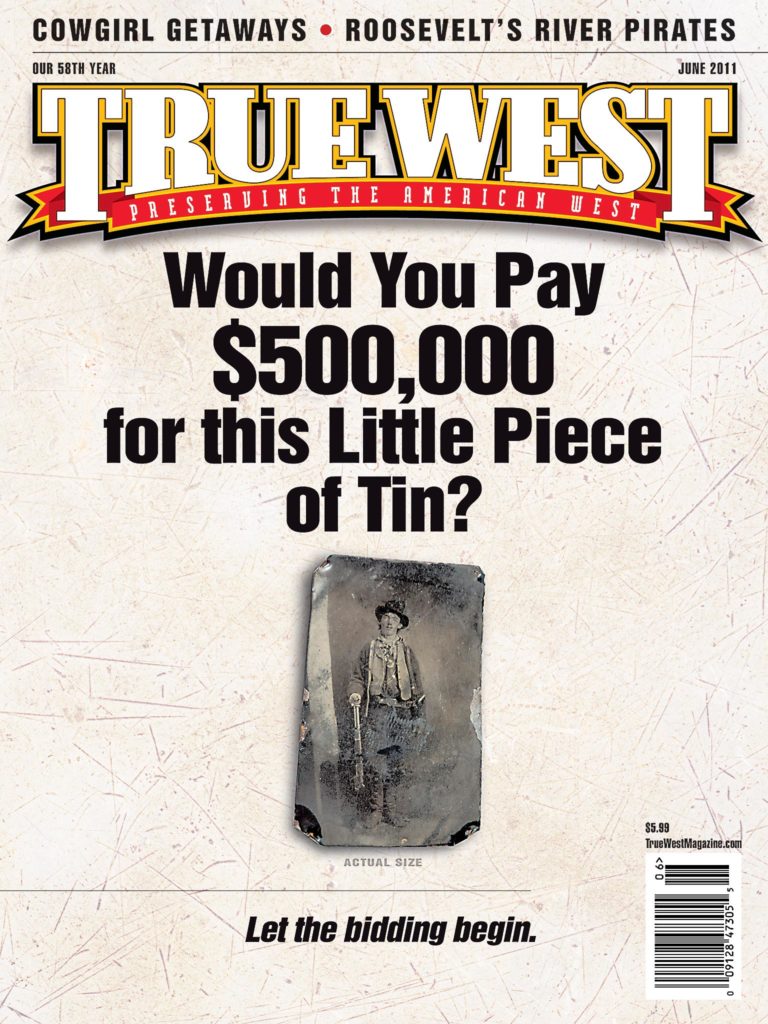

The Billy the Kid tintype is on the auction block, and it might just clear half a million.

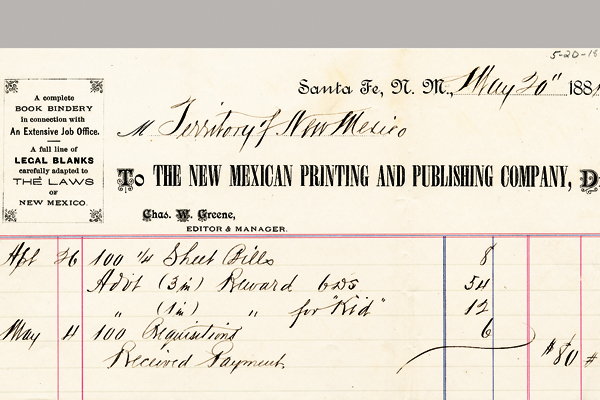

Back in December 1880, New Mexico Territorial Gov. Lew Wallace put a $500 bounty on the head of Billy the Kid.

That was a pretty penny back then, translating to more than $11,000 in today’s money.

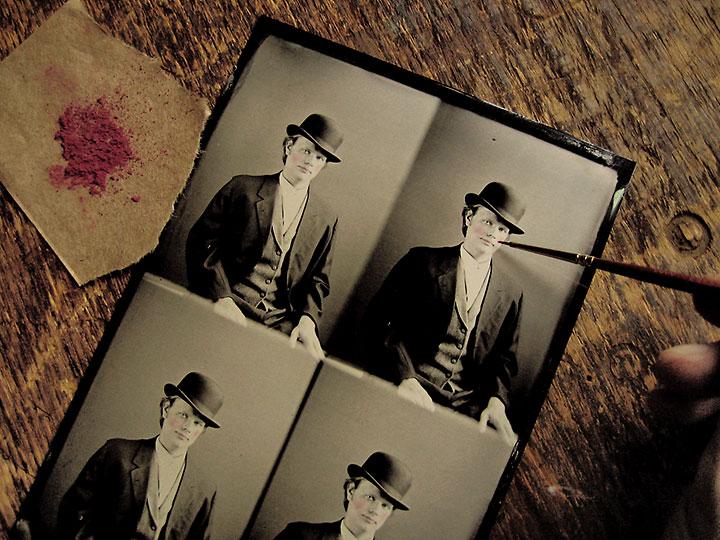

But take that 500 and add three zeroes, and you might have the price tag of the only authenticated photo of the Kid. That’s big bucks, in any time period, all for a cheap, two-by-three-inch piece of iron. With a 132-year-old picture. With damage and wear. And a weird ruffle effect that obscures some of Billy’s body below the waist.

Billy’s gotta be laughing—or crying—that he can’t get his hands on the dough.

Just like the outlaw’s life, a lot of mystery surrounds the tintype. But what we do know is that it was taken in 1879 or 1880. At least four images were made (see p. 28). The Kid gave this one to his rustler buddy Dan Dedrick.

Dedrick, in turn, passed it on to his nephew Frank Upham in 1930. Frank tried to sell it in 1937, but he didn’t get the price he wanted (we don’t know the figure he requested). He eventually gave the plate to his sister-in-law Elizabeth as a wedding present in 1949 (man, where do I get on a registry for a heirloom like that?).

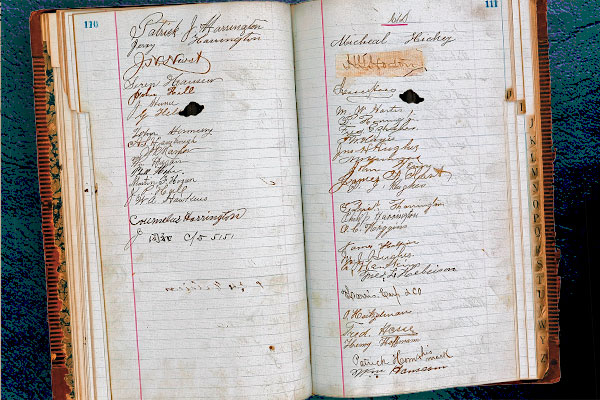

Elizabeth’s sons Art and Stephen ended up with the photo. In 1986, the family loaned it to the Lincoln County Heritage Trust in New Mexico, where the tintype was occasionally shown to visitors (a panel of 18 experts even examined an enlargement of the tintype in 1989, sharing what facts they could discern from the image). The Uphams took back the tintype in 1998.

In 2010, the Upham brothers

began talking to auctioneer Brian Lebel about selling it. Lebel will indeed be putting this rare and famous tintype on the block this June 25 at his Old West Show & Auction in Denver, Colorado.

That’s what we verifiably know about the history of the tintype. We don’t know even more. For example…

When and where was it taken?

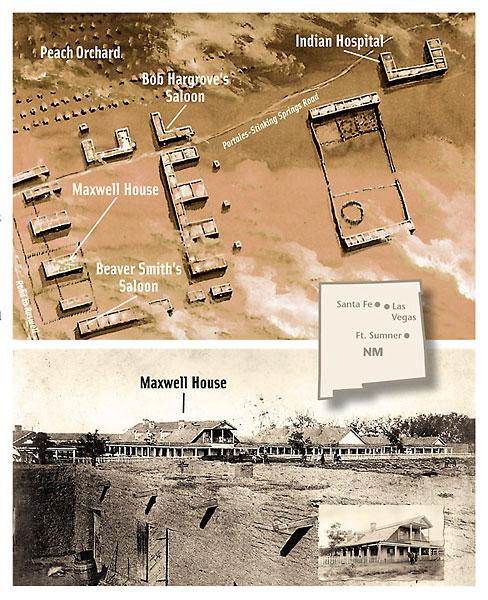

Dan Dedrick told Frank Upham that Billy had the photo taken outside Beaver Smith’s Saloon in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, in 1879 or 1880. (Paulita Maxwell also stated this when she talked to author Walter Noble Burns in the 1920s.) Some experts think a traveling photographer took the shot outside the saloon, while others think the lack of shadow indicates it was taken inside.

Why was it taken?

Not clear. Maybe the Kid wanted to give keepsakes to his girlfriends. Or his pal Dedrick talked him into it, since Dan may have just had his picture taken by the same guy (that tintype will be sold in the same lot). Frank Upham said that Dedrick told him as much. Yet the backdrops of the Billy and the Dan photos are different, leading some to think that this explanation is off-base.

What happened to the other three tintypes?

Here’s where we turn to Old West collector and True West Publisher Emeritus Robert G. McCubbin. He says one went to Deluvina, an Indian friend of Billy’s who worked as a servant for the Maxwell family in Fort Sumner. That one was reportedly lost in a fire in the 1930s.

McCubbin believes a second one went to Paulita Maxwell, one of the Kid’s girlfriends. Billy was gunned down in her brother Pete’s bedroom in 1881. Just what happened to this tintype is not known.

The final copy, McCubbin tells us, may have been given to Celsa Gutierez, another of the Kid’s friends (not a girlfriend). Billy was staying with Celsa and her husband when Sheriff Pat Garrett shot the Kid. Celsa was Garrett’s former sister-in-law. She reportedly gave the sheriff her copy, which he sent to a Chicago publishing house for inclusion in his book The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid. Apparently, somebody there thought the photo was worthless (yikes!) and tossed it.

How did it get damaged?

Most of the damage was normal wear and tear, caused by rough handling over 130-plus years. Some Billy experts believe the ruffle effect probably came from the Kid touching the still-wet photo to the sweater he wore when the picture was taken. Maybe he wiped the tintype off, or he put it in a pocket?

Even beyond the tintype’s cryptic history, this story gets stranger.

Most folks generally concede that the Lincoln County Heritage Trust did not do a good job of preserving the Billy the Kid tintype while it was on loan in its collection. The Billy photo, for sure, was shown under bright lights that, over time, may have caused the varnish to spread over the image.

Somewhere around 1998, rumors began circulating in Kid circles that the famous tintype had been ruined by an overzealous person loosely affiliated with the Trust. He allegedly tried to remove the noise (the markings on the surface of the photograph) in order to see the image of the Kid better. But the rumor is clearly unfounded, because, although dark, the photo still shows the Kid in all his glory.

The Uphams deny the tintype went black, and they repeat it was returned to them under mutual agreement. They say they have done nothing to restore the photo since it came back to them nearly 13 years ago. Photo experts say one cannot bring back a tintype image once it has gone black, yet take a look for yourself: You can still see the Kid.

Another rumor making its way around Billy circles was that a TV crew had damaged the tintype with bright lights in the 1990s. Which TV crew? Nobody knows. What’s important is that it doesn’t matter. Mark Osterman, the photographic process historian at the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film, says there’s pretty much no chance that the temporary span of TV lighting would have damaged the image.

Beverly Hammond, who worked as a historical interpreter for the Trust in those days, has another culprit in mind: the George Eastman House. She claims that this foremost institution in preservation of photographic images damaged the tintype when it was sent to its Rochester, New York, headquarters in the 1980s. When the Eastman House returned the image, Hammond claimed it was “very, very dark. . . . You could see the hat and you could see gun and the boots, but other than that, it was just a blur.” But Eastman House records indicate its technicians merely examined and researched the photo; nobody exposed it to bright lights, chemicals or anything else that might have caused a change in the image.

Bob Hart, who was director of the trust before leaving in 1994, recalls expressing horror when the image was taken out of the climate-controlled safe storage in Rochester and put back on display, where it could, once again, be subject to darkening. (He also confirms that the tintype was a “conditional gift.” When the trust began sinking deeper and deeper into financial distress, he says he alerted Frank Upham to check on its care. “It was just possible that they might try and sell it. And it was, after all, their most valuable item,” he says. The Uphams did eventually repossess the tintype.)

You’ll find no evidence of a “black” tintype in the June auction. The same Billy is shown in a halftone that was published long before all this hoopla with the Uphams began—in 1907, when George B. Anderson featured the tintype in Volume One of his History of New Mexico.

With the Kid’s face peering right back at them, bidders will know what facts to put their money on. Auctioneer Brian Lebel has put the estimate at $300,000 to $400,000, but he concedes the lot could go for much more. Some folks think it could bring up to a million bucks. Whatever the price, Lebel says, and photo authenticators like McCubbin concur, the winner will get the “Holy Grail” of Old West photos, perhaps the most famous tintype in U.S. history: The real Billy the Kid.

Double the Good Times

The Kid likely knew next to nothing about the process used to make his photos, and he probably didn’t care.

One guy who does know and care is Mark Osterman, the process historian at the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York. He not only studies old photos and how they were made, he also uses antique equipment and original formulas to demonstrate the early processes for historians, curators and photograph conservators.

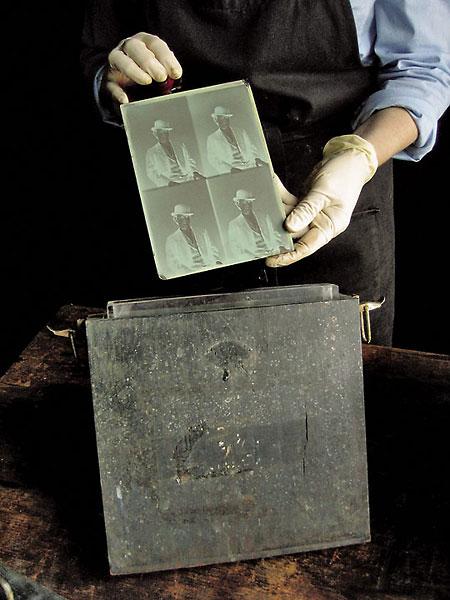

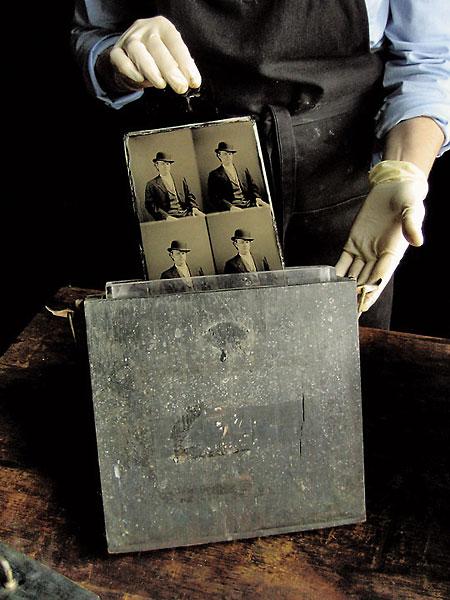

Osterman says that Billy’s photographer used a four lens camera to create a ferrotype, popularly known as a tintype. (Frank Upham, in a 1937 letter, stated six copies existed, but he must not have understood how this camera worked.) This particular style of tintype was called a Bon-Ton, a bastardization of the French term bon temps—meaning “good times,” which referred not only to the fun and games of Parisian life but also to the people who lived them (those folks liked to memorialize themselves through photos). And Billy was nothing if not a good-time kid.

In making a Bon-Ton, a solution of iodized collodion was carefully poured onto a five-by-seven-inch metal plate. The plate was dipped into a solution of silver nitrate to sensitize the collodion coating. When pulled from the silver bath, the plate was placed in the camera. A piece of black cloth covering the lenses was raised for between four and 10 seconds to expose the plate. The exposed plate was then developed with an iron sulfate solution and washed with water. After washing off the developer, the photographer dipped the plate in a solution of potassium cyanide to fix the image and washed it again in fresh water. The plate was then coated with a protective varnish and heated over a lamp.

During the final processing, Billy the Kid may have taken that opportunity for a brief stop at a local watering hole.

When the varnish was hard enough, the tintypist cut the four images apart, placed them in a paper sleeve and handed them over to the customer. Price: Generally a quarter for the four.

Something Mr. Bonney probably never knew—if he’d kept the upper or lower pair together, he could have seen them in 3-D by using a stereoviewer.

That’s double the good times.

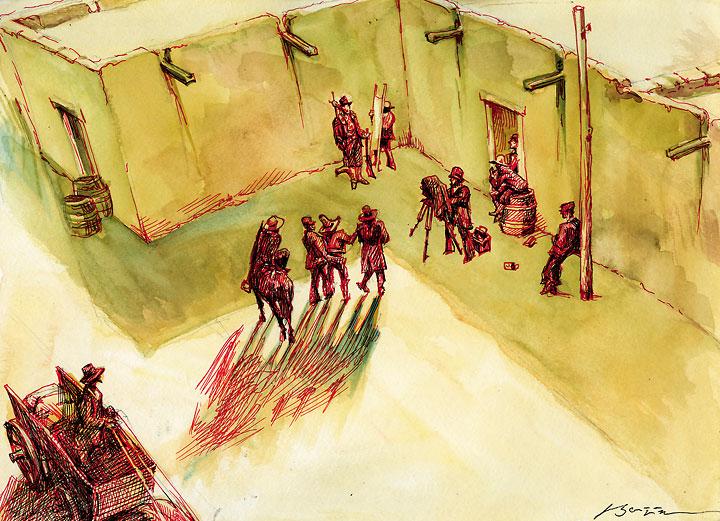

Before the flash

Our photographer (his name is lost to history) possibly hails from Las Vegas, the nearest town with a larger population. He shows up in Fort Sumner in the fall of 1879 or 1880 with a wagonload of equipment. Fort Sumner is barely a settlement, with no church or newspaper.

The crumbling fort buildings are occupied by a variety of ne’er-do-wells who are attempting to carve out businesses in the sparsely settled caprock country. Their landlord, Pete Maxwell, doesn’t even own the land the fort is on. His late father, Lucien, simply bought the buildings. It is a tenuous arrangement in a tenuous locale.

The photographer stops at Beaver Smith’s Saloon (and no doubt at Hargrove’s Saloon as well), asking if anyone wants a photo taken for posterity. Billy the Kid does.

The photographer sets up a makeshift studio outside of Beaver Smith’s Saloon. Before he aims his camera at the Kid, the photographer asks a bystander to hold a white-clothed gurney beside the Kid to bounce any available light up under the Kid’s hat. The Kid’s pals, Dan Dedrick, Tom O. Folliard and Charlie Bowdre, tease and taunt their friend as the photographer takes a six-second exposure.

Some have speculated this photo could not have been taken outside, since it shows no shadows, but that is nonsense. The photographer simply utilized the deep shadow of a wall to place his subject.

After the flash

While the photographer develops the tintype, the Kid may have gone inside Beaver Smith’s Saloon to play some cards.

Photo experts say Billy probably pays a quarter for the four metal images. He puts the four photos in his pocket, probably giving one to his girlfriend Paulita Maxwell, before he rides out to a sheep camp. The Kid moves incessantly, from camp to camp, to avoid capture but comes into Sumner often to dance with the ladies.

The photographer heads off down the road, having no idea he has just taken the most iconic and famous photograph in the history of the West.

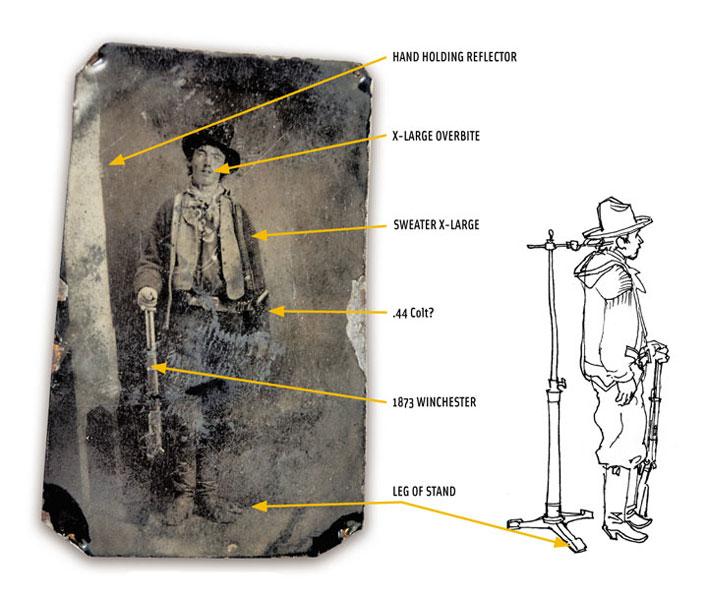

The Photo At a Glance

• His teeth appear to confirm what a contemporary said about him: “He could eat pumpkins through a picket fence.”

• A hand of the photo assistant can be seen holding the light reflector.

• Photo experts think the design on Billy’s bib front shirt is an anchor.

• His sweater is at least two sizes too large. Some see a name tag sewn into the lining with the initials “PM.” Could the Kid have borrowed the sweater from Pete Maxwell?

• Billy wears a gambler’s pinkie ring.

• He carries an 1873 Winchester, which was popular with cow-boys and outlaws because it chambered the same bullets as the .44 Colt, making it easier to carry spare shells.

• Behind Billy’s right foot can be seen the leg of a stand used for stability during long exposures.

• On his head is an inexpensive slouch hat with a side crease.

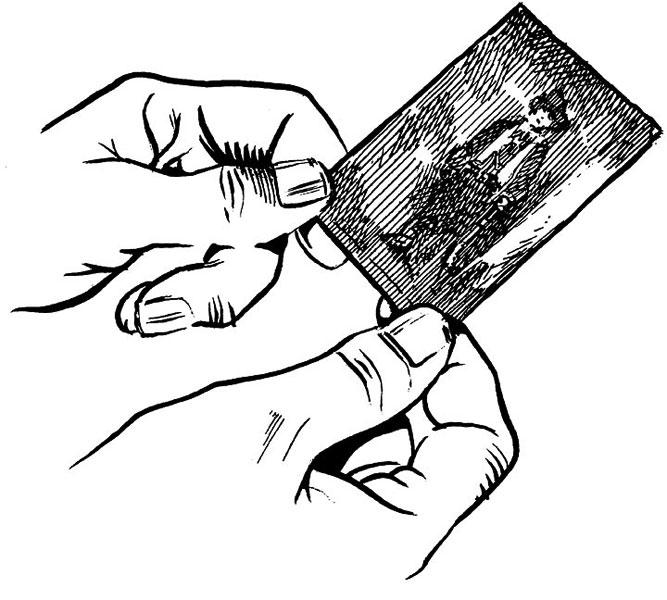

• While developing the wet plate, the photographer handled the bottom corners, leaving his thumbprints. Four exposures were on the ferreotype and the image was reversed as shown (top). This led to the erroneous assumption that Billy the Kid was left handed.

Photo Gallery

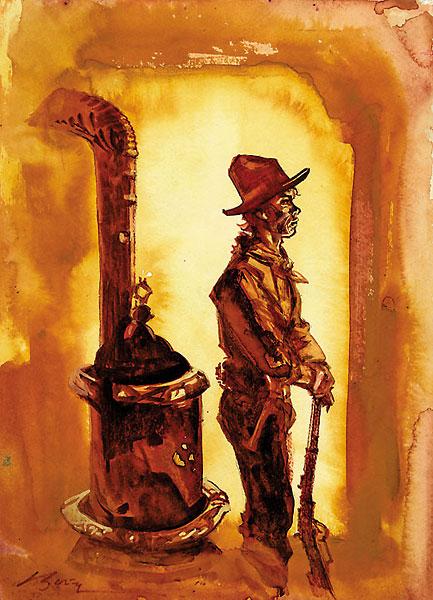

While he’s inside Beaver Smith’s Saloon playing cards, Billy the Kid stands by the stove to warm up.

Brightened and Enlarged to show detail.

Fort Sumner (top) as it probably looked when the Kid had his photo taken. Some historians believe the famous photo of Billy was taken against the wall outside Beaver Smith’s Saloon, similar to the alcove shown in the left foreground above.

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

A lot of folks know this by now, but the Billy the Kid in the tintype is not totally true to life. The shot shows a pistol on his left hip, indicating that he shot southpaw (and thus inspiring the Paul Newman flick The Left-Handed Gun).

But the tintype process spits out images that are mirror images of the subject. That means that Billy’s handgun was on his right side—and he was right handed.

Sorry, Newman.

– Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures –

Sitting for the Bon-Ton tintype at the George Eastman House.

– Bon-Ton Process images courtesy Mark Osterman –