I have a hankering to put some more miles on my car, so I fill my gas tank and head west to visit some of the forts established in the Intermountain West and Northern Plains during the 19th century.

I have a hankering to put some more miles on my car, so I fill my gas tank and head west to visit some of the forts established in the Intermountain West and Northern Plains during the 19th century.

I could follow the dirt roads from my house in Encampment, Wyoming, to Fort Bridger, but in the interest of time, I leave the home ranch to reach Fort Bridger off Interstate 80. Admittedly this is not the way Jim Bridger and Henry Fraeb would

have gone.

Those two mountain trappers started trading with Oregon- and California-bound emigrants at a site near today’s Granger in 1841, but their business enterprise ended that same year when Indians killed Fraeb during a battle along the Little Snake River. Fraeb was shot to pieces and propped up in a manner that made him the “ugliest looking dead man” fellow mountain man Jim Baker said he ever saw.

Bridger may have mourned his partner, but he recognized an opportunity in selling and trading goods to west-bound emigrants. With new partner Louis Vasquez, he started another post on the Black’s Fork of the Green River, where he knew the emigrants would pass. The Bridger-Vasquez trading post was the forerunner to Fort Bridger.

The strategic location served travelers for a decade under Bridger’s management before Mormons out of Salt Lake took control of the post. In 1857, when federal troops under command of Albert Sidney Johnston marched toward Salt Lake City to install a new governor in Utah, the Mormons burned Fort Bridger and retreated to Utah.

Johnston’s army camped in the vicinity of the burned establishment that winter, ultimately rebuilding it as a military post. It was abandoned on May 23, 1878, only to be reestablished in June 1880 after the Meeker Massacre and Ute Uprising in northwest Colorado of the previous September. It then remained active until November 6, 1890.

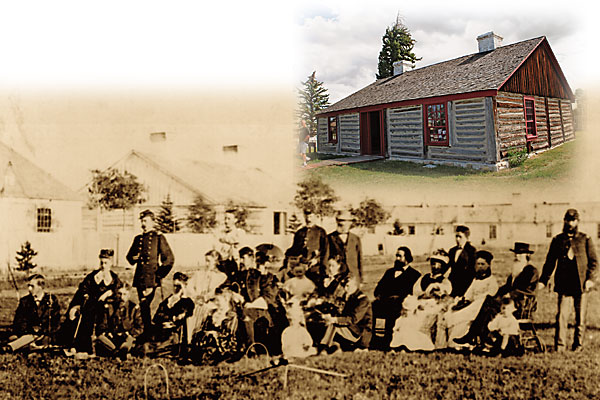

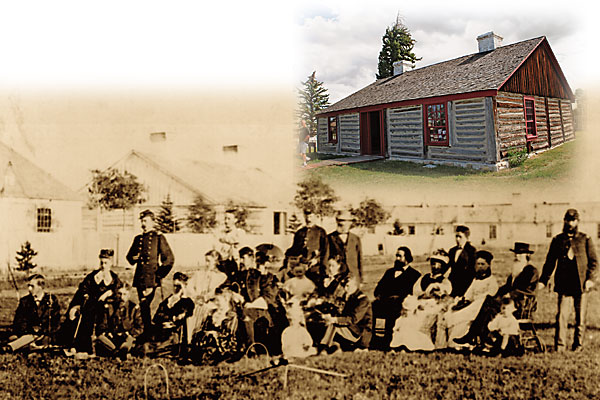

Now a Wyoming State Park, Fort Bridger reflects its use as a frontier emigrant trading post, military post and freighting outpost. Its location on the Lincoln Highway (U.S. 30) even gives it a 20th-century story as the old highway cabins have been restored.

One of the best times to visit Fort Bridger is Labor Day weekend when the annual Fort Bridger Rendezvous takes place with its hundreds of mountain man re-enactors, traders, American Indians and living historians (and tens of thousands of tourists).

For me, the replica of Bridger’s post is my absolute favorite place to purchase shirts. I’d be remiss if I didn’t drop a third of the money I’ll make on this article into the till at the post and walk out with some new duds.

Northwest to Fort Hall

Newly outfitted, I steer the Subaru north and west. Like Fort Bridger, Idaho’s Fort Hall, constructed in 1834, was a fur trade site. Nathaniel Wyeth built it to carve his own business niche into the Rocky Mountain fur trade. He faced stiff competition from Thomas Fitzpatrick, who controlled trade farther east, and the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which started Fort Boise to the west. Although Wyeth’s post was strategically located, he could not hold off the competition and sold out to HBC. Until 1863 the fort continued serving first the fur trade and later wagon train pioneers as they headed west.

The original fort site (now a part of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation) is not accessible to the general public. You will find a replica of Fort Hall in Pocatello, where you can learn about both the fur trade and emigrant history of the 19th-century post.

Onward to Montana

I put a new CD in the car player and let the Metis fiddles lead me north out of Pocatello on my way to Montana and a visit to Fort Missoula, a post settlers called for in 1877 to have military support should the Indian tribes instigate conflict. This, of course, was the period when the Nez Perce tribe refused to go onto the reservation established in Idaho. Instead, under leadership of Chief Joseph and others, they fled east toward Montana’s Bitterroot Valley. The fort construction was barely underway when troops under command of Capt. Charles Rawn received orders to halt the Nez Perce advance. Although Rawn set up a defense in the canyon west of Missoula, the Indians skirted around the troops, giving the canyon site the inglorious name “Fort Fizzle.”

Fort Missoula was home to the 25th Infantry—the black Bicycyle Corps—and later became a military training center during WWI, was the Northwest Regional Headquarters for the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933 and an alien detention center for non-military Italian- and Japanese-Americans during WWII. Much of this history is recounted at the fort’s historical museum.

Next, I head east, following Montana Highway 200 to Great Falls and then Highway 87 to Fort Benton. Its location beside the Missouri River, at the point where thousands of tons of supplies were offloaded for use by trappers, traders, gold seekers, settlers, the military and other territorial residents, makes Fort Benton the most important and one of the most enduring posts on the Northern Plains.

A small section of the blockhouse and wall from the original fort is carefully protected inside the walls of the re-created post. Folks can easily imagine what the fort may have looked like 160 or so years ago. The trading room is fully stocked, and a buffalo press out front reminds us that from 1850-60 the primary trade item here was a buffalo hide.

An annual celebration in Fort Benton, held the last full weekend in June, brings this fort to life. Yet at any season you can stroll along the interpretive trail beside the Missouri River and visit the Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument Interpretive Center to learn more about the river’s role as a commerce route on these Northern Plains. For me a highlight at the interpretive center was seeing a rifle that belonged to Chief Joseph, which was surrendered at the Bear Paw Battlefield in October 1877.

After an excellent dinner and restful night at the Grand Union Hotel, I depart early in the morning, driving northeast on Highway 87 to Fort Assiniboine, just south of Havre. I have a rendezvous of my own with members of the Fort Assiniboine Preservation Association at the H. Earl Clack Museum in Havre in order to actually tour Fort Assiniboine. Though small, the Clack museum, located in the Holiday Village Shopping Center, is a repository about Fort Assiniboine, with its replica diorama and relics from the fort such as bullets, buttons, military insignia and utensils.

The fort, built in 1879 and which had 104 buildings at its peak, is now used by Montana State University as an agricultural research station. The only way to be on the grounds is with one of the regular tours led by the fort’s preservation association.

This pioneer outpost housed 10 companies of infantry and cavalry that were responsible for patrolling the border with Canada, monitoring the activities of Indians who were in the region and stopping bootleggers who operated along the Whoop-Up Trail leading into Canada.

Unlike some frontier posts on the Northern Plains, Fort Assiniboine was built durably with many buildings constructed of locally produced red brick. As an offensive fort built late in the frontier period, it had no stockade, though it was an imposing operation just by virtue of its size, the number of men stationed there and the massive red brick buildings.

North Dakota’s Fort Union

Eastern Montana beckons, and I am on my way along the High Line—Highway 2—en route to Fort Union, just over the border from Montana in North Dakota. Also built beside the Missouri River, at the mouth of the Yellowstone, Fort Union served as the most important fur trade post on the Upper Missouri. Now a wonderfully restored national historic site, the fort livens up with costumed interpreters offering to trade you some goods or demonstrate the lives of their 19th-century counterparts, people like Kenneth McKenzie, a senior partner in the American Fur Company, who had his headquarters here.

After a tour of the bourgeois house and trade room, I’m headed east for a visit to Fort Buford, where Sitting Bull surrendered in 1881, before turning my car south and west along the Yellowstone River. The I-90 takes me near the route of the Bozeman Trail to Sheridan, Wyoming, where I divert to U. S. Highway 87 and follow it along the east flank of the Big Horn Mountains to Fort Phil Kearny, established in 1866 by Henry Carrington as one of three military posts on the Bozeman route.

Along with Fort Reno to the east in Wyoming and Fort C.F. Smith in present-day southern Montana, Fort Kearny was built to protect travelers using the Bozeman road to reach the gold fields in Montana. But it was a short-lived post as attacks by Northern Plains Indians successfully forced the troops to withdraw in 1868. Almost immediately the tribesmen burned the fort. As a result the site offers a re-created post operated as a Wyoming State Park. A good time to visit is during Bozeman Trail Days each June.

My route takes me south on Interstate 25 to Casper, for a quick stop at Fort Caspar, which served to protect travelers on the Oregon and California Trails after 1858.

Then I’m back in the car, traveling south on I-25, where I make a detour at Douglas to Fort Fetterman, which served the military after its construction in 1867. The fort officer’s quarters and an ordnance warehouse are original structures that have been restored. Many other foundations of fort buildings are visible. This fort served as a major supply base for troops involved in fighting with Northern Plains Indians in 1876, including those commanded by Gen. George Crook.

Back on the road, I continue south on I-25 and east on U.S. 26 to the small town of Fort Laramie, which, according to a sign welcoming visitors, is home to “250 people and 6 sore heads.”

Wyoming’s Most Important Fort

I am certain that Fort Laramie, the most important frontier-era military site in Wyoming, is haunted. I say this because in 1999 I had a supernatural experience there. I was traveling with the Mormon Sesquicentennial Wagon Train from Winter Quarters (Omaha, Nebraska) to Utah’s Salt Lake City. I won’t bother you with all the details, but a friendly spirit provided me with some assistance that was gratefully accepted by this weary traveler. I’ve camped at Fort Laramie more than once (always with wagon trains), so I believe that my helper was an overland traveler.

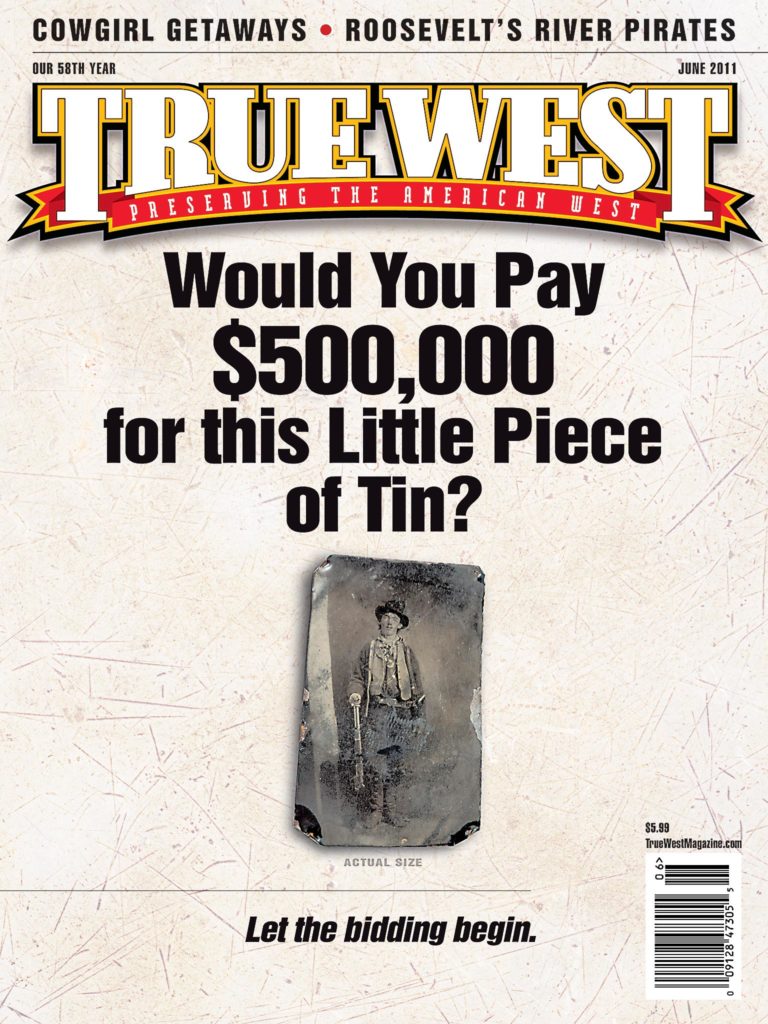

Fort Laramie had its roots in the fur trade (the forerunner site of Fort William was a post established by William Sublette). It was also a treaty site for Northern Plains tribes and the location for distribution of annuity goods. From 1849-90, it served as a military post. A visit gives you a chance to experience all of those stories.

The cast of characters who spent time here is as broad as the West, among them John C. Fremont, Francis Parkman, Calamity Jane, Portugee Phillips, Lakota Chief Red Cloud and hundreds of thousands of overland travelers.

Parkman’s description of a “little fort” built of “bricks dried in the sun…with bastions of clay” does not match what you see on a visit to the site today. But you can walk through Old Bedlam (Wyoming’s oldest extant building), check out the guard house, tour the barracks and cross the parade ground.

Red Cloud signed the 1868 treaty following a conference near Fort Laramie, and his band of Lakotas received their annuities nearby at the first Red Cloud Agency. But by 1873 the agency had relocated to the White River in present-day northeast Nebraska near Camp Robinson, a site that became Fort Robinson. I steer the Subaru that direction by taking U.S. Highway 85 north through Jay Em to Lusk and then U.S. 20 east to Fort Robinson, which is just west of Crawford, Nebraska.

I’ve been here many times; it is one of my favorite forts in the West. That is because of the history—from the Northern Plains Indian War period through the K-9 Corps of WWII—and the fact that it is home to so many original buildings, including some you can actually stay in, such as

the officers’ quarters and enlisted men’s cabins.

If you have a chance to visit with Fort Curator Tom Buecker, you will have met one of the most knowledgeable and helpful curators in the West. He can tell you about the killing of Crazy Horse, which took place on these grounds in 1877, and he can share with you stories of my favorite frontier doctor: Valentine T. McGillycuddy, who served soldiers, civilians and Lakotas during his tenure as an assistant military surgeon here.

Still headed east, I’m off to Fort Kearny, situated south of the Platte River and the town of Kearney. Constructed in 1847, the fort was an important provisioning point for travelers on the trails to Oregon and California. As westbound traveler James A. Pritchard wrote in 1849, “some 80 or 90 Dragoons posted here—also a kind of Post office establishment, which gave us an opportunity of sending back letters.” Today the site is a state park.

An even earlier fort in Nebraska, Fort Atkinson, is named for Col. Henry Atkinson, who brought the 6th Infantry here in 1820 with the Yellowstone Expedition. When Prince Paul Wilhelm, the Duke of Wurttemberg, was here in 1822 he found the fort with “eight loghouses, two on each side. Each house consisted of ten rooms, and was 25 feet wide and 250 feet long.” The only military expedition launched from the fort took place in June 1823 when Col. Henry Leavenworth set forth with the 6th Infantry to aid William Ashley and his party of fur trappers who had a hostile encounter with Arikara Indians at the Indian camp far upstream on the Missouri in present-day South Dakota. The troops from Fort Atkinson also were involved in treaty negotiations with many tribes, including a pact between the Pawnees and the Mexican government in 1824 that led to a truce between those

two nations.

Fort Atkinson was burned by Indians in 1827 after its abandonment by the troops, but the structure has been re-created at the original location and is operated as a state historical park.