– Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell

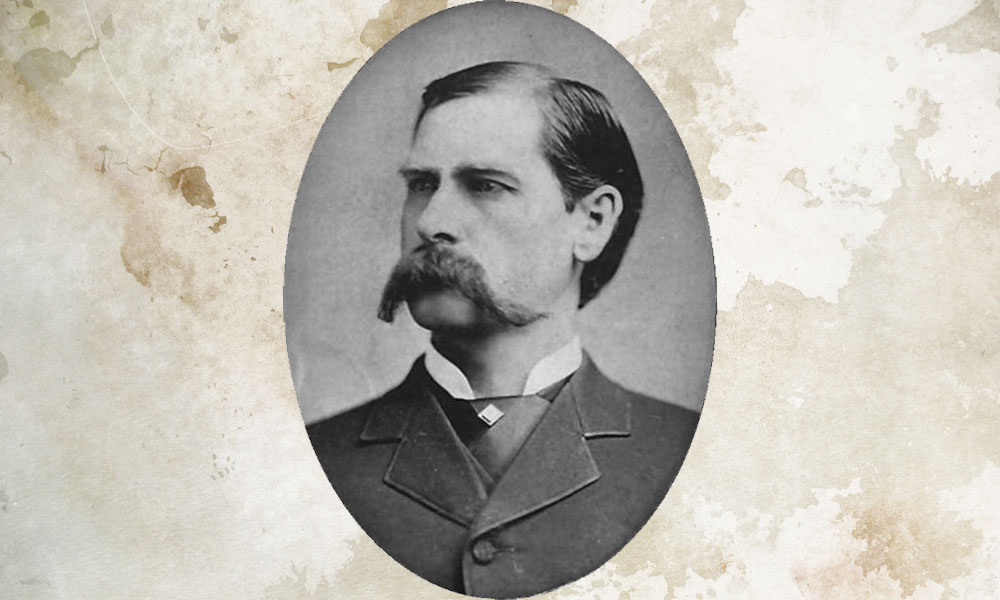

Allen Barra: You have now written two superb, hefty novels involving Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. When did the idea first come to you to write fiction on this subject?

Mary Doria Russell: Like so many, I love Kevin Jarre’s screenplay for Tombstone and was completely charmed by Val Kilmer’s portrayal of Doc Holliday, but I didn’t get interested in the history behind the story until I accepted a position on my town’s planning and zoning commission, helping to draft ordinances for gun shops and…well, tittie bars.

While studying gun control and vice zone laws that had passed Supreme Court challenges, I realized that my little town of South Euclid, Ohio, was dealing with exactly the same legal issues as Western boomtowns like Dodge City, Kansas, and Tombstone, Arizona.

I was struck by the parallels between our time and that of Wyatt and Doc. A recent war had divided the country. Vicious politics and a shamelessly partisan news media. Gang violence along the U.S.-Mexico border. Americans feeling threatened by the Chinese. There’s even a sign being carried in the background of one scene in Tombstone about equal pay for equal work, regardless of sex! I’m consistently drawn to those I feel have been unfairly maligned. Writing about Doc Holliday fits that pattern.

I started reading biographies and decided that poor child deserved better than he got—from movies, from fiction, from history and from life. That led to the novel, Doc, which I thought would stand alone. I figured everybody knew all there was to know about the O.K. Corral. Obviously, I got over that. Epitaph is nearly 600 pages long!

Were there any other people you were drawn to?

Oh, for sure, the McLaury brothers! Their story completely changed my understanding of what happened on October 26, 1881. They were planning on leaving the next day for their sister’s wedding in Iowa. Just knowing details like this led me toward the far more complex situation that I’ve tried to elucidate in Epitaph.

What fiction writers have had the biggest influence on you?

The Scottish historical novelist Dorothy Dunnett taught me to trust the reader’s intelligence and patience. In her Lymond series, she let her main character be described by hostile witnesses, so to speak, and then when she finally let you see that character in private with his guard down, you felt privileged somehow to know him in a way that people in the book didn’t. It’s a neat trick and makes for a strong emotional connection.

I also admire Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies. She redefined Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Anne Boleyn and Thomas Moore by unearthing the real people beneath a mountain of fiction and secondhand history. She works against centuries of presumptions and assumptions, and even though you’re reading a novel, you think, “This is the real story. This is how it must have been.”

And then there’s Stacy Schiff’s biography, Cleopatra. There’s very little directly known about Doc Holliday, but even less about Cleopatra. Schiff shows how a careful biographer can put flesh on bones by understanding the world that surrounded a person and drawing inferences carefully from context.

A lot of fiction has been written about Tombstone and the street fight, some of it by good writers: W.R. Burnett’s Saint Johnson, Loren D. Estleman’s Bloody Season, Paul West’s O.K. and The Last Kind Words Saloon by Larry McMurtry. Even the great Thomas Berger devoted a large chunk of The Return of Little Big Man to Tombstone. But no one has included so many characters from all phases of the story or fleshed them out the way you have.

Yeah, I always swing for the fences. But the other thing is, I wasn’t writing about characters. I was writing about real people who took part in a real event. I wasn’t just using their names. I wanted this account to be definitive and that meant including all those who could shine an interesting light on what happened in Tombstone and why, and what the consequences were.

In Epitaph, you give the gunfight only 42 lines. Given all the moment-by-moment analyses of the shooting, why did you decide against a more detailed account?

I wanted the gunfight to feel as though it were happening in real time. No single participant or witness could see everything as it was taking place, and it was over before anybody realized the full horror of the event. Even in 1881, the post-hoc political spin, ass-covering and legal maneuvering came later, after everyone had time to think, consult with attorneys and plan their responses.

That’s why I decided to see the gunfight itself through Tom McLaury’s eyes. His perception is muddled by a concussion, and he’s watching something unfathomable through a haze of powder smoke. He hardly knows where to look, and then suddenly, he realizes the danger, tries to react and boom! He’s sitting on the ground with a four-inch hole in his chest.

Tom McLaury would never understand what happened during those fatal 30 seconds, or why. He was never going to have the benefit of hindsight because he was going to die in the next few moments. I wanted that immediacy. I wanted you to be in that last moment with Tommy, watching the snowflakes fall, hoping to go to heaven.

What made you give so much space to John Flood, with whom Wyatt worked on his first try at a biography?

Many of us in our 60s are now or recently have been caretakers for the even more elderly. We’ve been up close and personal with the sad realities of failing bodies and minds. Like John Flood, I wanted to see Wyatt and Josie through to the end.

When I started that part of the story, I knew Flood was a mining engineer who tried to help Wyatt write an account of the gunfight, though the result was almost unreadable. I always try to find out about the childhood of any person I’m representing in my fiction and through Facebook, I’ve assembled a volunteer team of “genealogy genies” who track people down for me and follow up on what they find.

Census records told us that John Flood lost his parents and his only sibling when he was quite young. Knowing that he was an orphan helped me understand why he might be willing to help the Earps in their 60s and then remain responsible for them into old age. He wanted family. He wanted to be someone’s son again.

Then one of the genies noticed that in all the census records from 1920 to 1950, John Flood shared a residence with Edgar Beaver. There is a Los Angeles real estate transfer in the 1930s when they bought a house together—and they’re listed as “partners”—and their death records show that they died within months of one another in the mid-1950s.

Not only had we just broken new historical ground, but now I had a genuine love story that could leaven the sadness of the Earps’ final years. John and Edgar were together just as long as Wyatt and Josie were! I was so happy for John that he had someone to stand with him and share the burden as Wyatt weakened and died, and as Josie descended into dementia.

Edgar was a journalist at one point, so his voice could be snarky and cynical, which is fun to work with and kept the final chapters from becoming maudlin. And since John and Edgar died in the mid-1950s, they might well have sat side by side on a sofa, eating popcorn and watching the premiere of The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp on television.

That let me bring the story to a satisfying conclusion that was also living memory for a lot of Boomers. The end really is my favorite part of the book.

Author of acclaimed novels Doc (Random House, 2011) and Epitaph (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2015), Mary Doria Russell holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology; she taught head and neck anatomy at the Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine.