June 25, 1876

George Armstrong Custer’s mind is racing with military strategies and tactics. As usual, he is reacting to a fluid battle situation (something at which he’s a genius).

After ordering Maj. Marcus Reno to attack a large Indian village nestled in the Little Bighorn Valley, Custer notices 50 “hostiles” on his right flank and gives chase. When they scatter, Custer keeps going, leading his command north. As he rides, he formulates a new battle plan without telling his other commanders (this is one of Custer’s biggest faults as a leader).

Now he’s looking for a river crossing as his battalion continues north at a gallop along the barren shoulders of the Little Bighorn River (see map, opposite page).

The regiment turns into a broad, fantail ravine and follows it down. As they traverse the gully, Custer’s command starts taking fire from the rear. Wolf Tooth, a Cheyenne who had been scouting with 40 to 50 warriors, sees the soldiers heading for the village and opens fire.

With Indians behind him, Custer cannot commit his entire command, so he sends Algernon Smith and E Troop to test the crossing. Meanwhile, Custer and four companies hang back, riding the ridgeline above the river as a rear guard.

On Smith’s return, Custer learns that the ford at Dry Creek (a.k.a. Muskrat Creek) is “too miry” and full of bogs.

A small number of warriors (believed to be four) are defending this crossing from the village side, but more important, Smith notes that the Indians, mostly noncombatants, are fleeing to the west and northwest.

This is Custer’s worse fear: that the inhabitants of the camp will escape.

Now Custer is even more determined to find a crossing that will head off the fleeing Indians.

Wolf Tooth and his warriors continue harassing and sniping at the troops from long range, but Custer is not yet worried. He has been in hundreds of fights during his storied Civil War career and is considered by some to be the top Indian fighter in the U.S. Army.

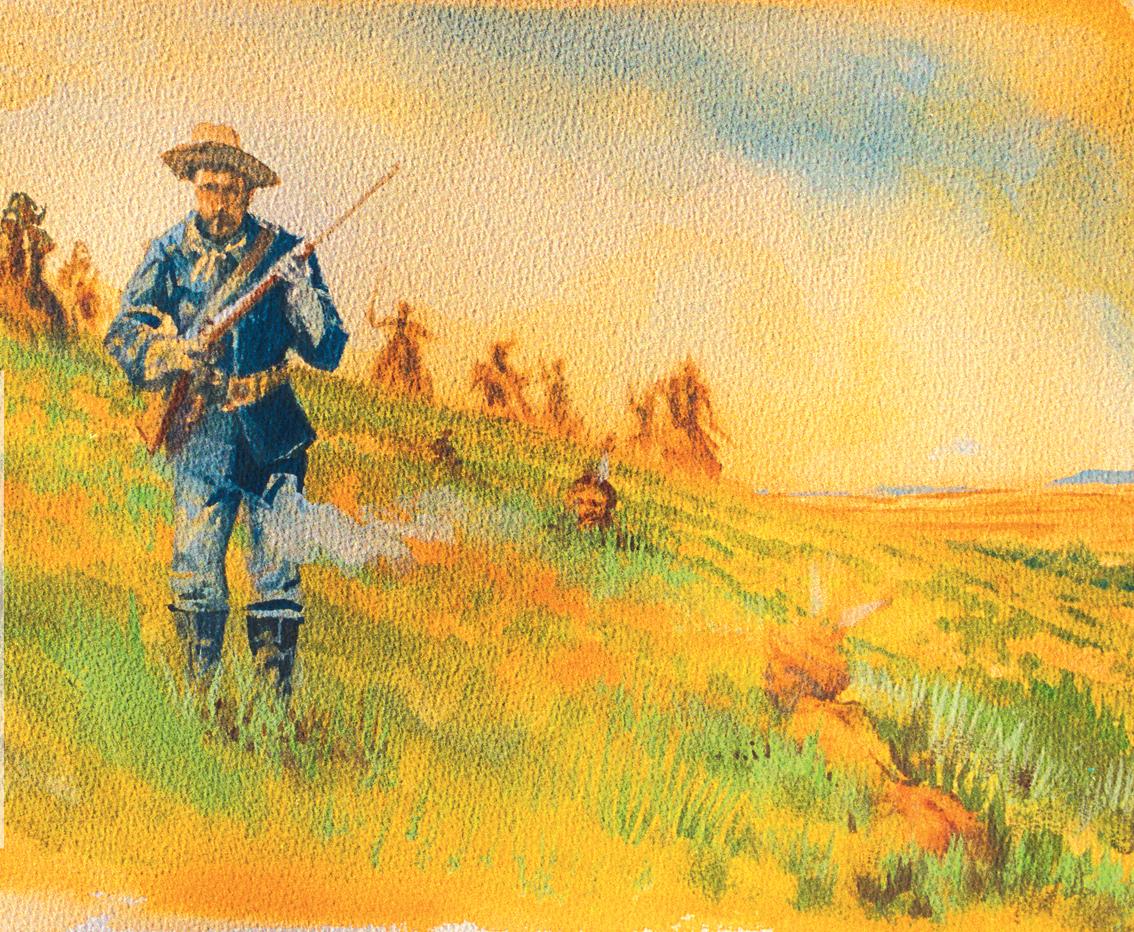

Custer leaves three of his five companies—I, C and L—fighting Wolf Tooth’s men (and to act as a connection when Capt. Frederick Benteen and the pack train come up). With Companies E and F, Custer rides northwest off the ridgeline and into a broad plain that empties toward the river. As Custer and his troops approach the river bank, they are fired on by a group of warriors who are guarding the women and children.

Members of F Company dismount and form a skirmish line. Instead of having his troopers each hold three horses (see 1876 cavalry tactics, p.45), Custer orders more firepower on the ground and has them each hold eight horses (a bold but risky technique he used on the Yellowstone three years earlier). Indians waving blankets and shooting cause the soldiers’ horses to stampede. Warriors quickly capture them. With most of F Troop on foot, Custer knows the entire operation and his command are in grave peril.

While Custer is attempting this second crossing, word is sent to the warriors fighting Reno that soldiers are trying to capture the women and children. Virtually all the Indian combatants in the Reno sector disengage and race pell-mell toward the slopes above the north end of the village.

Meanwhile, F Company is retreating back toward the ridgeline, where the rest of the command has gathered, as Company E (which still has its horses) lays down covering fire. After a one-mile run, F Company finally gains the top of a ridge. E Company dismounts and fights in a skirmish line to cover its horseless comrades. A 20-minute gunfight ensues while Custer des-perately tries to stall until the pack train and reinforcements arrive. (Custer’s brother Boston had told him both were six miles away.)

As the Indians become increasingly bolder, more and more cavalry horses are stampeded and captured. A charge by C Company to drive back some of the newly arriving Indians meets with disaster as the soldiers are cut off and surrounded. While only three die, panic sets in all along the skirmish line as troopers bunch together and begin

to run.

With over half of his command unhorsed, Custer realizes his only hope is for Capt. Benteen and Maj. Reno to save him.

Helplessly watching the collapse of his command, Custer and his headquarters staff kill horses to make breastworks on the highest point of a hillock. Panicked soldiers begin running toward the hill as Indian suicide riders step up their bold attacks.

As if things could not get any worse for Custer, most of the warriors (an estimated 1,500) who were fighting Reno now come pouring onto the battlefield from the south, across the bluffs, through the water and up all the draws and coulees.

Company E holds a position west and below Custer’s location to protect Custer’s flank from warriors who are moving in from the northwest. In spite of this, suicide warriors successfully get past Company E and stampede all of the troopers’ remaining horses.

A two-hour gun battle that started slowly now gains a frightening momentum as waves of warriors on horseback and on foot quickly overrun the few able soldiers on the hilltop with Custer and kill them all.

With some 190 dead and dying soldiers strewn for hundreds of yards, the warriors turn their attention to the 15-20 men from Company E, who are surrounded, on foot and out of ammunition. Gamely, these men make a run for it, many still carrying their empty weapons to use as clubs. They are all chased into a deep ravine and killed. The battle is over.

The controversy begins.

How Big is the Indian Village?

Custer and his officers first get a good look at the Sioux and Cheyenne’s encampment from a distant ridge (see 5 on map). The camp is big, but it is not as large as many reports will later indicate. Although Black Elk later testifies that it was the biggest Indian village he had ever seen, Benteen’s estimate of 10,000 Indians in the camp is likely a gross exaggeration. Benteen has several motives for embellishing the truth: a huge enemy encampment helps cover his lack of action, and the inflated numbers may encourage Congress to stop military cuts.

One problem in estimating the village’s size is that when the attack occurs, Indians begin fleeing with their tipis. After the battle, the warriors move their camp 1.5 miles north of the old village site. The troops who later investigate the battleground assume the village is three miles long when in reality, they are seeing two village locations.

Most historians today estimate the hostiles’ strength at 2,000 warriors, which is almost a 10-to-one ratio against Custer’s 210 soldiers.

Why Does Custer Believe the Village is Empty of Warriors?

“Then Custer halted his command on the high ridge about 10 minutes, and officers looked at the village through glasses. Saw children and dogs playing among the tepees but no warriors or horses except few ponies grazing around. There was then a discussion among the officers as to where the warriors might be and someone suggested that they might be buffalo hunting, recalling that they had seen skinned buffalo along the trail on June 24. Custer now made a speech to his men saying, ‘We will go down and make a crossing and capture [not kill] the village.’ The whole command then pulled off their hats and cheered. And the consensus of opinion seemed to be among the officers that if this could be done the Indians would have to surrender when they would return, in order not to fire upon their women and children.”

—John Martin, the last trooper to see Custer alive.

Do Eager Beaver Doom Custer?

Mary Crawler, one of the Indian participants said, “Custer’s men got to the river above the beaver dam where the water is deep.” She goes on to explain that the ford at Dry Creek was flooded out because of a beaver dam downstream, and that the Indians knew to cross below the dam.

1876 U.S. Cavalry Tactics & Strategies

In 1874, Emory Upton codified new cavalry tactics in a manual that incorporated a “set of fours” as the basic cavalry unit, or squad.

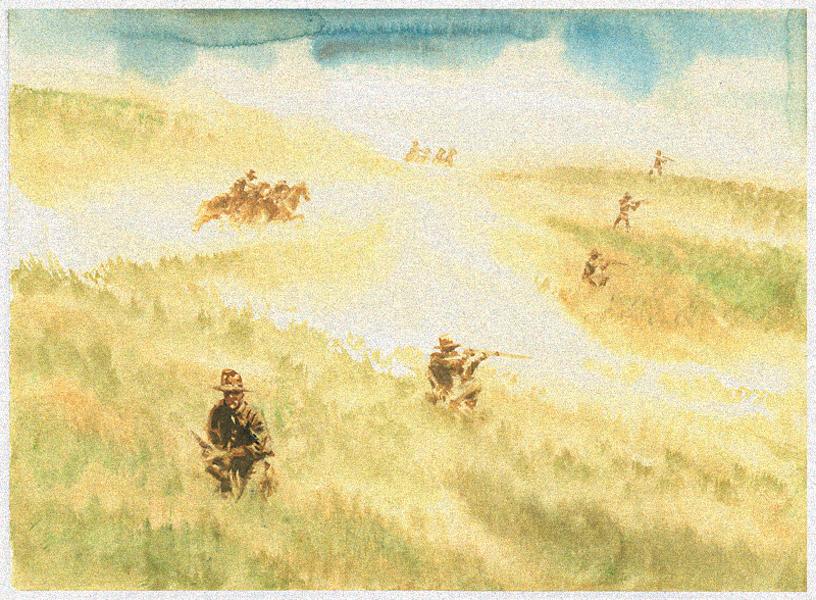

Unlike in movie portrayals, cavalrymen in the 1870s seldom fired from horseback. Instead, cavalry companies (38 to 44 men in Custer’s case) dismounted and spread out in a skirmish line. One man from each squad gathered up the dismounted troopers’ horses and held them in the rear. The dismounted skirmishers knelt for steadier aim.

In the case of the Little Bighorn battle, only one company at a time is deployed in a skirmish line, with the remainder held in reserve. For the first hour of fighting, this single dismounted company (I Company) effectively holds the Indians in check. It is only after the warriors from the Reno fight creep onto the Custer battlefield (the tall grass provided perfect cover) that the Indians are able to isolate the skirmishers and overwhelm them.

Did Custer Save the Last Bullet for Himself?

Two days after the fight, on June 27, relief troops finally took a look at the Custer battlefield. Peering through binoculars from the Little Bighorn Valley floor, Lt. James Bradley thought he saw skinned buffalo. Captain Thomas Weir later remarked, “My God, how white they look!” Of course, the white patches they all saw glittering in the distance were the stripped and mutilated bodies of George Armstrong Custer and his entire command.

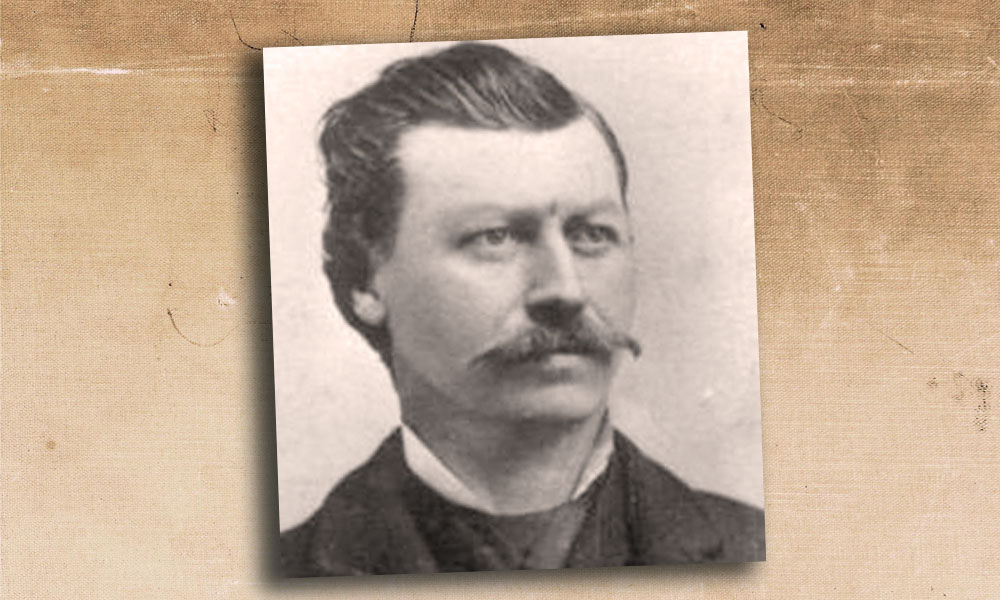

Custer’s body was found amid a knot of slain men and horses just below the western summit of a small hill. Lt. Edward Godfrey and another soldier counted 42 bodies strewn across the slope.

“We found no powder burns,” Godfrey reported about Custer’s body, implying he didn’t commit suicide. (When a gun is fired close to the body, it leaves powder burns.) Godfrey and others claimed that besides two bullet wounds, Custer “had not been touched.” This was a blatant lie, which Godfrey later admitted in a letter to a friend. His motive for lying, he said, was an attempt to spare Custer’s wife, Elizabeth.

In the letter, Godfrey confessed that Custer’s left thigh had been slashed to the bone (Indians believed that it would impede mounting a horse in the afterlife); a finger had been severed; and an arrow shaft had been shoved into Custer’s penis.

If Godfrey was lying about the mutilation of Custer, should we trust his statement about the powder burns? Or was he trying to spare Elizabeth and the nation from the trauma of knowing Custer had killed himself?

Custer had two bullet wounds, as Godfrey reported. He had been struck with a bullet near his left temple and another in his ribs, near the heart. Tellingly, the rib wound and thigh slash were bloodless, while the temple wound was bloody. The wounds indicate that the head shot happened first because Custer’s heart was still pumping blood, and that by the time someone shot him near the heart, he was already dead (so scratch all the paintings of Custer standing and holding his side).

“The odds of being shot in the temple in a battle are astronomical. It has always seemed like a classic case of suicide to me,” says John Wagner, a Vietnam veteran, retired police lieutenant and longtime Custer buff.

Most Custer historians are just as emphatic that it wouldn’t have been in Custer’s nature to commit suicide. “I do not believe Custer committed suicide,” Michael Donahue says. “He was a soldier who had many close calls and he would have felt it a cowardly act. He also was right-handed and the bullet entered his left temple. Godfey looked for evidence of suicide and saw none. Custer’s younger brother Boston and nephew Harry were his responsibility. I believe they fled after George’s death. They were found 100 yards below Custer Hill dead and mutilated. Custer would never have allowed this if he had been alive and [he] could not have killed himself in front of them.”

One item is not in dispute: on the frontier, virtually all soldiers—including Custer—had an agonizing dread of being captured alive by Indians.

Before his death, Custer wrote about Indian torture in his autobiography and repeated the oft-mentioned refrain that officers “asserted they would never be taken alive by Indians.”

This pervasive belief, that the worst thing that could happen was to be captured alive by Indians, played into the collapse and rout of Custer’s men.

Add to the command’s tortured mindset the conditions on that hot June day, and it’s not hard to imagine that when Custer’s soldiers were overrun, they may have fallen victim to their own lurid indoctrination. And in that light, it is not hard to imagine that Custer either shot himself, or that his brother Tom, or someone else close to him, pulled the trigger.

The Killing Ground, Three Years Later

In 1879, Capt. George Sanderson and his 11th Infantry were sent out to the battlefield to clean it up. They were accompanied by a photographer, Stanley Morrow, and he captured this grisly scene of bones and equipment still strewn across the hills and gullies. In the foreground are a soldier’s boot soles. The Indians had no use for the soles and would cut off the bottoms and keep the tops for pouches or other uses. There is only one known earlier photo taken of Last Stand Hill in 1877 by Fouch. In this photo, the horses’ skulls still have hair. The photo is in a private collection.

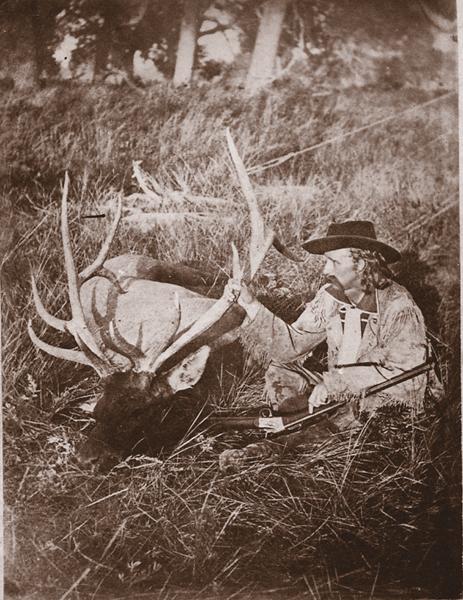

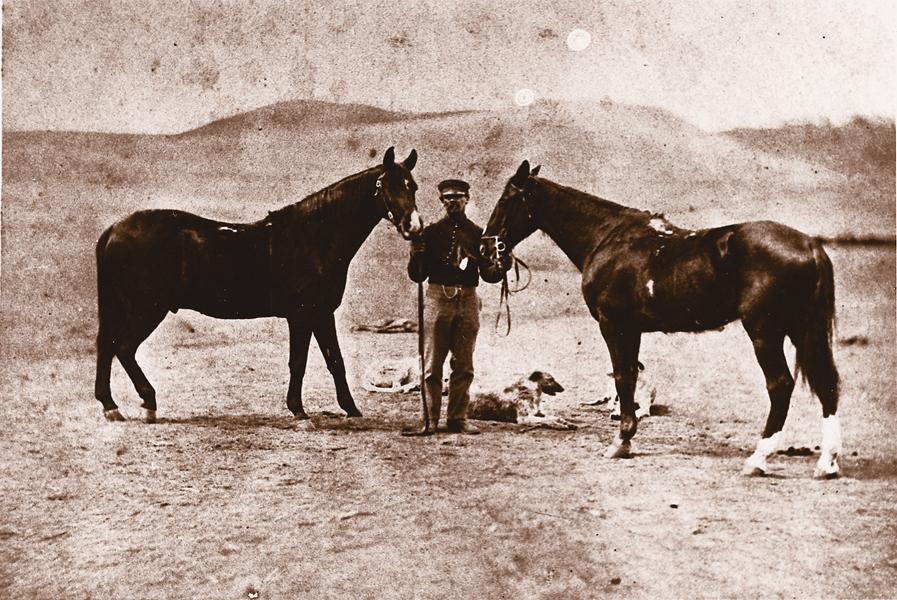

Custer’s Horses

Custer had two horses with him on the campaign: Vic (Victory) and Dandy. In battle, he rode Vic (right), who had a white blaze on his face and three white stockings. Historian Michael Donahue believes the Indians took Vic with them to Canada. In contrast, one field report states that Vic was found dead, 100-150 feet from Custer, and another says Vic was one of the dead horses making up the breastworks near where Custer died. Dandy (left)?was with the pack train and not only survived but was sent back to the Custer family.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

The total annihilation of George Armstrong Custer’s men did not end the fighting. The Sioux and Cheyenne warriors on Custer Hill immediately swarmed back to Maj. Marcus Reno’s and Capt. Frederick Benteen’s position and attacked them with everything they had. “The bullets fell like a perfect shower of hail,” remembered Lt. Francis Gibson. Benteen took control and rallied the men in their makeshift, horseshoe-shaped defensive line. In spite of Reno taking 73 more casualties (13 killed, 60 wounded), the surviving Seventh Cavalry soldiers held off the Indians for almost two days. Late on June 26, the Sioux and Cheyennes melted away and an eerie silence overtook the Little Bighorn Valley.

The Indians went their separate ways, with Sitting Bull and his band taking refuge in Canada. Crazy Horse and others headed toward the nearby Rosebud country and wherever else they could find buffalo.

A shocked nation demanded answers and results. The U.S. Army under Gen. Philip Sheridan redoubled its efforts to find and capture the Indians, but for the most part the soldiers were unsuccessful. General George Crook, however, did claim a victory over Chief American Horse and the Brule Sioux at the battle of Slim Buttes.

Recommended: Archaeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle by Richard A. Fox, Jr., published by University of Oklahoma Press; Custer in ‘76 edited by Kenneth Hammer, published by University of Oklahoma Press; The Custer Myth by Col. W.A. Graham, published by Stackpole Books; and Indian Views of the Custer Fight by Richard G. Hardorff, published by Arthur H. Clark Company

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– All illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

– True West Archives –

Custer had two horses with him on the campaign: Vic (Victory) and Dandy. In battle, he rode Vic (right), who had a white blaze on his face and three white stockings. Historian Michael Donahue believes the Indians took Vic with them to Canada. In contrast, one field report states that Vic was found dead, 100-150 feet from Custer, and another says Vic was one of the dead horses making up the breastworks near where Custer died. Dandy (left) was with the pack train and not only survived but was sent back to the Custer family.

In 1879, Capt. George Sanderson and his 11th Infantry were sent out to the battlefield to clean it up. They were accompanied by a photographer, Stanley Morrow, and he captured this grisly scene of bones and equipment still strewn across the hills and gullies. In the foreground are a soldier’s boot soles. The Indians had no use for the soles and would cut off the bottoms and keep the tops for pouches or other uses. There is only one known earlier photo taken of Last Stand Hill in 1877 by Fouch. In this photo, the horses’ skulls still have hair. The photo is in a private collection.