One was the “man who stopped time.” The other was the man who drove the golden spike.

One was the “man who stopped time.” The other was the man who drove the golden spike.

Photographer Eadweard Muybridge invented stop-action photography and, later, motion pictures. Leland Stanford, railroad magnate and founder of the university that bears his son’s name, was the wealthiest man west of the Mississippi.

Their friendship, and Stanford’s patronage of Muybridge, engendered what may have become the greatest contributions the West has made to the world: projection, moving imagery, screen imagery—basically the media most of us consume today more than any other.

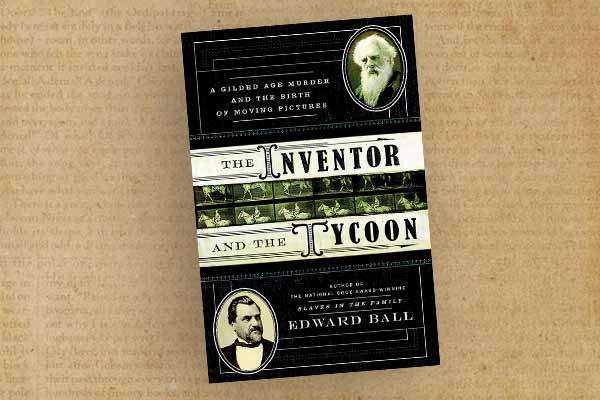

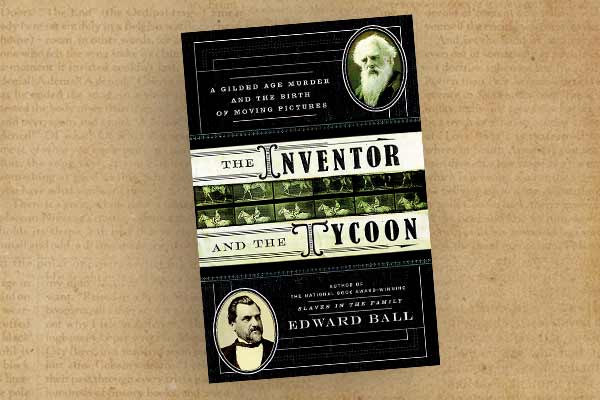

In The Inventor and the Tycoon, National Book Award-winner Edward Ball traces a partnership between two men whom history has neglected, unjustly.

Stanford and Muybridge came to California separately—each man alone and essentially prospectless—in Gold Rush days. Each attained success independent of the other. The unstable Muybridge is revealed as a man who restlessly, relentlessly re-invented himself, all his life long. Stanford is taciturn, unreflective, boorish. The untutored Muybridge—artist, scientist, genius, fool, murderer, lost soul, driven eccentric, world changer—is as compelling, and exasperating, a figure as a Rousseau or a Van Gogh.

Author Ball knows his material and serves it up laced with irony and displaying considerable narrative talent. The Westernness of the tale unfolds in indirect fashion. Muybridge chases art and culture, while the Wild West erupts all around. California’s homicide rate in 1854 (540 killings) was, for its population, “100 times” that of today. Rogues abound. Just down the street from Muybridge’s home, gangster Charles Cora guns down U.S. Marshal William Richardson in 1855, in daylight. He’s jailed. A city official, James Casey, enraged at a fiery newspaper editor—the self-styled “James King of William”—guns King down on the street. He’s jailed. The latter killing triggers the formation of a Vigilance Committee (initially 2,500 strong!) that declares war on random violence—but not before it lynches Cora and Casey.

Muybridge, fresh to these parts from England, capitalizes on King’s “martyrdom,” commissioning a fine art engraving of the man, one that “sold, sold, sold.” Such refinement amidst chaos defines the first half of the book. Everything about Muybridge’s life seems totally out of place and time, except for a moment in

1874, when he took his six-shooter and coolly dispatched the man who cuckolded him, prompting a sensational trial that became a nationwide obsession.

Did Muybridge’s 1860 accident aboard the Butterfield stage lead to the invention of stop-action photography, and from there to motion pictures? Ball doesn’t exactly say so, but psychologist Arthur Shimamura has suggested as much—a case of frontal lobe damage “freeing his creativity from conventional social inhibitions.” The runaway stage, drawn by “six wild mustangs,” wrecked in the Cross Timbers of Texas. Thrown from the stage, Muybridge suffered a head injury so bad he was unconscious nine days, awakening to temporary deafness and to double vision that lasted a year. He was never the same—strangeness befell him—but his life’s accomplishments all lay ahead.

It’s a story that has it all: adultery, murder, betrayal, drama, chicanery, tragedy, high achievement and prurience (Muybridge scandalously and titillatingly filmed nude adults in motion—more nudes, in fact, than any other subject).

Stanford comes in for treatment as both benefactor and robber baron. As a racehorse owner, his driving passion was equine in nature. He wanted to know “whether all four hooves of a running horse ever leave the ground all at once.” He enlisted Muybridge’s help, and the chase was on.

This is a book about time, speed and motion. To the people of Muybridge’s day, the man created an “apparatus that captures time, and plays it back.” What we take for granted, they didn’t. As Ball writes, “Movies hold the world in a perpetual present, bringing dead time (and the dead themselves) back to life.”

San Francisco is where a new kind of world began, a world that will never be the same.

—Jesse Mullins