It was a hot August night back in 1900 when 600 Phoenix residents—one of every five citizens in this dusty spot in the Arizona Territory—gathered in the Dorris Opera House in downtown.

It was a hot August night back in 1900 when 600 Phoenix residents—one of every five citizens in this dusty spot in the Arizona Territory—gathered in the Dorris Opera House in downtown.

They had come not to talk about lawless renegades or quick-triggered gunmen, as you’d expect from Arizonans in those days, but to talk about water. Specifically, about storing water. But most importantly, about their very survival.

Meetings like this were held throughout the West, as a growing population quickly realized the importance of water, immediately seeing it as a major reason to battle over who had it, where it came from, how much there was and who got a share.

In Phoenix, there was no factor more obvious than the need for a plentiful and steady supply of water. The people gathered in the ornate opera house knew to their bones that they were doomed if things didn’t change.

Phoenix and the vast valley around it depended on the Salt River for agricultural water. Unfortunately, the Salt was one of the most erratic rivers in the nation. One year it would flood the town and its fields, the next it would disappear and be nothing but a dry bed. Phoenix had already learned its water supply was too undependable. Stability was shaky; growth was impossible.

So they investigated the idea of a dam where they could store water in wet years for the dry years. That August meeting at the opera house had been called to hear from the committee that went searching for the right spot.

They’d found it, they reported, 80 miles east of Phoenix, where Tonto Creek joined the Salt River. On the face of it, the site was so absurd, it could have been on the moon. “You’re building a what, where?” someone must have asked, because there was no train from here to there; not even a road. There was nothing there except a gap between the mountains and the dreams of a thirsty valley.

Of course, nobody in that room had any idea where to get the millions it would take to build a dam. As a territory, Arizona wasn’t allowed to assume such public debt and besides, there was nobody to lend Arizona that kind of money.

But what happened that night was the first awakening of what would become the Salt River Project (SRP), now the nation’s third largest utility company. But then, it was the lifesaver of a wide spot, along a bad road, known as Phoenix.

Arizona’s ace in the hole

The West will forever be in the debt of former President Teddy Roosevelt. He was responsible for the single most important thing the federal government has ever done for the region: He’d been in office only eight months in 1902 when he signed the now historic National Reclamation Act that provided federal loans for water projects in the vast, undeveloped West.

Arizona leaders had been instrumental in lobbying for the act—a controversial measure that some Eastern congressmen saw as folly—and they were first in line. But Arizona was still just a territory, and also lined up were the states of Nevada, Wyoming, Colorado and Montana.

But Arizona had an ace in the hole: It had a whole valley of landowners willing to bet the farm that the dam would bring them prosperity. In an incredible act of economic courage, all the farmers in the Salt River Valley used their acreage as collateral for the loan. Some 240,000 acres were pledged (with the prospect of each farmer owing an astronomical $60 per acre if water sales didn’t cover the repayment). That commitment so impressed Washington that the Arizona Territory got the biggest of the first five reclamation projects.

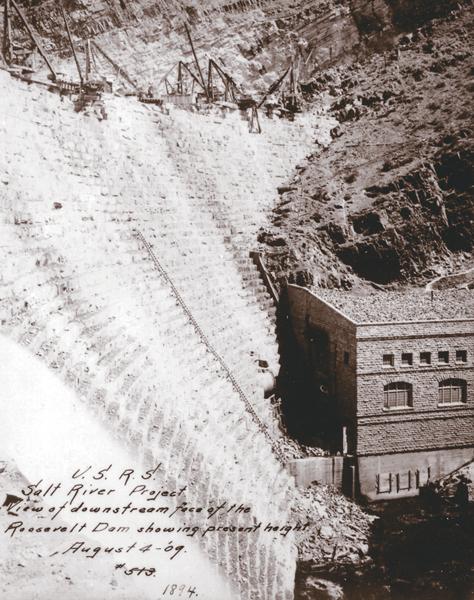

In honor of the president who’d go on to be the nation’s conservation warrior, Arizona named its project Roosevelt Dam. It would be the world’s highest masonry dam: 184 feet thick at the base, 16 feet wide at the crest and 280 feet high. It was supposed to take four years to build, but the dam ended up taking six years because it had to be started three times—twice, its foundation was flooded out by that erratic Salt River.

But even before the crews could construct the dam, they had to build a road to get people and supplies up to this remote area. And, of course, they had to build a town.

A dry town

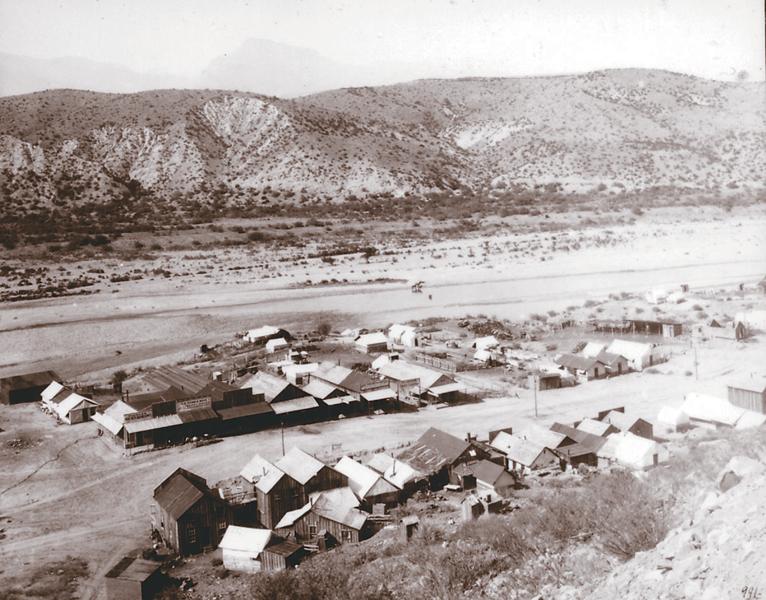

Roosevelt, Arizona, held a lot of distinctions: from being built almost overnight for a specific purpose, to having various ethnic “neighborhoods.” But nothing so set it apart from every other town in Arizona Territory—and from most other towns in every Western state—than that it was dry. While most towns started with a saloon and worked onward, Roosevelt never had a saloon at all, per instructions from the Reclamation Service.

But SRP historians say Roosevelt did have a Mexican restaurant, a French restaurant, a theatre group, schools, churches and electricity. With a population over 2,000, it was one of the largest communities in the territory.

The workforce was as varied as the new nation: Apache Indians worked beside Mexican laborers, who learned with Italian stonemasons, who joined Anglo bricklayers. While they lived in separate neighborhoods or areas (the Indians lived in wickiups outside of town, using empty cement sacks as covering over the cactus frames), everyone was integrated in the sports teams that formed the major recreation: bowling and baseball.

The road built to the dam site was called the Apache Trail—some say because Anglos thought the name would bring tourists; others say to honor the Apaches who were the primary road builders. But whatever the true story, the road did become one of Arizona’s first tourist routes, and to this day, it is still used to go to the dam for picnics.

President Teddy Roosevelt came to dedicate the dam on March 18, 1911, pressing the button that released the first water flow at 5:48 p.m.

Roosevelt Dam became the cornerstone of SRP’s water storage and delivery system. Today, it is one of six major dams owned by the utility company.

And Phoenix, just a little town when folks met in the opera house to dream of a rosy future, is now the nation’s sixth largest city with over a million people.

But it would still be just a dusty nothing, if not for the water.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy SRP Research Archives unless otherwise noted –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Orme Lewis Collection, SRP Research Archives –