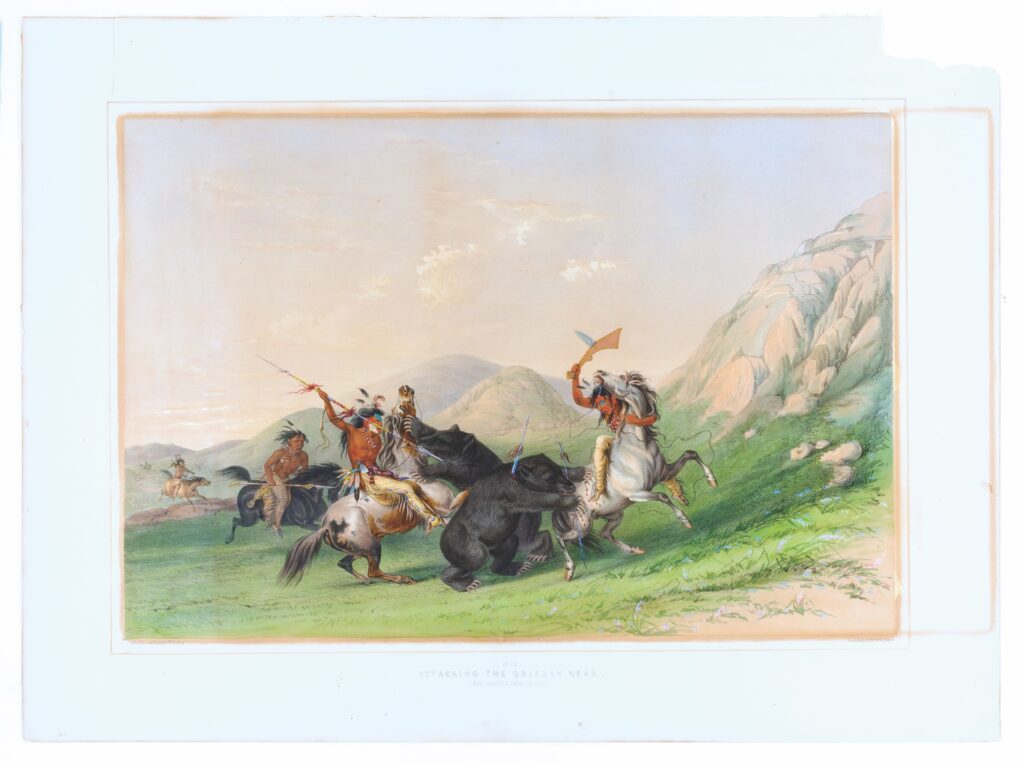

Before the legendary bear was nearly driven to extinction, Ursus horribilis ruled the forests and plains of the Pacific Coast.

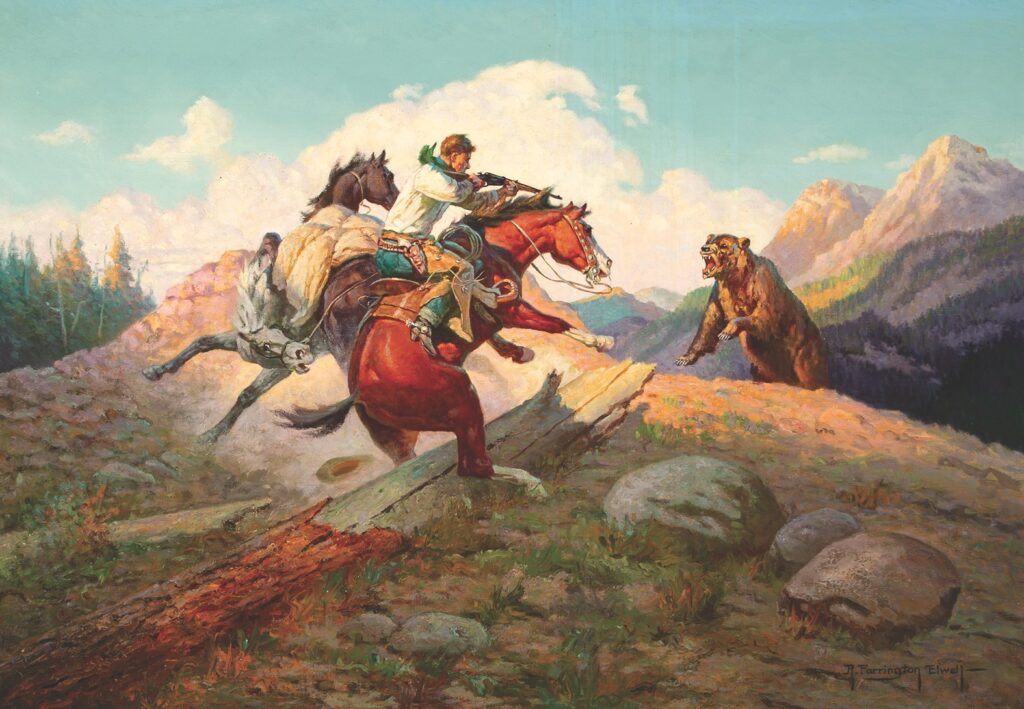

The American Indians who resided in the Mount Shasta region of northern California believed the Great Spirit had created the grizzly bear to serve as master over all other animals. Many a White man who settled on the West Coast of the United States may have been inclined to agree with them when laying eyes on such a large and dangerous mammal. “In attacking a man, he usually rises on his hind-legs, strikes his enemy with one of his powerful fore-paws, and then commences to bite him,” one newspaperman warned in 1863. “His weight and strength are so great that he bears down all opposition before him, and he is very quick. About half a dozen men, on average, are killed yearly in California by grizzly bears, and as many more are cruelly mutilated.”

Grizzly Encounters

While many folks did their best to avoid such a potentially gruesome encounter with Ursus horribilis, some men would achieve a momentary fame by taking on the frontier’s most feared carnivore. Joel Westfall became one of them when hunting a grizzly bear that had recently feasted on one of his prize sows near his home on the Merced River in central California in early January 1861. The vengeful hog farmer grabbed his blankets and weapons before boldly setting up camp near his slain pig’s meaty carcass and awaiting the large predator’s return. Westfall waited long into the night until finally deciding to catch a nap. He was soon awakened by some ominous grunting sounds and quickly spotted a large shadow approaching in the moonlight.

Joel Westfall had barely grasped his rifle before a large grizzly bear was merely 10 feet away. When the bruin suddenly raised its head and began curiously sniffing the air, the hog farmer seized the moment and fired a shot into the animal’s throat. He then dived under his blankets and lay motionless as the slowly dying grizzly tore up the surrounding underbrush in a desperate rage. The bruin finally succumbed to its wound more than 20 minutes later. Westfall breathed a sigh of relief and emerged from beneath his blankets. He was astonished by the dead animal’s girth. “Now if there is any other man in this State, who, ten miles from any accessible human habitation, would camp upon a trail of a grizzly bear going to his midnight repast, and take the desperate chances of a fight with him, we should like to know who he is,” the Costa Contra Gazette declared on January 19, 1861. The reports of Westfall’s successful hunt reached as far as Maryland, Wisconsin, Massachusetts and Georgia.

Benjamin Harrison Baird would not prove as fortunate as Joel Westfall when he encountered a grizzly bear while hunting deer on Grave Creek in Jack-sonville County, Oregon, on October 28, 1864. The 55-year-old farmer was hunting for game that morning when his faithful dog Rover began barking at a female grizzly bear and her two cubs lying on a bed of grass, leaves and moss near the trail. The foolhardy Baird slowly approached the three mammals rather than wisely backing away and took steady aim with his rifle from a distance of 15 yards. Baird quickly realized his mistake after squeezing the trigger and merely wounding the large female. The farmer was soon running for his life as the protective mother chased after him with a vengeance.

The enraged female grizzly caught up with B.H. Baird after chasing him for 200 yards and knocked the rifle from his grasp. The desperate farmer managed to reach a nearby tree when the bruin began fighting with his dog, but only further angered the large bear when, gathering up his rifle, he shot her a second time. When the grizzly charged at Baird with even more ferocity, the farmer sprinted behind a thicket and drew his knife. He later claimed to have stabbed the animal in the belly before getting struck by several vicious blows. The grizzly began mauling the screaming farmer, ripping into his left side with her powerful claws, sinking her teeth into his right side and legs, gouging out his right eye, and biting all the flesh from the right side of his face. The bear then resumed fighting with Baird’s dog Rover and the two snarling animals disappeared down a hillside.

B.H. Baird was remarkably still breathing and managed to reach a cabin over a mile away around ten o’clock that morning. “Mrs. Baird was sent for and hastened with all possible speed the distance of eighteen miles, over a very rough, hilly road, but arrived about five minutes too late to see her husband alive,” the Sacramento Bee later reported. Benjamin Baird had already died from his many wounds around nine o’clock that night, leaving behind his devastated wife, Mary, and their 16 children. His ravaged corpse was then transported back to the family homestead, four miles north of the Rogue River, for burial. Benjamin’s death become a family legend, despite the farmer having crossed the line between bravery and stupidity that fateful morning. In the early 20th century, his remains were eventually moved to the Pioneer Cemetery in Grants Pass.

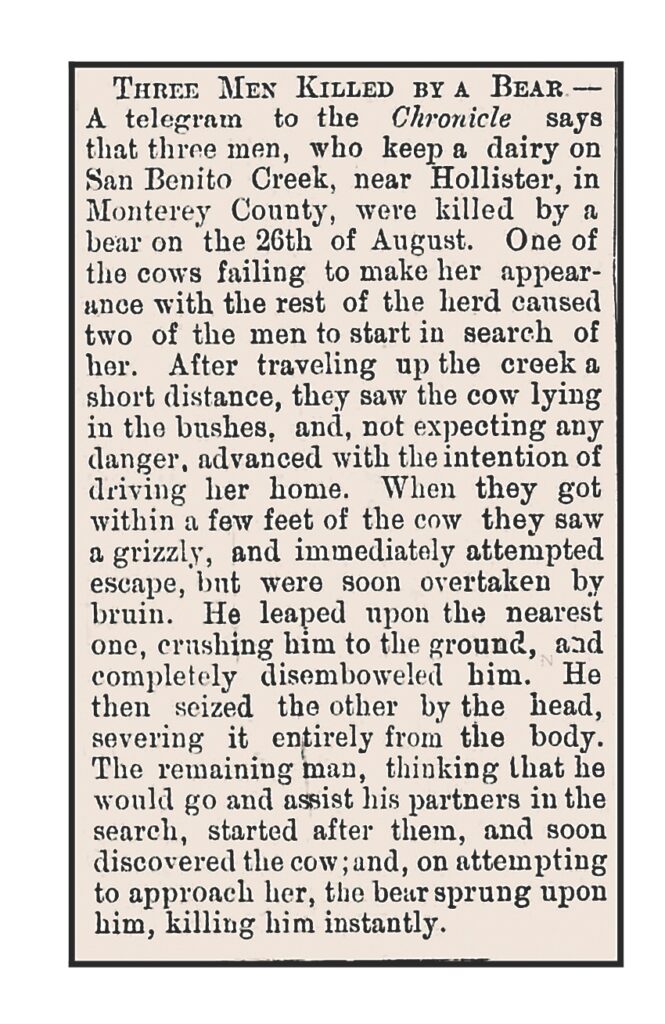

While B.H. Baird had provoked the aggression of a protective mother that morning in Oregon, the most ferocious grizzly bear to ever leave its paw prints in the California soil was probably the beast that killed three cowboys in a single day near the San Benito Ranch on August 18, 1870. The animal’s unique tracks, having lost three of its toes ten years earlier, had long been familiar to those living in the region southeast of San Jose. The horror began after two of the three ill-fated cowboys skipped breakfast to pursue a stray cow that summer morning. They headed up a ravine and dismounted when they spotted the stray lying among the brush. The two cowpunchers had initially believed the cow was sleeping and barely noticed its wounds when a massive grizzly with three missing toes emerged from behind the carcass.

The bear swatted the closest man to the ground in a flash and ripped his abdomen open. The roaring beast then chased down the other cowpuncher, sank its teeth into his skull, and tore the wrangler’s head completely from his body. The decapitated cowboy’s friend managed to drag himself into a nearby brush with his entrails protruding through his blood-soaked shirt. The wounded cowboy then watched helplessly as their cohort arrived from camp a short time later to call them back for breakfast, only to be mauled to death by the particularly aggressive grizzly. The cowhands at the San Benito Ranch eventually realized some of their boys were missing and retrieved the three victims later that morning. The cowboy who had taken refuge in the brush survived long enough to detail what happened, before inevitably succumbing to his wounds later that night. “Three men whose names are unknown, who had been keeping a dairy on the San Benito Ranch, came to their death in a most horrible manner,” the San Francisco Examiner reported.

Grizzly Sports

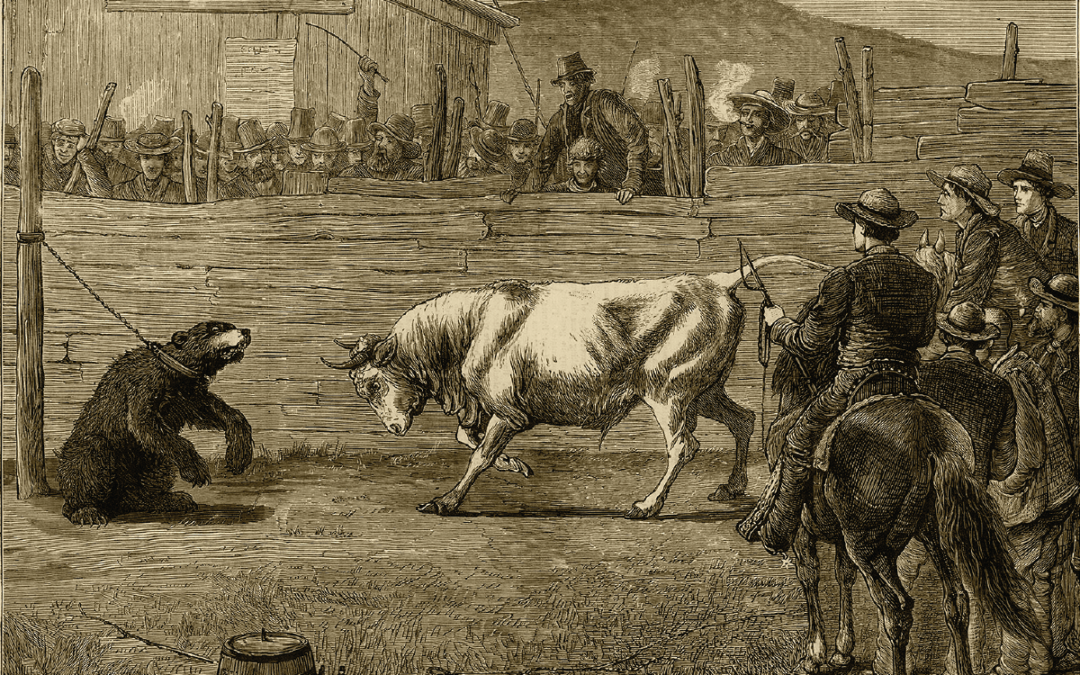

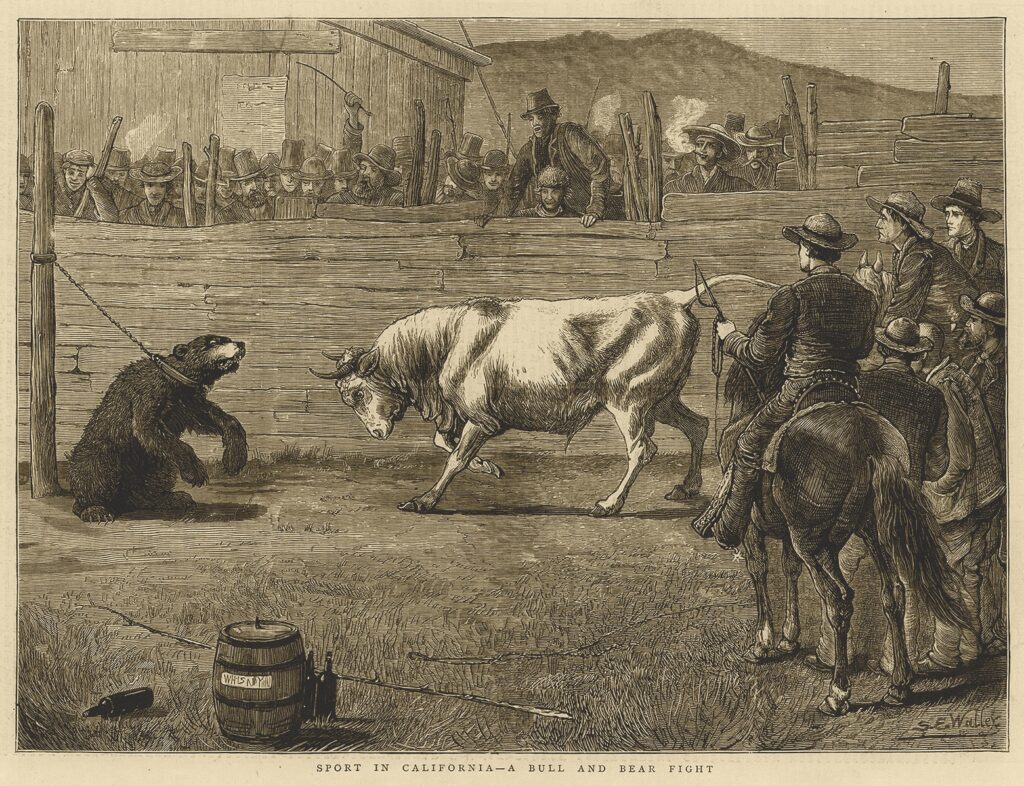

For all the horrors endured by those who were killed by a bear on the frontier, the savagery of man was likewise inflicted upon the grizzlies of California. When bear hunters weren’t killing the animals for the price of their furry pelts, some grizzlies were captured alive and subjected to participating in gladiatorial fights against other fearsome creatures in front of a crowd of onlookers. The Spanish conquistadors had brought the practice of bearbaiting to the Americas many years before, and it remained a popular form of entertainment throughout most of the 19th century in California. The grizzly bears were often chained by their necks to an upright post and forced to fight for their lives against the large bulls or dogs pitted against them inside a “pit” or split-board arena. While many enjoyed the cruel spectacle, not all Californians approved of bearbaiting. The Sacramento Bee condemned the practice as a “barbarous pastime” and a “travesty” on April 9, 1866.

The most famous Californian fighting bear was Grizzly Joe, who was eventually purchased by businessman William Billings and taken on tour to demonstrate his fighting skills before rabid crowds in the Midwest during the 1860s. The celebrated Grizzly Joe had vanquished bulls in Omaha, Nebraska, and St. Joseph, Missouri, before his most publicized “prize fight” against a bull named Texas Johnny took place in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 25, 1867. A pretentious reporter from the Daily Missouri Republican was among the estimated 2,000 people in attendance at the Abbey Track that Christmas afternoon and covered the event and every “round” as if it were the fight of the century:

There was a fight between a bull and a bear; that was enough to set St. Louis agog…Near the judges’ stand stood Texas Johnny, rearing his head like a fiery steed, but evidently aware that a stout rope, attached to his right hind leg was a formidable barrier to much locomotion, until a signal from the drum said a “little more slack.” Grizzly Joe was alike an object of great curiosity and no little anxiety among the betting gents, as to how he would come out; whether or not the bear would take too many horns and get “groggy,” or the bull be unable to bear it out. Joe looked as though he was master of the situation as he complacently peeped through the bars of his cage and stretched out a paw, eager for the attack. Three stalwart men had been previously appointed to see fair play and hold the ropes that kept Joe and Johnny Bull in sage limits from the surveying crowd, the aforesaid referees, though everybody wanted to be “boss,” being also provided with sharp sticks to goad the animals, when necessary, into a frenzy of passion…at precisely half-past 3 o’clock P.M., the band struck up Yankee-doodle and bruin was let out, a moment of suspense to the gaping multitude.

Texas Johnny was declared the winner following the ninth and final “round” that evening. “The bear declined to fight,” the Burlington Free Press lamented. “Once he made a frantic rush for a small building just outside the fence and succeeded in climbing through the window in his fright but was speedily hauled back by the rope.” The fighting grizzly had retreated to his cage the moment “the managers of the moral entertainment opened the door.” Grizzly Joe had suffered enough wounds during his vicious exchanges with the Texas Longhorn that his scheduled fight against two bulldogs in Chicago, the following month had to be postponed. His owner William Billings was also failing to turn a profit. “Grizzly Joe, the fighting bear of St. Louis, has eaten his owner bankrupt,” the Greenville Advocate declared on January 9, 1868. “An attachment was served on the latter a few days ago for a debt of $56, the greater part of the debt for boarding Joe.”

Grizzly Joe had participated in his last “prize fight” that evening in St. Louis, Missouri. William Billings promptly sold the “nine-hundred pound” animal to W.B. Gall of Ohio shortly after. “Yesterday there arrived in our city the great prize-fighting bear,” announced the Cincinnati Times on March 24, 1868. W.B. Gall saw that the bear he had purchased was “turned over to his new quarters, in the vicinity of Brighton, where he will be carefully cared for.” Those opposed to animal cruelty in frontier times hoped the famous Grizzly Joe would enjoy his retirement and a peaceful death in the Buckeye State.