Butch and Sundance kicking back with a steak and a libation.

One common practice Butch and Sundance employed throughout their lives—and one ascribed to by other men in the Wild Bunch—was to periodically obtain honest work, mainly riding the range and doing other cowboy jobs for ranches from Canada to the Mexican border. Butch and Sundance had learned ranch skills as young men, and that ability to make a hand when necessary served both well throughout their lives, giving them places to hole up when the heat was on.

One positive perk about following the trail of Butch and Sundance is the chance to see some of the rugged lands they routinely negotiated, knowing that much of it is still ranch land or open range where wild horses stand as sentinels to the past.

Candy Moulton hangs her hat near Encampment, Wyoming. She once spent most of a day zigzagging from Tipton to Baggs, Wyoming, trying to follow Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid’s trail, being profoundly grateful to finally make it to Baggs, where she found something to wet her whistle at the Drifter’s Inn, or maybe it was Outlaw Liquor … it was a LONG day.

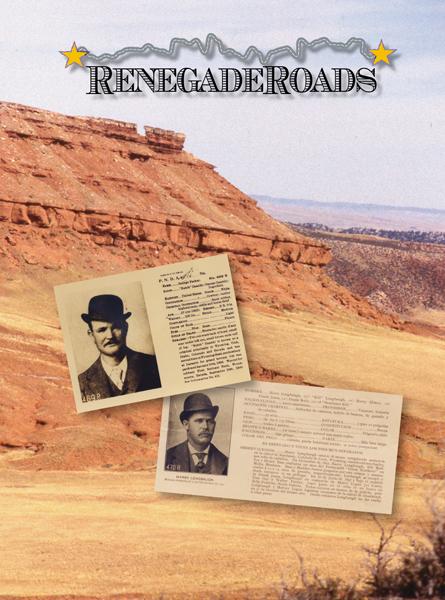

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Candy Moulton unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –