For nearly 120 years, filmmakers from around the world have adapted the American adventurer’s novels into captivating films and television.

Read chapter one of any Jack London novel and you’ll understand why, over a century after his death at age 40, he’s still one of the world’s most beloved, and read, authors. London’s ability to plunge the reader into the mind of fascinating, completely believable people—and dogs—in life-and-death situations has rarely been equaled. Little wonder that over 170 films have been made from his writings, from as long ago as a 1907 version of The Sea Wolf, to the 2020 Disney version of The Call of the Wild. Those two novels and White Fang have each been filmed more than a dozen times.

A socialist whose writing celebrated the individual—drawing and repelling the left and the right—London loved to own things, like his ever-expanding ranch in Glen Ellen, California, and worked like the devil, writing a thousand words a day to finance it. Royalties for his film rights gave him a much-needed financial cushion.

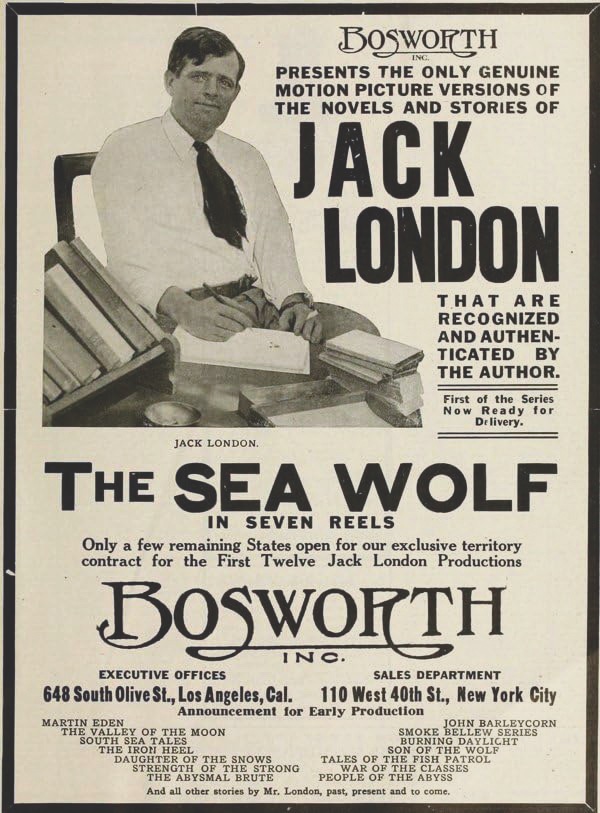

A few short films had been made, three by D. W Griffith. But London’s film career didn’t truly begin until 1913, when he met leading man/director Hobart Bosworth, who would film nine of London’s novels, beginning with The Sea-Wolf. London wrote in Motion Picture News, “It was the beginning of the picturing of my stuff, and the first time I’ve ever seen motion pictures being made, and I had one of the best times of my life.” After watching the filming of a scene in San Francisco Bay, where two ships collide in fog, sinking one, and observing the 60 performers, “jumping into the cold water time and time again, and falling down a dozen times,” it’s no surprise he concluded, “I’d rather see a motion picture actor than be one.” Still, he ended up playing a sailor in the film.

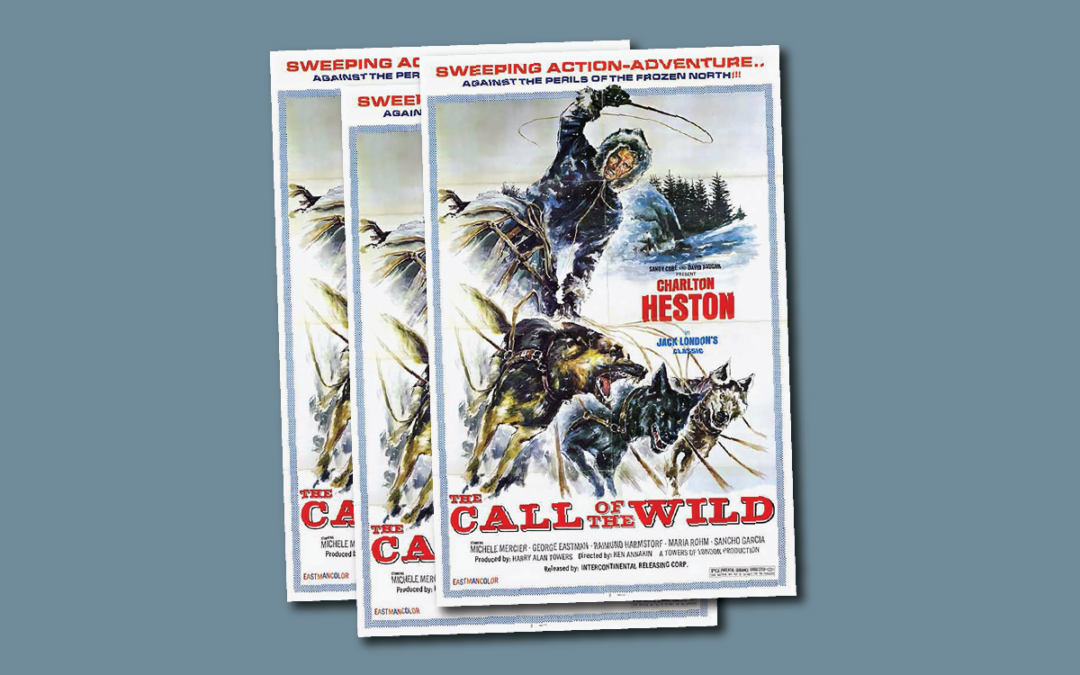

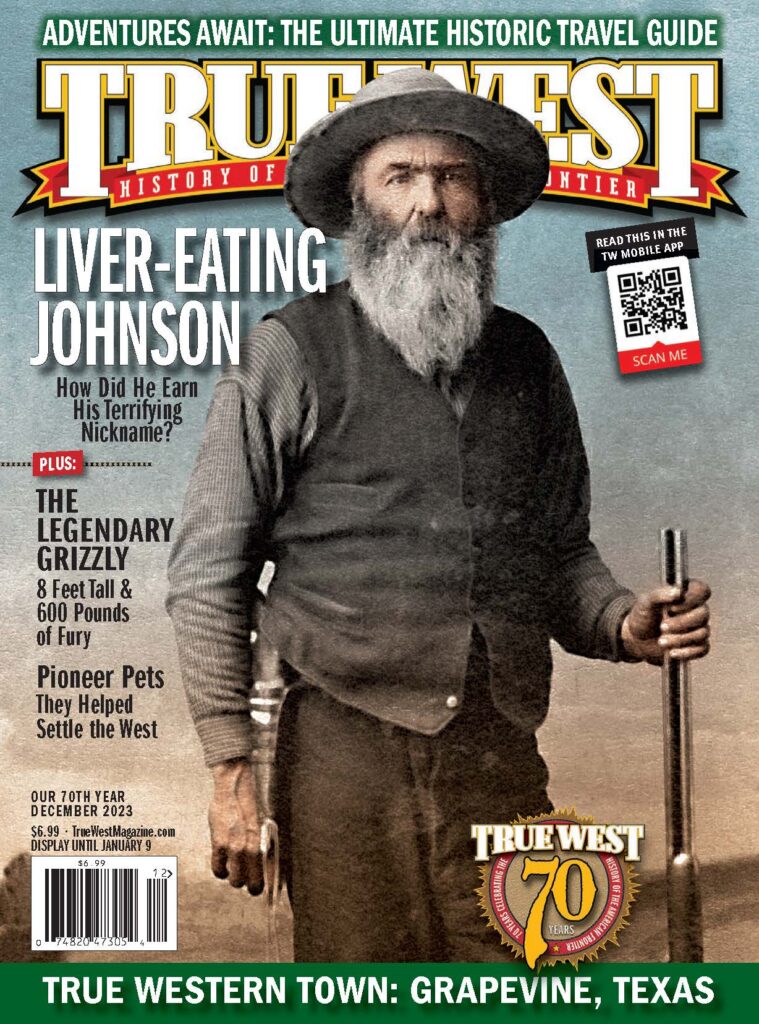

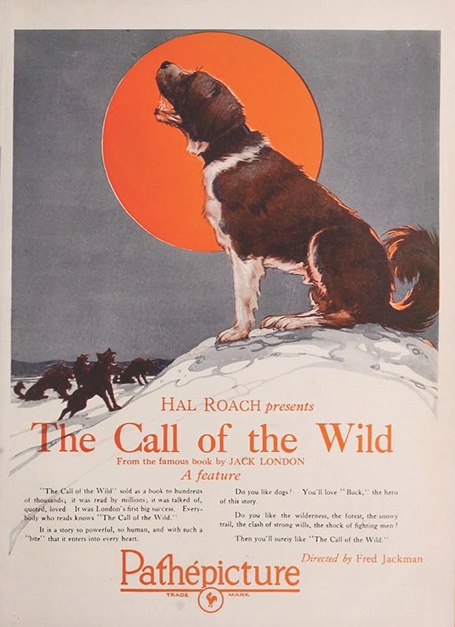

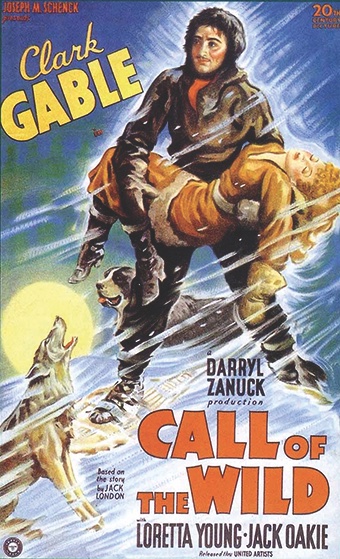

Since 1923, The Call of the Wild, one of the most beloved of Jack London’s novels, has been adapted for film and television more than 12 times.

Courtesy Hal Roach Studios (1923) United Artists (1935), Int. Releasing Corps (1972)

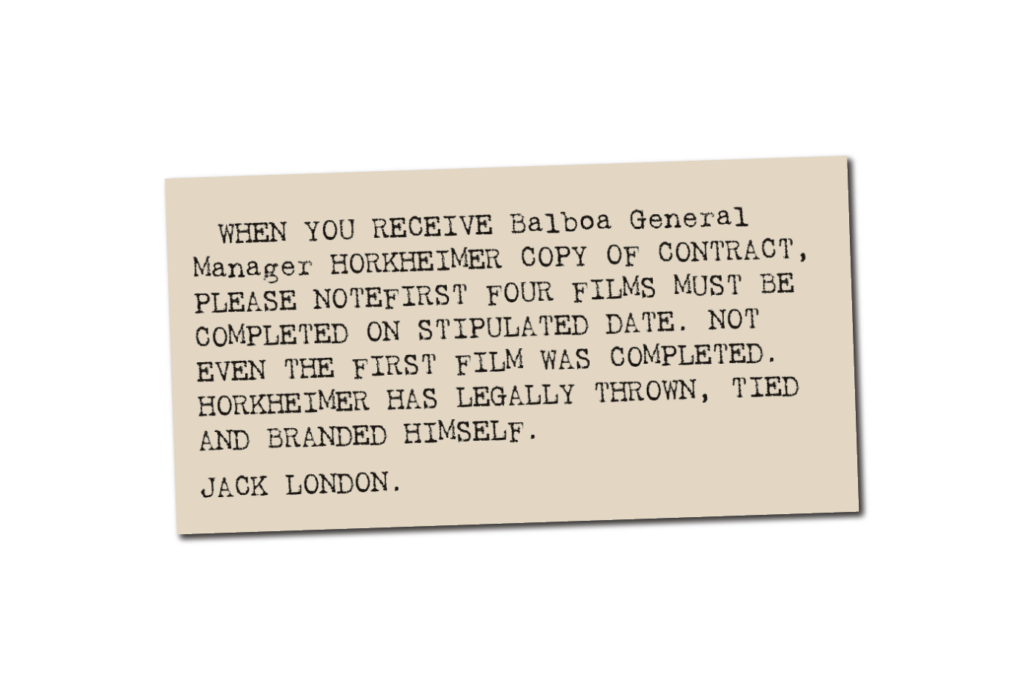

Imagine London’s and Bosworth’s fury when, a few weeks before the premiere, they learned that a competing version of The Sea Wolf was coming out! The Balboa Amusement Company had a 30-minute film competing directly with London’s feature. Balboa briefly had control of several London properties, but lost it when they breeched their contract, as London explained in a telegram printed in the trades:

The Authors League successfully lobbied Congress to change copy-right laws in favor of authors, protecting London and many others. Bosworth’s The Sea Wolf, and all of his films based on London novels each began with London’s signature on-screen and footage of him writing at his desk to prove that they were genuine. In a twist much more like an O. Henry story than a London, Bosworth’s, Horkheimer’s, the 1920 version and 1926 version of The Sea Wolf are all lost films.

London told Motion Picture World, “I did not believe at first that such power resided in the screen… Of its real might I had no idea. When I wrote The Sea-Wolf, the conception of Larson dwelt in my mind in more or less a vague outline… After I saw Mr. Bosworth’s representation of the part, my own vision disappeared and was merged in the personification of Bosworth. In the portrayal of action, which often is fight, the motion picture is supreme as a medium of expression and it carries the underlying motive, perhaps, better than the alphabet could.”

Beyond serving as his own photographer while working as an international journalist, London’s interests grew to include cinematography. Noted Motion Picture World, “Jack London has just sent…from the Pacific, 10,000 feet of undeveloped film illustrating savage life in the Islands.”

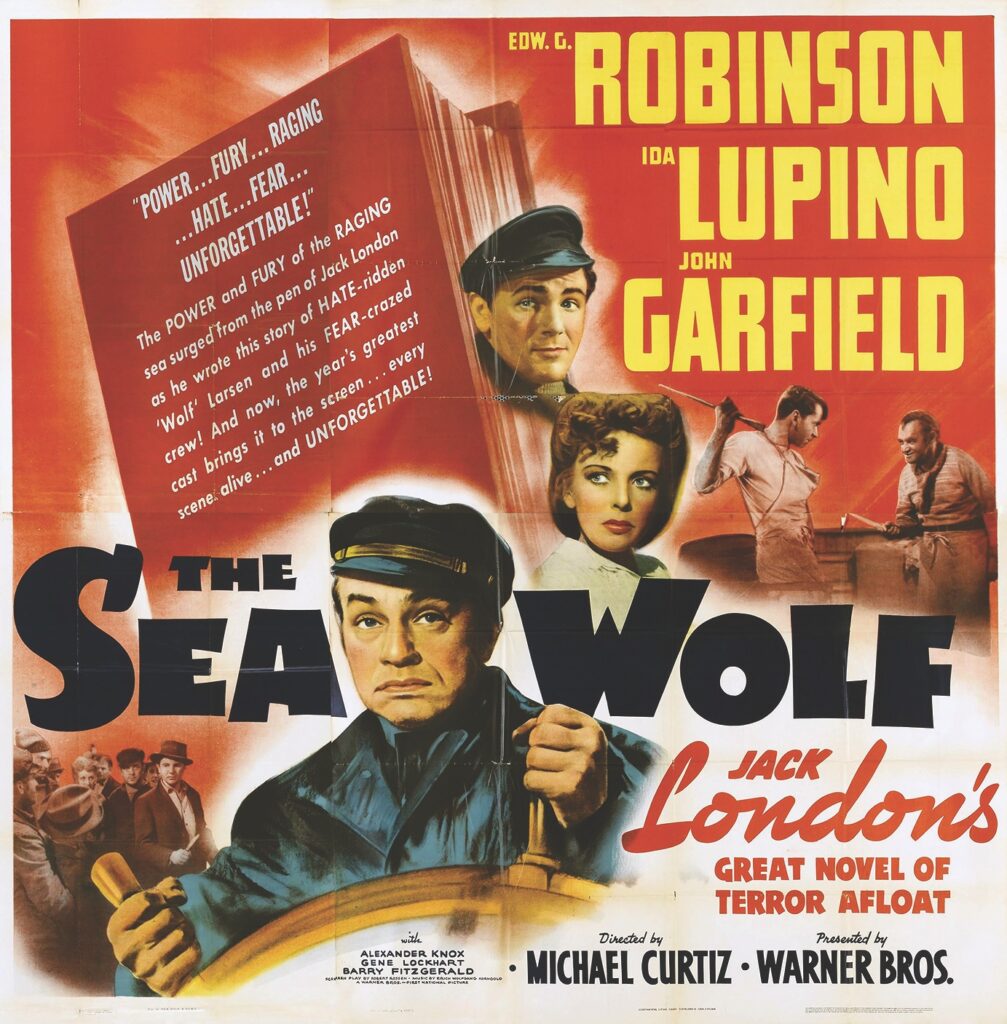

While the London silents are difficult to obtain, most of the talkies are available on streaming services. The 1941 Sea Wolf, starring Edward G. Robinson, John Garfield and Ida Lupino, an ocean-going claustrophobic masterpiece from director Michael Curtiz, is the one by which all other versions are judged. Other fine actors who have played Wolf Larsen include Barry Sullivan, Charles Bronson, Stacy Keach, and Chuck Connors in a spaghetti Western-ish version.

There is no classic version of White Fang, but the 1991 Disney film directed by Randal Kleiser, starring 19-year-old Ethan Hawke, is quite good, with the 2018, remarkably beautiful animated French version a close second. The 1973 Franco Nero version is a distant but watchable third place.

Of all the Call of the Wilds, William Wellman’s 1935 take is undoubtedly the best film, although not the truest to the source. Mostly shot around freezing Mt. Baker, Washington, the must include sequence of Buck, the Saint Bernard, pulling a 1,000-pound sled to win a bet for his owner, this time Clark Gable, was shot at the height of summer at RKO’s Western Ranch in the San Fernando Valley. Buck, hot and miserable, refused to pull the sled. In desperation, Wellman sent for a dog in heat, for motivation. A Pekinese and a French poodle were located. Wellman wrote, “Buck saw the girls, forgot about the hot summer’s day; the real heat began to boil in him, and he hurried after them. The property men had to hold back on the sled to keep Buck from breaking into a gallop.”

There were high hopes for the 2020 Disney version, because CGI was expected to make dogs do exactly what was in the script. Unfortunately, the fake dogs often have cartoonish expressions, and are unconvincing. Despite its limitations, the Ken Annakin-directed, Norway-shot 1972 film is closest to the spirit of the book, although star Charlton Heston later wrote, “For the record, it’s probably the worst film I ever made. I’m embarrassed to have screwed up Jack London.”

Among the less-known but highly entertaining London films are 1969’s The Assassination Bureau, starring Diana Rigg and Oliver Reed; Robert Aldrich’s 1973 film Emperor of the North, starring Ernest Borgnine and Lee Marvin; and 2018’s Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

Courtesy United Artists

Blu-Ray REVIEW

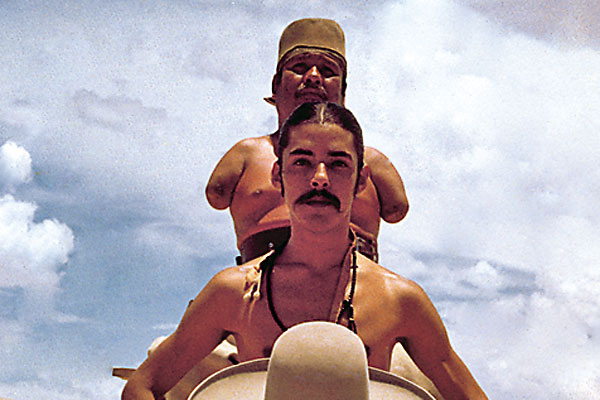

NEVADA SMITH

(Blu-ray, Kino Lorber; $24.95, Audio Commentary by Henry Parke, Courtney Joyner and Mark Jordan Legan) Largely forgotten today, best-selling 1960s potboiler author Harold Robbins was so hot that The Carpetbaggers movie producer Joseph E. Levine commissioned Hitchcock screenwriter John Michael Hayes to create a prequel around Alan Ladd’s supporting character, Nevada Smith. The result is the story of a teenage half-Kiowa, who doesn’t drink or gamble or read, tracking down the men who murdered his parents; it’s intensely believable and full of surprises. Though too old and too white, Steve McQueen gives one of his best performances, with powerful direction of both emotion and action by Henry Hathaway, and glorious photography by Lucien Ballard. As hateful villains, Martin Landau, Karl Malden and Arthur Kennedy are revelations. And Suzanne Pleshette, Janet Margolin, Josephine Hutchinson and Johanna Moore play fresh, original female characters.