Civil War doctor loses his family, and his right arm, to a group of psychopaths who have come to rob them, leaving everyone dying or dead. The doc replaces his missing limb with a double-barreled shotgun and goes after them.

Civil War doctor loses his family, and his right arm, to a group of psychopaths who have come to rob them, leaving everyone dying or dead. The doc replaces his missing limb with a double-barreled shotgun and goes after them.

That was the flicker of a movie idea I had in 1993 for a low-budget Western. I needed to flesh it out, but I thought if I pitched the script right, someone might just make it.

That did not happen. Many times.

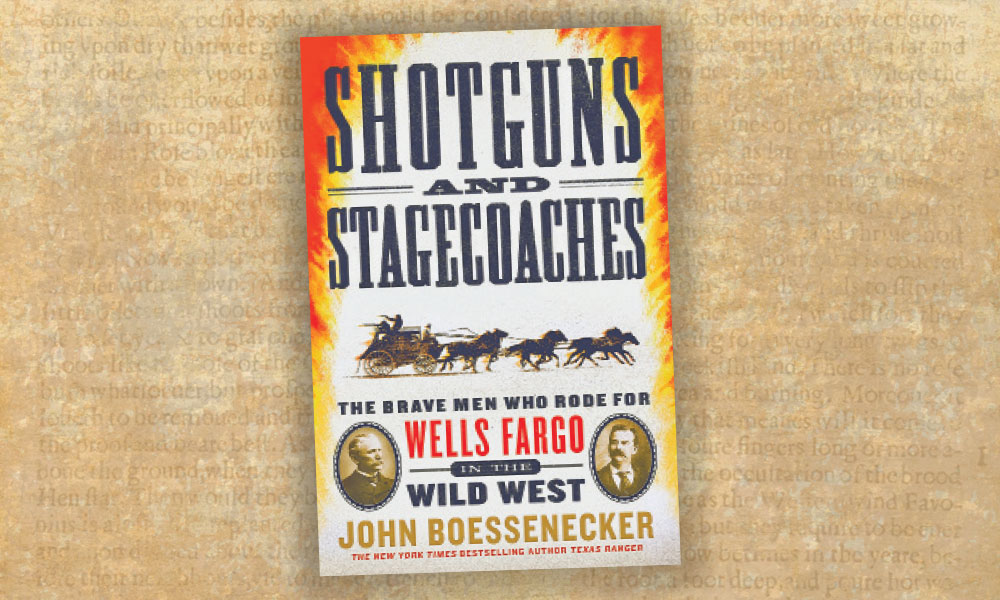

What did happen: This December 3, thanks to editor Gary Goldstein, Pinnacle Books will be releasing Shotgun, a mass-market paperback by a first-time novelist, but not first-time writer.

The process only took 20 years. In the spirit of holiday reflection, when we should all count our blessings, I give thanks to my good friends who helped me in my long journey of getting my first novel into print.

My one-armed avenger first started dogging me while I was driving from California to North Carolina. An amicable divorce had amicably cleaned me out, and I was taking a break from the world of B-movies where I was earning enough to keep the lights on and buy a round of drinks when needed. I was taking a “break,” but not by luxurious choice.

To play off the old saying, I probably could get arrested in Los Angeles, but as far as my screenwriting went, producer interest had waned and so had the enthusiasm of the folks representing me. A lot of freedom can come from having nothing to lose, so why not do what you love?

This was years before HBO’s Deadwood, so when I told my agent about my exciting plan to start a Western, he looked at me like I had shot his dog, then run it over to make sure it was dead. He mumbled, “Good luck,” and I hit the road.

Crossing state lines, with Ennio Morricone blasting, I noodled the script. Deep into Euro-Westerns like 1968’s A Minute to Pray, a Second to Die, and wanting to attempt that tone, I banged out a story treatment on a PC at the public library and faxed it to producers, positive they would think it great.

Responses ran the gamut from a polite, and puzzled, “No,” to an outraged phone message demanding to know why I had sent the crazy thing at all.

Life went on, even if the screenwriting didn’t. A teaching gig fell through, so I became the oldest trainee at a hundred-seat movie theater in Nags Head, North Carolina. As the low-man, my big job was scraping gum off the auditorium seats with a screwdriver, giving me a lot of time to think about shifting writing gears.

My bookshelf, sagging with Westerns, taunted me about Shotgun. I had devoured George Gilman’s “Edge” series and Joe Millard’s “Man with No Name” books, between re-reads of Elmore Leonard. Series titles, movie tie-ins and the classics all got equal quarter. I wanted to attempt something of my own, but I didn’t see my little idea as prose fiction.

Besides, screenwriting is not a great primer for prose fiction. The demands are unique to the form; words have to be spare, descriptions, often clinical, and dialogue, the focus.

A story hangs around your neck just so long before it has to be put down on paper, and I had gone way beyond its time limit. Years passed. I was back in Los Angeles, nailing a few screenwriting gigs, with a job at a video store filling in the gaps. Shotgun kept nagging me. The movie idea was dead, but

I wanted it to exist somewhere.

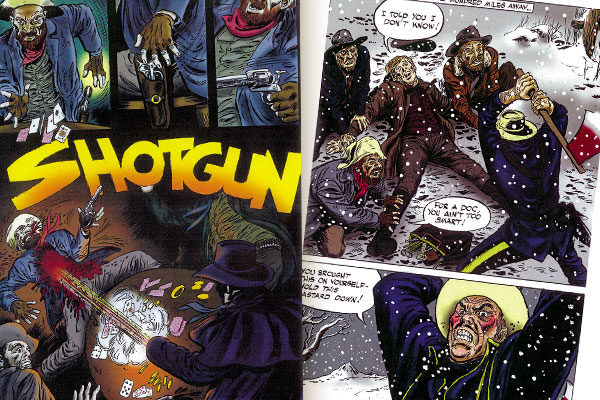

I went for the comics.

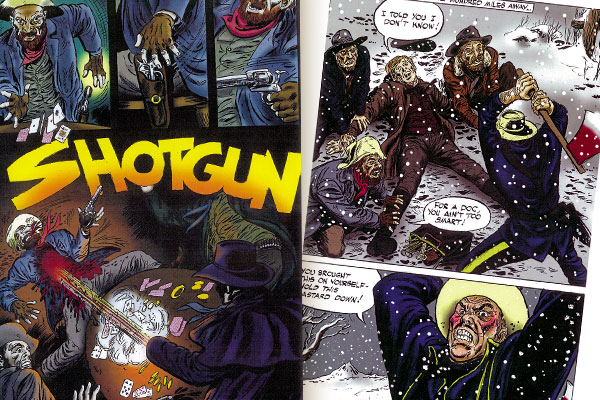

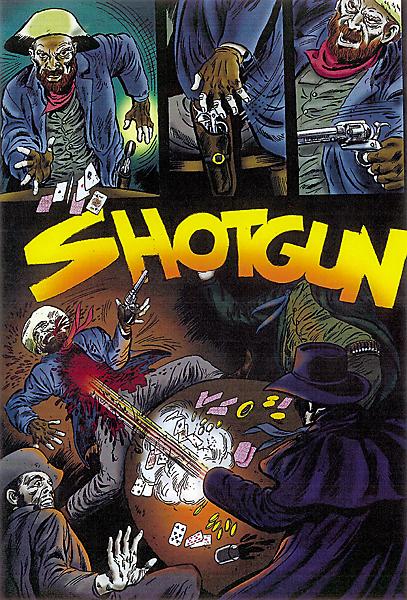

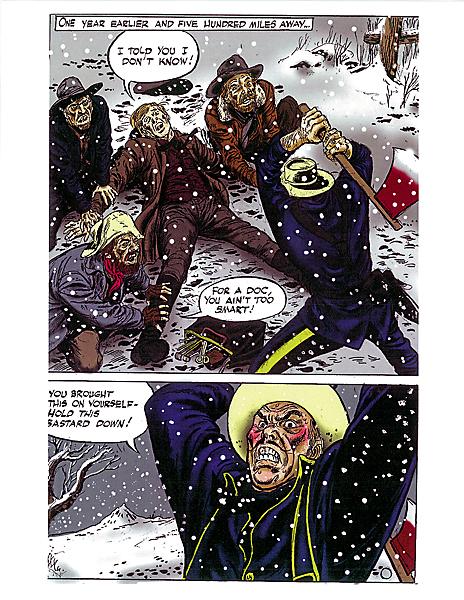

I wrote a comic book script, partnering up with veteran artist Gérald Forton, who drew five great sample pages. Forton had worked for Marvel and DC, and comic publishers loved the project. If we delivered a finished book on spec, which would be hundreds of pages of art, they would put it

out, but wouldn’t commission it. Shotgun faded again.

During this time, I got accepted into the Western Writers of America, because of my movie journalism, and I attended my first convention in Springfield, Missouri.

It was an eye opener. Not only did I meet great writers I had admired for years, but also everyone was amazingly generous with advice, as well as patient with my newbie questions. New friends, who became lifers, and some legends of the genre gave me encouragement and pointed me toward short fiction.

I also met Kensington editor Goldstein for the first time. He knew about my old Horror flicks, and we talked movies and more movies. He opened the door for me to work on a few cinema books, then he asked me about my plans for fiction. Through the efforts of authors Matt Mayo and Larry Sweazy, I had been anthologized a few times and wasn’t quite as unsteady on my feet as I was in the past. Goldstein placed my short story “Two-Bit Kill” in Law of the Gun.

I decided to take a new look at Shotgun. While I reviewed the years of material I had on it, I experienced one of those mental lightning strikes that could be regarded as either crazy or brilliant: this could be the first animated Spaghetti Western!

A lot of work went into that presentation, before it limped, mercifully, into its own grave.

A few conventions later, Goldstein casually asked about fiction, and I sent him every single piece of artwork, the breakdown for every TV episode, an issue of the comic book and the movie treatments for Shotgun. Considering all the reactions I have received for more than two decades, I was stunned when he sent an e-mail stating, “We’re in business.”

You would think with all that preparation, the writing would be a breeze, but I struggled to get to the end. The curve was steep, but with my editor’s patience and the advice of great writer friends, I learned how to shift gears.

Lord only knows what the reaction is going to be when Shotgun comes out in December. I shared this journey not to take bows, nor to marvel at the power of resilience, but rather to show how ideas have a way of sticking with us, of pushing their way through, until they find their own best home. It might happen in a day, or in 20 years, but, when the project reaches fruition, the trip is worth it.

For those who are ready to tackle their first novel, don’t stall. If you have an idea that you believe in so strongly, one that just won’t leave you, then don’t you dare leave it behind. It’s a New Year, and what better way to start it than with “Chapter One?”

C. Courtney Joyner is a screenwriter and director with more than 25 produced movies to his credit. He is the author of The Westerners: Interviews with Actors, Directors and Writers.

Photo Gallery

– All artwork by Gérald Forton –

– Shotgun cover courtesy Pinnacle –