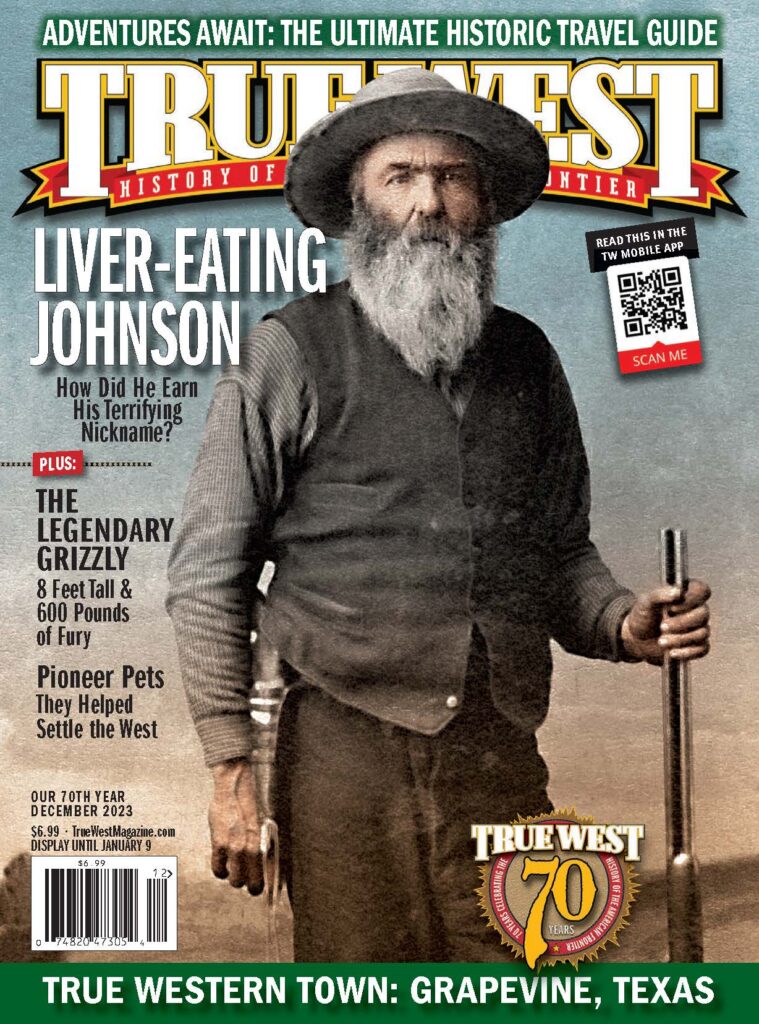

How did he earn his terrifying nickname?

The sun lay low on the horizon over Battle Mountain in northwestern Colorado. The big man on the imposing black stallion veered off the trail and onto the shale and gravel scattered along the hillside and dismounted.

He stood for a moment, sniffing the air. Satisfied that there were no enemies nearby, he unfastened his pack, lifted the load from his horse and threw it like a pillow full of feathers off to one side. It was no problem for the most powerful man who ever strode the Rocky Mountains. Or, at least, so legend said.

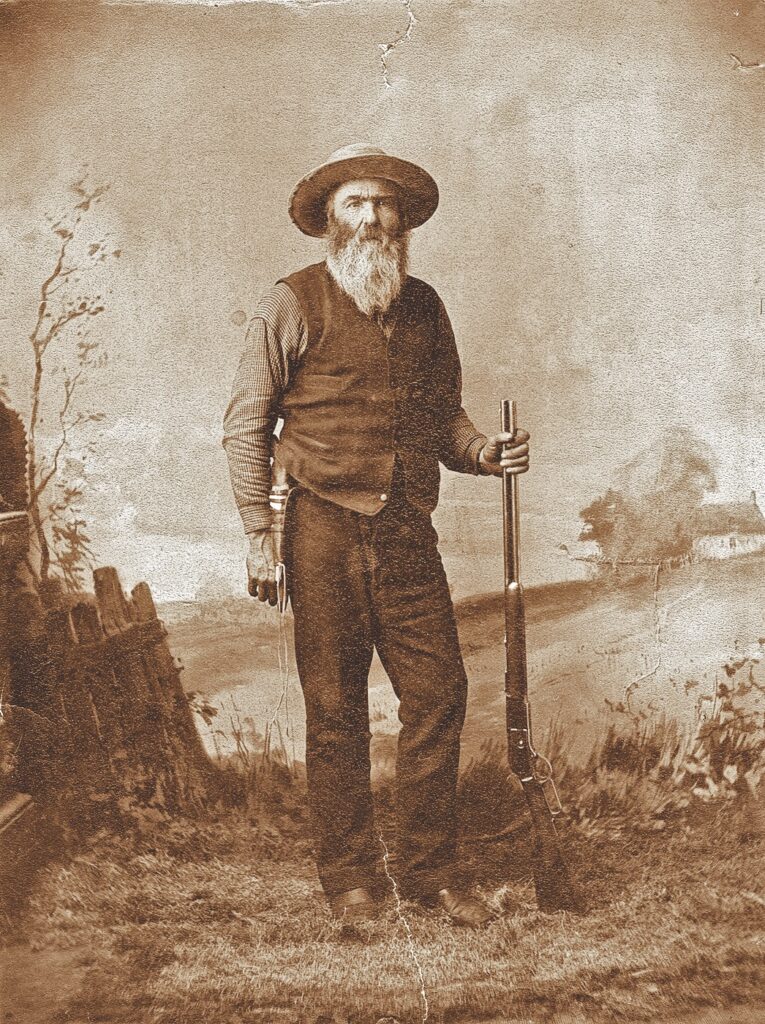

The man who had come to be called Liver-Eating Johnson, or Dapiek Absaroka by the Indians and “Crow Killer” by the whites, uncinched and removed the saddle from his horse. The setting sun silhouetted his six-foot-three-inch frame and 240 pounds of muscle below the thick red beard that had become his calling card.

Staking his pack animals in a small patch of greenery among the stones, he whispered to them that all was well and they’d be safe that night. Mountain men often talked to their animals when no one else was around. Johnson hadn’t seen another soul for weeks.

Near the belongings he had thrown to the ground lay an oblong pile of stones in the shape of a grave. He removed the two top layers, reached down into a hole, and removed a hinged copper kettle. He loosened its latch and opened it up. Reaching in, he lifted out the skull of a woman followed by a second, smaller one. After that, he removed an eagle’s feather and several mementos, including a necklace and armbands. He checked the items carefully before putting them back in the kettle and returning it to its hiding place. He mortised in the stones and, as darkness settled over the mountainside, he sat back against a boulder and pulled on his pipe while he watched Battle Mountain shimmer against the twilight.

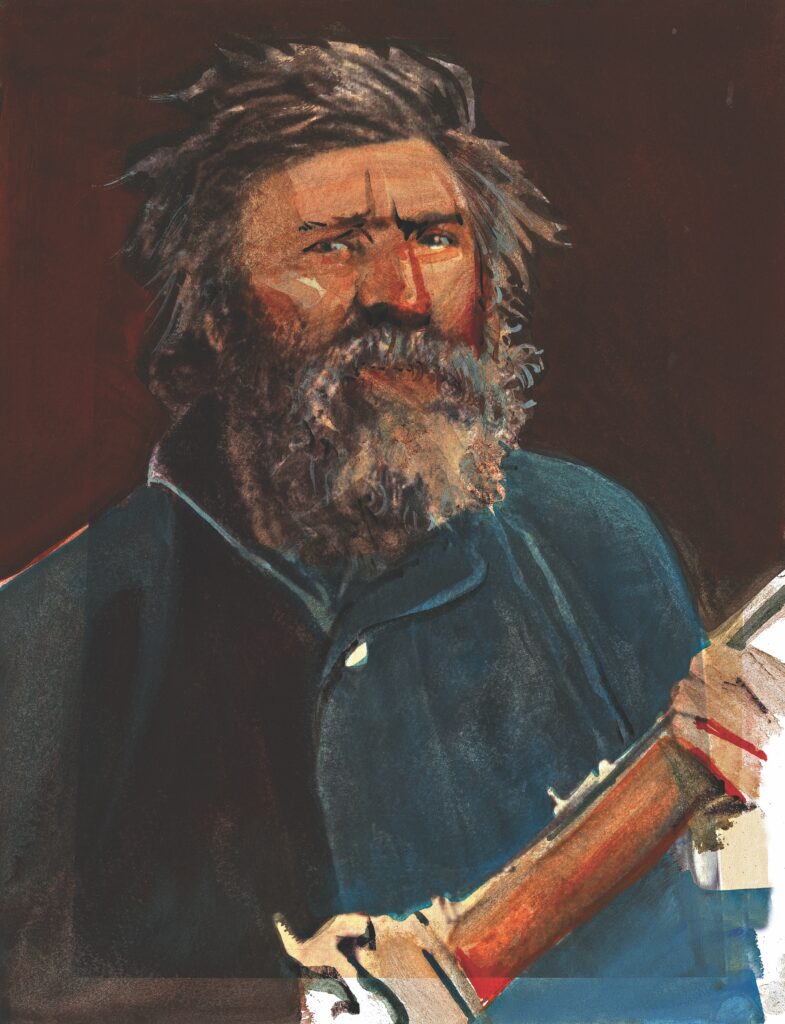

Illustration of Liver-Eating Johnson by Bob Boze Bell based on a Photo Courtesy Montana Historical Society

He thought back four years to the day he had made that monument of rocks. He had returned from a winter’s trapping in the Uintah Range to find his world uprooted. When he neared his cabin on the banks of the Little Snake, he noticed no one there to welcome him home. The previous fall, when he had bid his Flathead wife goodbye, they had exchanged tender words to one another. Now, only stillness greeted his return. The greatest tracker in the mountains knew the danger of silence in the wilderness, so he tethered his animals and sneaked up toward the cabin on foot. Peering from a hiding place, he felt a dead emptiness until, suddenly, the fluttering wings of a huge vulture lifting off startled him. The emptiness turned in an instant into anger.

Cursing, he stepped forward with his Hawken fully cocked and hoping to find an enemy to send to the happy hunting ground. But when he barged through the door, only emptiness greeted him. Emptiness except for two skulls and other bones near the doorway. He shouted as two more vultures lit out. He picked up the small skull and shook his head. He’d had no idea his wife had been carrying his child when he’d last said goodbye. He knew instinctively what had happened. And if the killers could have seen his eyes at that moment, they would have shuddered in fear.

Stepping back outside, he discovered the spot in the shrubs where the braves had hidden. When he picked up the eagle’s feather, he knew the killers were Crow.

Returning to the cabin, he located a heavy wooden box that the Indians hadn’t taken, although they had spirited off most everything else of value, including two packhorses from the corral near the house. The red-bearded giant removed from the box a hinged copper kettle, gathered together what remained of his family, and placed their bones in the vessel along with the feather.

A Man Unmatched in the Mountains

It was 1851 when Johnson found himself again on a layover along the trail to Fort Laramie. His pipe glowed in the darkness as he pondered a plan for revenge. He knocked out the last remaining ashes, climbed to his feet and sniffed the clean, pungent air. Reassured that he was alone (he could smell an Indian a mile away, he insisted), he finally rolled up in his blanket and fell off to sleep face-up on his back.

The wives and daughters of soldiers stationed at the old fort had heard of his coming. So, when he rode in, they closed their shutters and peeked through the cracks at the mighty man of the mountains as he dismounted and strode by, bloody scalps dangling from his belt. They shuddered at the sight of his red beard, thinking of the bloody vendetta and bloodier livers for which he had a reputation of devouring raw, and they pushed their children back behind their skirts. Some of them—the bravest boys of the bunch—wanted to get a closer look at the Crow Killer, but their mothers had caught the cold gray glint in the killer’s eyes. One later recounted that she felt the chill of Death in his passing.

Men who had met him before spoke to him in the byways but were repelled by his eyes, which seemed fixed on something afar. He said nothing to anyone—not even to “Bear Claw” Chris Lapp and Del Gue, his staunchest allies. According to Raymond Thorp, writing of the incident in The West in September 1964, Lapp raised his hand and began to speak when Gue suddenly quieted him. “Leave the Liver-Eater alone, he’s on a trail.”

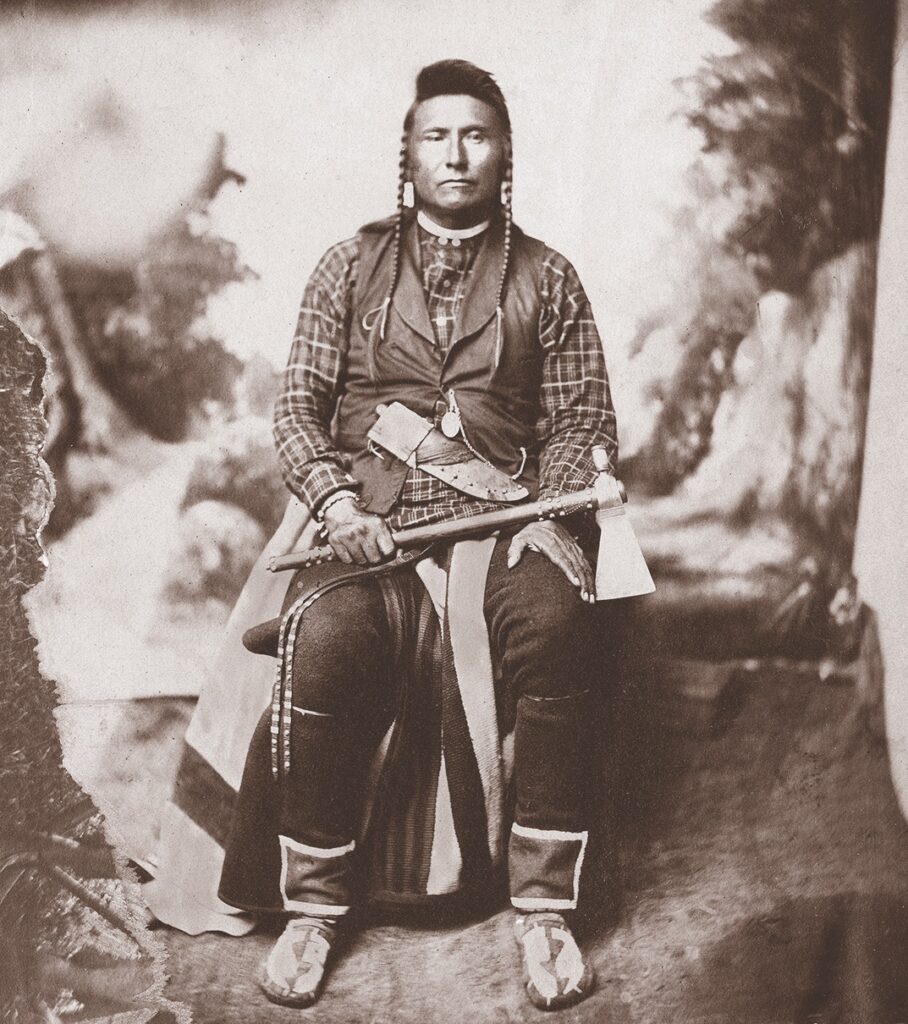

Alfred Jacob Miller’s “Warrior and His Squaw” Courtesy The Walters Art Museum Online Collection

The mountain man turned into a store, where he bought some salt, sugar and flour, trading several scalps he had taken. Some of the gawkers wondered if he had eaten the livers of those braves, but no one dared to ask. From the man’s belt dangled a bowie knife with a twelve-inch blade sheathed beside a Colt Walker revolver, each with rosewood handles.

The man went about his business as silently as the wind as he made up his pack and strode off toward the corral where his horse was quartered. Several men had gathered there and watched him saddle the powerful black before tying on his supplies. The owner had talked about how the animal stood watch over Liver-Eater while he slept, neighing a warning whenever an Indian got within earshot.

Liver-Eater heard the crowd mumbling as he prepared to mount but thought nothing of it, for it was nothing unusual. Finally, he climbed aboard the saddle, placed his Hawken behind the horn, and pointed the beast’s flaring nostrils west.

“Wonder whar he goes?” someone asked.

“Wharever ther’s Crow Injuns,” another answered. “Thet ol’ coon is on a death trail.”

The stallion threw back, whinnied and broke into a trot.

A Heart Full of Pain

Once safely back home, he went to his sepulcher. The Swan and her baby would sleep better, he knew. With the kettle before him, he took out the skulls and the lone eagle feather which had first told him the identity of his enemies. Now, from the doeskin bag he had brought from his spoils in the Bitterroots, he pulled the scalps, twined together, along with the killer’s eagle feather and the body ornaments of the brave.

While he sat there fingering his keepsakes, his nose began to quiver, and he knew live Indians were present. Black eyes glistened from behind the rocks somewhere, but a mountain man was a fatalist with no fear of sudden death. Very slowly and carefully he returned his property to the kettle, closed the lid, and placed it in his family tomb. He took the time to mortise it in, knowing that his observer would have killed him from ambush long ago, had he so chosen. Then, still as carefree as a bird, he got to his feet and ambled back down to the cabin.The word would go forth from Johnson’s Indian stalker that the Crow Killer had a reason for his madness. He had seen Liver-Eater’s two skulls—one tiny and one from a grown woman—two feathers, two scalps, and several ornaments from a successful skirmish. What Indian wouldn’t make the connection? As for the watcher, was he Arapaho, Sioux, Gros Ventre, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Piegan? It was impossible to know. Regardless, news traveled ahead to the forts and settlements, the trading posts and encampments—wherever men gathered throughout the wilderness. Why had a man with no sentiment started such a bloody vendetta? He was incapable of love, according to those who knew him, and most certainly he was incapable of loving a Native woman.

But those who knew him had forgotten that the Crow had destroyed not only his wife and his young child but also his property. The woman and baby had belonged to him.

Suddenly, as news of the reason behind the vendetta spread, the lonely white women of the frontier found themselves empathizing with him instead of standing against him. Practically overnight Liver-Eating Johnson had become their knight in shining armor, their patron saint of retribution.

He had proven his single-handed, single-minded determination to right the wrongs done to him and his family. It was more than a personal vendetta; it was the Code of the West. Little could anyone have known, but Johnson was far from finished. In fact, he was determined to carry on the feud with his archenemies for the rest of his life—or until every last one of them had paid the price. Which meant he would continue waging war against the mighty Crow Nation for close to a quarter century. By then, his victims would total more Crow warriors than there are days in the year.

Facts about John “Liver-Eating” Johnson

• He was born either John or William Garrison in 1824 near Hickory Tavern in Hunterdon, New Jersey.

• He was most likely one of seven children, the son of impoverished Scot-Irish or Scot-German parents, Isaac and Eliza-Metlar Garrison.

• In 1838, at age 14, Garrison ran away from his abusive home life and joined a whaling schooner crew.

• He joined the U.S. Navy in about 1843 and served aboard naval and merchant marine ships for maybe a year until he went AWOL in San Francisco.

• He changed his name to John Johnston after deserting the Navy and worked his way east to St. Joseph, Missouri. There is no evidence he fought in the Mexican-American War. He would later drop the t in his name.

• Johnson went west to Wyoming’s Yellowstone Country in 1844. Within a year, he set out to be a trapper.

• In addition to “Liver-Eating” or “Liver-Eater,” Johnson was also known as “Crow Killer.”

• He served in the Union Army for two years during the Civil War.

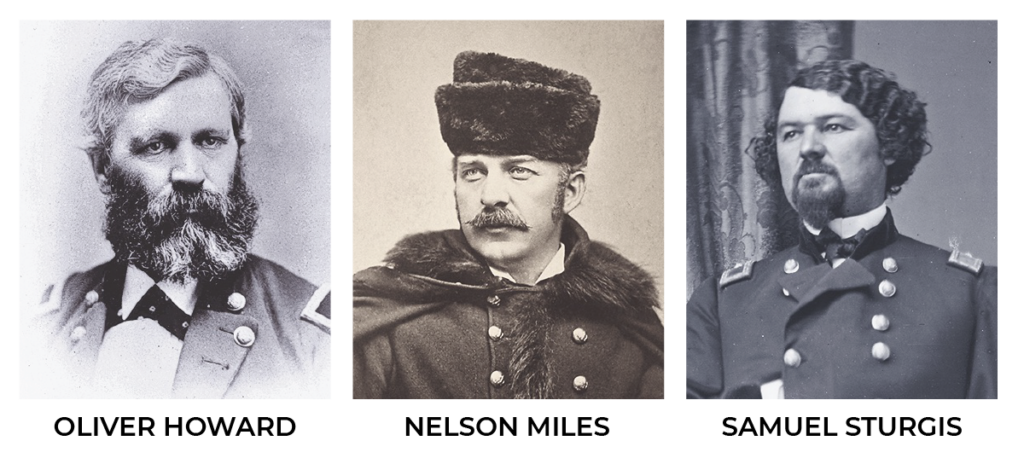

• In the Indian Wars of 1876-77, he served as an Army scout.

• In 1881-82, he lived in Miles City, Montana Territory, and for a short while served as Custer County’s justice of the peace.

• In 1884, Johnson was a member of Thomas Hardwick’s short-lived Great Rocky Mountain Wild West Show.

• He served as the constable of Red Lodge, Montana, for seven years, from 1888 to 1895, until the ailments of old-age prevented him from serving any longer.

• Unable to take care of himself, he moved to the National Soldiers Home in Los Angeles in December 1899 and died on January 21, 1900. He was interred in the Los Angeles National Cemetery.

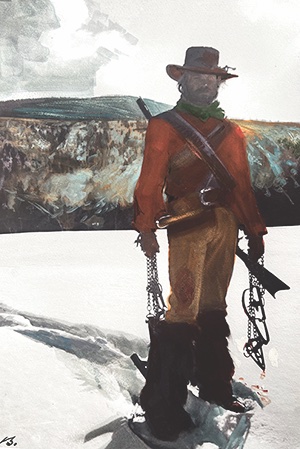

• Johnson became internationally famous when Robert Redford portrayed him in Warner Bros.’ 1972 film Jeremiah Johnson.

• In 1973, Lancaster, California, middle-school students, inspired by their teacher, helped lead an effort to have Johnson moved from his final resting spot near the 405 freeway in Westwood to Red Lodge, Montana. When Red Lodge citizens balked, the students’ teacher Tri Robinson contacted a friend in Cody, Wyoming, who was more than willing to have the fabled fur trapper reburied at Bob Edgar’s tourist attraction, Old Trail Town. With approval from Congress, Johnson’s remains were moved to Wyoming and reburied. Robert Redford even acted as a pallbearer.

All information on Johnson’s life is from D.J. Herda’s The Never-ending Lives of Liver-Eating Johnson (TwoDot).

How Johnson Earned His Nickname

Colorization by Bob Boze Bell/

”Jeremiah Johnson” Still Courtesy Warner Bros.

Johnson earned his terrifying moniker during an Indian fight on the Musselshell River in 1868.

A fellow frontiersman named Ross, who Johnson described as “as a squeamish old fellow” saw him stab an Indian to death and part of the warrior’s liver came out.

Johnson teased Ross and dared him to eat some and said “it’s just as good as antelope’s liver. Have a bite! and I kind of made believe to take a bite.” Then Ross he threw up his guts.

“And he always swore after that he seen me tear a liver out of a dying Injun and eat it. But that ain’t so. I was all over blood and I had the liver on my knife, but I didn’t eat none of it. The liver coming out was unintentional on my part. But Ross he vowed ’twas so and I never got rid of the name.”