Theodore Roosevelt stood fuming at his Elkhorn Ranch on the west bank of the Little Missouri River in the Badlands of Dakota Territory.

Theodore Roosevelt stood fuming at his Elkhorn Ranch on the west bank of the Little Missouri River in the Badlands of Dakota Territory.

Thieves had stolen the rowboat he used to cross the river to check on his pastured horses and hunt wild game. Roosevelt raced to saddle his trusty steed Manitou, thinking to chase after the desperados and recover his boat. His ranch hands stopped him with logic. It was late March 1886; the river ice had just gone out. Even if he caught up to the thieves, he had no way to reach them through the jammed ice floes along the riverbank. We’ll build you a boat in three days and chase after them, his men told him. That is exactly what they did.

Almost 125 years later, I stood lamenting at the Elkhorn Ranch site on the west bank of the Little Missouri River. My goal had been to canoe a large stretch of the river Roosevelt had taken in his pursuit of the boat thieves. It was Memorial Day weekend; severe thunderstorms and high winds delayed my crew’s expedition, shortening our trip by a day.

After months of planning, my crew and I rendezvoused in Medora, North Dakota: Loren Leichtnam, a backpacking-kayaking compadre from Sheridan, Wyoming; Aaron Bank, gourmet chef and owner of Mr. Delicious Cheesecakes in Bismarck, North Dakota; and his friend, Matt Sehn, construction manager also from Bismarck. Aaron and Matt were old pros at canoeing the Little Missouri River.

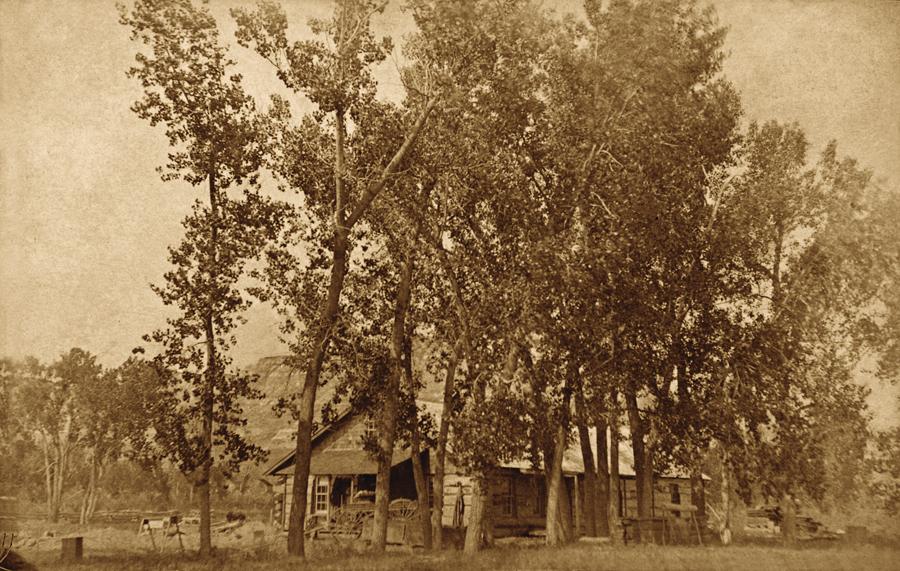

We made the best of the bad weather situation by four-wheel driving over slick, rutted, gloppy roads to Roosevelt’s remote Elkhorn Ranch site, now a small isolated part of the Theodore Roosevelt National Park. The spacious log ranch house and outbuildings are long gone, but the foundation stones remain to mark the location of Roosevelt’s home. Large gnarled Cottonwood trees stand sentinel at the cabin site. The wind creates the same soothing murmur through the same trees Roosevelt had come to love here more than 100 years ago. This land restored the soul of that broken man, whose wife Alice and mother Mittie had both died at his home in New York on Valentine’s Day in 1884.

The boat chase would rouse his inner character, honing the personality of the man who would become one of the most beloved presidents of the United States. Roosevelt would later declare, “…I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota.”

Roosevelt’s Adventure Begins

On June 9, 1884, Roosevelt returned to the Badlands to establish a new ranch where he could experience solitude. He had bought a cattle ranch south of Medora the year before. Rancher Howard Eaton told him to ride along the north-flowing Little Missouri River. Roosevelt would find his solitude 35 miles north of Medora, along the river’s west bank, far from any neighbors. He happened upon the skulls of two elk, their antlers interlocked in death, and he named his new ranch Elkhorn.

Roosevelt employed two Maine backwoodsmen, Bill Sewall and Sewall’s nephew Wilmot Dow, to build his cabin and manage his ranch. Roosevelt brought cattle to the ranch and kept his horse herd on the east side of the river, as the cliffs and breaks formed a natural barrier preventing them from wandering—usually. Most of the year the Little Missouri’s flows were low enough a person could walk across; but during the spring floods, the only way across was by boat, so Roosevelt had one tied to a stout tree.

Farther upriver, in March 1886, three hard cases decided the Badlands were a little too hot for them. Local folks suspected them of cattle rustling and horse thieving, and would just as soon shoot them or string them up. “Redheaded” Mike Finnigan, with his shoulder-length red hair and bushy beard, was the leader of the gang. His peers were “Dutch” Chris Pfaffenbach and Ed Burnstead, whom Roosevelt would call the “half breed.”

Finnigan and friends lived in a shack along the Little Missouri 20 miles upstream from Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch. They shoved their old leaky scow into the river to begin their journey downstream and out of the country. When the three desperados came upon Roosevelt’s fine boat, they took it and headed north downstream, hoping to reach the Missouri River and disappear.

The next morning Roosevelt and his men planned to cross the river to hunt pesky mountain lions that had devoured the deer carcasses they had hanged in a tree for later butchering. Sewall went to the boat to make it ready and found the cut rope and a dropped mitten. He returned to the ranch house and finished his breakfast before saying anything about the missing boat. Upon hearing the news, Roosevelt went ballistic. He had a strong sense of justice. It was just plain wrong for someone to take something that did not belong to him. With no law enforcement nearby, Roosevelt, by virtue of being chairman of the Little Missouri River Stockman’s Association, was determined to bring the culprits to justice.

Roosevelt and his men quickly deduced the thieves had to be Redheaded Finnigan and his gang. No one else had a boat; and the only way to approach Roosevelt’s boat along the shore without being seen would have been by river. Their suspicions grew stronger when the Finnigan crew’s leaky tub was missing from their shack.

Sewall and Dow went about building a boat so they could chase the culprits. To stay out of their way, Roosevelt occupied his time reading Tolstoy’s 900-page Anna Karenina and writing the first chapter in his biography of Thomas Hart Benton. The boat was finished after three days, but frigid temperatures and a blizzard further delayed Roosevelt’s departure.

Six days from the time of the boat theft, Roosevelt, Sewall and Dow set off on their great adventure. Roosevelt sat in the middle of the boat; in the front, Dow paddled as he kept a lookout for ice floes and logs, while Sewall steered from the rear. Once they committed to the river, there was no turning back. The swift current with ice floes jammed along the shorelines, and steep banks of crumbling, slippery mud and sand made it difficult to find access to the shore. No downstream neighbors were around for Roosevelt and his men to pull over for the night and get out of the elements. But Roosevelt had trust in his men. Later he wrote, “They were tough, hardy, resolute fellows, quick as cats, strong as bears, and able to travel like bull moose.”

Following Roosevelt’s Boat

North Dakota’s Badlands are still as sparsely settled as they were in Roosevelt’s day. On our trip down the Little Missouri River, we saw three people—and only after we had entered the Northern Unit of the Theodore Roosevelt National Park. One, a solitary backpacker, had set up his tent on a ridge overlooking the river; the others, two women standing on the bank, shouted to us, “We’ve never seen anyone canoe the river before!”

After a day of waiting out the storm, our expedition was finally on the river. The hot sun warmed my face after days of wind and rain. The air temperature was cool. The river water was opaque, the color of chocolate milk. The riverbanks plunged straight down to the water with few places to put in to shore. When we did land, the sandy, viscous mud sucked our feet down into the muck. One false move, and we could lose shoes.

The wind was a problem for Roosevelt and his men, as it was for us. At times, it would blow from the rear, helping to speed us along; at others, it would swing around and blast us from the front or suddenly switch from one side of the river to the other. Very rarely was there no wind at all. I had to agree with Sewall, who reportedly grumbled, “It is the crookedest wind in Dakota.”

Roosevelt’s posse had provisions for two weeks, but they looked for game along the way. They shot “prairie fowl” and two deer to supplement their food supply, seeing little game as a Gros Ventre hunting party had recently scoured the countryside.

We, on the other hand, saw teeming wildlife. Canada Geese were the most prevalent bird. They didn’t like us on their river and honked loudly as they flew off to land on the water farther downriver. Two bald eagles roosting in a large tree spied us and flapped away. Pelicans flew in formation above us, with one escorting us by swimming parallel to our boat for several hundred yards.

Roosevelt Gets His Men

Three days after Roosevelt’s posse had begun their chase after the river pirates, they spied Roosevelt’s stolen boat, along with another boat, tied to the bank. Smoke rose from a fire off in the sagebrush. Roosevelt and his men quietly moored their boat and crept toward the camp. One man sat near the fire tending it, his weapon on the ground near him. Roosevelt and his men got the drop on him. It was Dutch Chris, and he offered no resistance. He told Roosevelt the others were out hunting.

“The camp was under a lee of a cut bank, behind which we crouched, and, after waiting one hour or over, the men we were after came in,” Roosevelt wrote in his article “Sheriff’s Work on a Ranch” for the May 1888 issue of The Century magazine. “We heard them a long way off and made ready, watching them for some minutes as they walked toward us, their rifles on their shoulders and the sunlight glinting on their steel barrels. When they were within twenty yards or so we straightened up from behind the bank, covering them with our cocked rifles, while I shouted to them to hold up their hands—an order that in such a case, in the West, a man is not apt to disregard if he thinks the giver is in earnest. The half-breed obeyed at once, his knees trembling as if they had been made of whalebone. Finnigan hesitated for a second, his eyes fairly wolfish; then, as I walked up within a few paces, covering the center of his chest so as to avoid overshooting, and repeating the command, he saw he had no show, and, with an oath, let his rifle drop and held his hands up beside his head.”

Most people in that place and time would have hanged these men from the nearest Cottonwood tree, but not Roosevelt. He was bound and determined they should be tried in a court of law. Roosevelt, Sewall and Dow took turns guarding the prisoners. With the temperatures dropping below freezing every night, they could not bind the prisoners’ hands and feet, as they might become frostbitten. Roosevelt made them take off their boots; that way they would not attempt to run off through the prickly cacti.

The next morning they got into the boats and headed down the Little Missouri River, making their way back to Mandan. They battled with ice, traveling only a mile or two a day. The men came upon a massive ice jam blocking the rest of the way down the river. They were quickly devouring the food supply after doubling their number. As they waited for the ice jam to break up, Roosevelt finished Tolstoy’s tome. He asked the thieves if they had any reading material. Finnigan gave Roosevelt his life of Jesse James dime novel to read, which Roosevelt promptly devoured. Close to being out of food, the men had resorted to making unleavened bread by mixing flour with muddy river water.

I must admit we ate better than Roosevelt’s crew did. Aaron is a gourmet chef and owner of Mr. Delicious Cheesecakes—need I say more?

Roosevelt and his men gave up trying to reach Mandan. They decided to march the thieves 50 miles south to Dickinson. Sewall hiked up and out of the river valley to search for a ranch but found none. The next day, Roosevelt and Dow did the same on the opposite side of the river and found a cow camp. The lone cowboy stationed at the camp fed Dow and Roosevelt, and gave them enough coffee, sugar, flour, baking powder and bacon to feed the others. The cowboy told them of a ranch 15 miles to the east where they might be able to get more supplies and transportation.

The next day Roosevelt borrowed a “wiry bronco” from the cowboy and rode to the Diamond C Ranch near the Killdeer Mountains. The rancher agreed to sell him supplies and hired out a team of horses and wagon, with himself as driver. Meanwhile, Sewall and Dow were marching the prisoners toward the Diamond C Ranch. When Roosevelt and the rancher met up with Sewall, Dow and the prisoners, the rancher shook Finnigan’s hand and asked, “Finnigan, you damned thief, what have you been doing now?”

Sewall and Dow returned to the boat. They waited for the ice jam to break before they headed downriver to Mandan, where they would transport the boats by rail back to Medora.

Roosevelt, with the driver and prisoners, took off for Dickinson. Roosevelt did not trust the rancher after discovering he and Finnigan knew each other. For fear Finnigan and friends would try to overpower him, Roosevelt stayed out of the wagon and trudged behind it, with his Winchester resting on his shoulder. The sun thawed the ground, creating ankle deep glop through which Roosevelt slogged. When the men finally reached Dickinson, Roosevelt handed his prisoners over to the sheriff.

Roosevelt headed into town to take care of his blistered raw feet, happening upon Dr. Victor Hugo Stickney. Stickney wrote “You could see he was thrilled by the adventures he had been through” as he was “pleased as punch.” After cleaning off two weeks of Little Missouri mud and dirt, Roosevelt hopped on the next train west to Medora to make the spring meeting of the Little Missouri River Stockman’s Association.

The thieves were tried in Mandan in August 1886. Roosevelt dropped the charges against Dutch Chris, stating that he was “not capable of doing either much good or much harm.” Dutch Chris heartily thanked Roosevelt, who later told Sewall it was the first time he ever had a man thank him for calling him a fool. Finnigan and Burnstead were sentenced to 25 months hard labor in the Dakota Penitentiary in Bismarck.

In 1887, Finnigan wrote a letter to Roosevelt, explaining why they had stolen his boat and stating he and Burnstead were sorry for what they had done. He wrote that Burnstead was in poor mental health and wondered if Roosevelt would intercede for them to leave the penitentiary early. We don’t know if Roosevelt had compassion on the thieves and pled their case, but we do know Finnigan and Burnstead were released from prison five months early.

Most people living in the Badlands thought Roosevelt was crazy for chasing after his stolen boat, and even more so for not taking justice into his own hands and hanging the thieves. But Roosevelt believed in the rule of law, and he lived it.

Roosevelt would later state in a letter to Sen. Albert Fall, “Do you know what chapter…in all my life…looking back over all of it…I would choose to remember; were the alternative forced upon me to recall one portion of it, and to have erased from my memory all other experiences? I would take the memory of my life on the ranch with its experiences close to nature and among the men who lived nearest her.”

Photo Gallery

– Historical photos True West Archives –

– All contemporary photos by Bill Markley –