They’ve been dismissed as “just waitresses,” suggesting they weren’t at all important in the history of the Old West.

They’ve been dismissed as “just waitresses,” suggesting they weren’t at all important in the history of the Old West.

But that ignores what the Harvey Girls meant to the settlement of this new frontier. “The Harvey Girls were just waitresses. Their counterparts were just cowboys; just miners with nothing to call their own but a mule and a pick; just trappers without families or homes,” writes Lesley Poling-Kempes, author of The Harvey Girls.

Most know of these women only because Judy Garland starred in the 1946 movie about them. Judy wore the right outfit—the heavily starched, ironed and immaculate white apron over a plain black dress, black stockings and sensible shoes—and sang her heart out in the Academy Award-winning ditty by Johnnie Mercer, “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe.”

What many don’t realize, though, is that the Harvey Girls provided more than just a trusted and needed service to the railroad-traveling public.

Not Liquored Up

Fred Harvey was the kind of immigrant who made America what it is today—inventive, determined, shrewd, strict.

At 15, the English lad came to New York City and earned two dollars a week as a busboy, picking up the inner workings of the restaurant business. He later became a mail clerk on the railroad and saw firsthand the dismal dining options for travelers. Railroads relied on private firms along the way that invariably served bad food and lousy service at ridiculous prices.

Fred was sure of a better way—that clean, well-organized restaurants with good food and efficient service would lure travelers. His business plan impressed the owners of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, and their partnership is the stuff of American business legend.

The first Harvey House opened in 1876 in Topeka, Kansas, but quickly expanded to California. From restaurants, Fred went on to create some of the grand hotels of the Southwest. This company let no grass grow under its wheels. In 1883 alone, Fred opened seven dining rooms and five hotels. At the height of his empire, 23 hotels and 54 dining rooms carried the name of Harvey House.

At first, he hired men to serve as waiters. But after firing some for a midnight brawl in New Mexico in 1883, he followed his manager’s advice to hire women because they’d be less likely “to get liquored up.”

He knew he’d have to import women, since few lived in the West. He placed ads in Eastern and Midwestern newspapers for “young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent.” Although the ads didn’t specify, he meant white women of good character. Fred never hired blacks and seldom hired hispanics or Indians to be his Harvey Girls.

Fred knew he had a hard sell to overcome the stigma of women working outside the home, but he felt confident he could turn things around and make waitressing a respected profession.

Did the Harvey Girls help change people’s minds? Poling-Kempes, whose 1989 book called them the “Women who Opened the West,” thinks so. Writers at the turn of the 20th century also saw their influence, including one reporter who wrote in the Leavenworth Times in 1905, “The girls at a Fred Harvey place never look dowdy, frowsy, tired, slipshod or overworked. They are expecting you—clean collars, clean aprons, hands and faces washed, nails manicured—there they are, bright fresh healthy and expectant.”

The National Fred Harvey Museum, being created in Leavenworth, Kansas, certainly thinks so. “The Harvey Girls became perhaps, the most lasting legacy of the Fred Harvey story,” states the museum’s website.

In a telephone interview from her home near Abiquiu, New Mexico, Poling-Kempes says she got interested in the Harvey Girls while working on a documentary about Fred Harvey. “We asked for people who’d worked for Fred Harvey and got a lot of letters from women who’d been Harvey Girls.”

One of the surprises she found is that there were so many Harvey Girls. From 1883 until the late 1950s, when train travel lost out to the private automobile and airlines, and most Harvey Houses closed, some 100,000 young women had signed contracts to become Harvey Girls. “What most impressed me was what a grand family they were part of. Some stayed six months; some stayed 40 years.” She estimates about half of them remained in the Southwest after their contracts were up, marrying and helping populate the new land.

The girls who answered Fred’s ads were motivated by three factors: economic necessity, the lure that the West was full of single men and a chance for independence. Poling-Kempes found that fully half of them were “daughters of American pioneers” from rural areas and almost all came from farms or small towns.

Long Hours and Exacting Standards

Harvey Girls often worked 12-hour days—usually split shifts scheduled around train schedules—six or seven days a week. Their pay was room and board, all travel expenses and $25 a month plus tips, which was a fairly generous salary. By all accounts, Fred treated his employees well.

While they were Harvey Girls—they signed six-month or year-long contracts—they were required to maintain the highest standards. They lived in a Harvey House dormitory that forbade men and had a strict curfew. They weren’t supposed to date other employees, although that rule was often broken, and they couldn’t marry during their contract. On the job, everything from their uniform to their hair to the ban on makeup was the same in every Harvey House. “Harvey must have been acutely aware of the opportunity for public criticism of single women away from home, and so he dressed the Harvey Girls in outfits befitting a nun,” Poling-Kempes writes. Skirt hems were exactly eight inches from the floor, and outfits first designed in 1883 changed hardly at all over the next 50 years.

But the girls weren’t the only ones subjected to Fred’s exacting nature. His system of notification of diner’s wants, his rules for service, the quality of food, the way it was presented and the decorum in his restaurants and hotels were all dictated by the “Harvey standard.”

In an agreement with the railroad, porters took travelers’ orders as the train approached, then wired them ahead so the meals could be prepared. As the train stopped, a large bell rang over the front door of the Harvey House to announce the travelers and led them to the dining room. Hot food was ready, and diners enjoyed a meal in the 30-minute layover.

To meet that limited timetable, every-thing had to be thought out. A coffee cup demonstrates that story.

Every Harvey Girl knew the “cup code” that helped provide efficient service, so as the first girl took the order, the second girl could serve the refreshments. If the cup handle was pointed towards six o’clock, the customer wanted coffee; the handle at high noon meant black tea; a handle at three o’clock, green tea; a handle at six o’clock, orange pekoe; and if the cup was removed, the customer wanted milk.

All this was learned in a rigorous training program conducted in Kansas City before girls took the Santa Fe Railway to their posts.

This attention to detail—and demand for first-class service—was a major boon to tourism of the West. “Good service at a good value tempted countless thousands of visitors to head west, knowing that the Fred Harvey Company would take care of them along the way,” reported the public TV series “Arizona Collection.”

The Southwest was a largely unknown desert wilderness before Fred teamed up with the Santa Fe Railway. But, as Poling-Kempes writes, Fred, the railroad and the “thousands of women known as Harvey Girls accelerated a change in eastern and Midwestern attitudes toward the areas known today as the states of Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and California.”

Today, these early women of rail-roading who greatly contributed to the settling of our West are remembered by the Harvey Girl Historical Society, which has a branch at the Orange Empire Railway Museum in Perris, California.

Photo Gallery

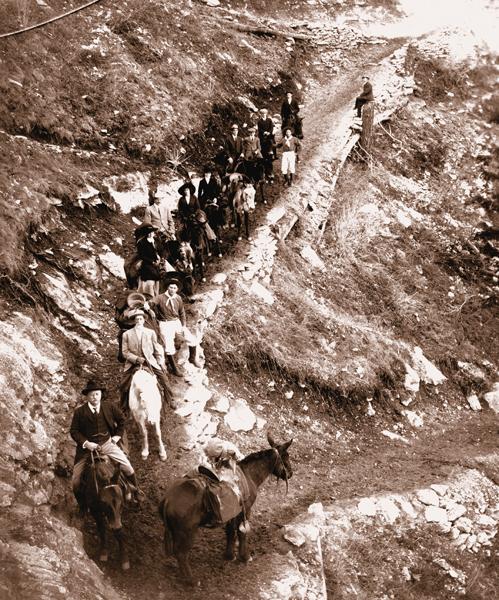

– Courtesy Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection –

– Courtesy Grand Canyon National Park Museum Collection –