For anyone who rode the gunpowder trail, a six-shooter wasn’t the only weapon in his arsenal.

For anyone who rode the gunpowder trail, a six-shooter wasn’t the only weapon in his arsenal.

A gunfighter often had only one pull of the trigger to save his life in the days before Samuel Colt’s revolvers and Civil War-era repeating rifles. The 20 or more seconds it took to reload a single-shot percussion rifle could mean a permanent vacation in death valley.

Even after long-guns advanced to multi-shot pump, lever-action, bolt-action and double-barrel weapons during the last years of the Wild West, deadly mistakes were still often made in the confusion of a gun battle. And Texas Ranger George Lloyd knew that better than most.

When Indians attacked a group of Rangers during an 1881 gunfight, Lloyd hurriedly loaded his .44-40 caliber 1873 Winchester, accidentally slipping in a .45 caliber cartridge meant for his Colt revolver. The round’s larger size jammed the rifle.

Taking his knife from his pocket, Lloyd unscrewed and removed the side plates of his Winchester, then pried the stuck cartridge out of the receiver and replaced the side plates. After tightening the screws, he reloaded the rifle with the proper ammunition and resumed the fight.

How this ranger kept his nerve under such stress we’ll never know, but his story demon-strates why the lever-action became the rifle or carbine of choice for a number of frontiersmen. Many slab-sided repeaters were chambered for the same cartridges used in their owners’ six-shooters—an important factor in a life-or-death shoot-out. Luckily for Lloyd, his mistake didn’t cost him his life.

The lawless element also depended on the lever-action’s inter-changeable ammunition. Frank James said he used a brace of 1875 Remington revolvers in .44-40 caliber while riding with the James-Younger Gang “Because it carries exactly the same cartridge that a Winchester rifle does. The cartridges of one filled the chambers of the other…. There is no confusion here. When a man gets into a close, hot fight with a dozen men shooting at him all at once, he must have his ammunition all of the same kind.”

Yet, not all gunmen deemed it necessary for their rifles and six-guns to carry the same ammo. Until the turn of the 20th century, about 60 percent of Colt Single Action Army revolvers were manufactured in .45 caliber, which means many Peacemaker owners used that round in their handguns, despite their long-guns having a different chambering.

Lever-action gun packers

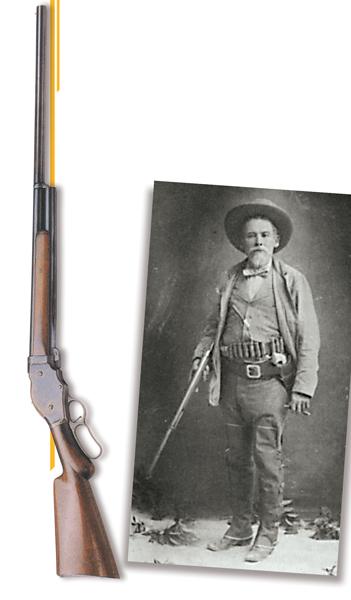

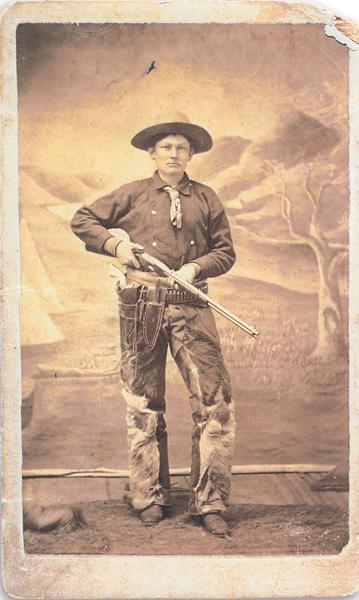

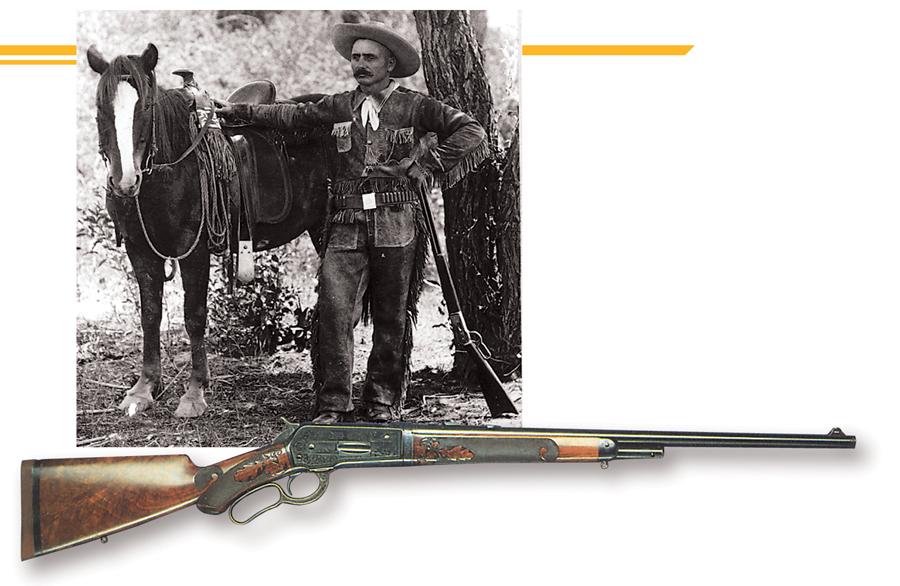

Lever-action guns had a comfortable heft, good accuracy and could be easily carried on horseback in a rifle scabbard.

Repeaters—the Henry, various model Winchesters, along with Marlins, the Spencer, Colt-Burgess, Whitney-Burgess, Whitney-Kennedy, Ballard, Evans and others—most often filled gunmen’s saddle scabbards during the late 19th century. By 1900, Savage had joined these ranks with the Model 1899.

Outlaw Bill Doolin carried an 1866 Winchester .44 the night he was killed by Deputy U.S. Marshal Heck Thomas.

Billy the Kid used a Whitney-Kennedy rifle, according to the Museum of the American West (formerly the Autry Museum of Western Heritage) in Los Angeles, California. Some historians think a .44-40 Model 1873 Winchester carbine was found among the Kid’s belongings by his adversary, Sheriff Pat Garrett, after the 21-year-old outlaw’s death.

The hired gunmen during the Johnson County War of 1892 packed 1886 Winchesters. Another fan of the ’86 Winchester was Al Sieber, chief of scouts during the Apache campaigns, although the model wasn’t available until after Geronimo surrendered in 1886. Bob Dalton was also packing an 1886 Winchester (in .38-56 caliber) when he was killed in the ill-fated raid on Coffeyville, Kansas, on October 5, 1892. During his days in the Dakotas, Theodore Roosevelt relied on a couple of Model 1876 and 1886 Winchesters. And Tom Horn, a scout and frontier regulator, carried an 1894 Winchester in .30-30 caliber during his final years on the range.

San Francisco detective James Hume—the man largely responsible for bringing California stage robber Black Bart to justice—was the proud owner of a Henry .44 caliber rimfire repeater, which now rests in the Wells Fargo collection in San Francisco, California.

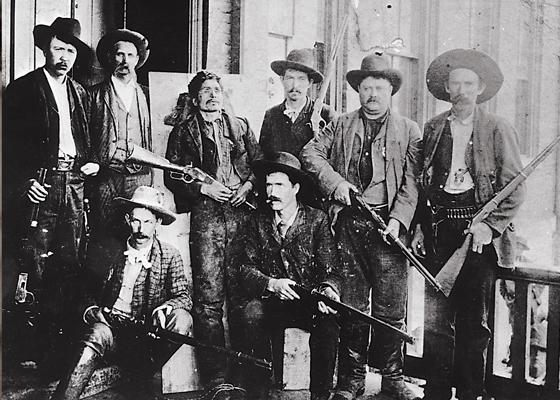

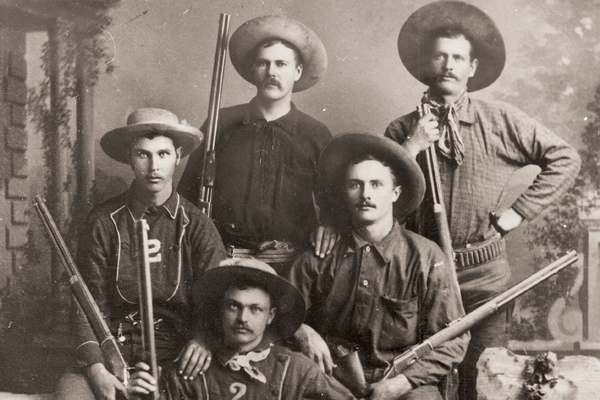

Lever-action rifles were also used by law enforcement organizations such as the Texas Rangers, who armed themselves with Winchester repeaters soon after the Model 1873 was introduced. The Texas lawmen favored the repeaters over the single-shot .50-70 Sharps carbines they had been issued—despite having to purchase the new Winchesters out of their own pay. When the Arizona Rangers formed in 1901, they adopted the Model 1895 Winchester in .30-40 Krag and carried it with a 51?2-inch barrel .45 Colt Peacemaker.

Guards on stagecoaches, trains and in express offices were usually issued lever guns. During the 1870s, some stagecoach companies equipped their coaches with a dozen Winchester rifles—along with plenty of spare ammunition, which was stored in pockets by the windows or “shooting ports.” In hostile country, such as the Dakota Territory, heavily armed coaches were frequently called “gunboats.”

Frontier wagon gun

Some frontiersmen preferred the single-shot longarm—even if only for hunting or sport where the gun’s greater power and longer range were an asset. Its excessive weight and size earned the rifle the label “wagon gun.” Others used single-shot carbines as saddle guns and sometimes these weapons saved the day for their owners.

When the Sioux attacked cattleman Nelson Story and about 20 of his drovers while they were driving a herd from Texas to Montana in 1866, the cowboys used Remington split-breech, rolling block carbines to drive the Indians off with minimal loss to the herd.

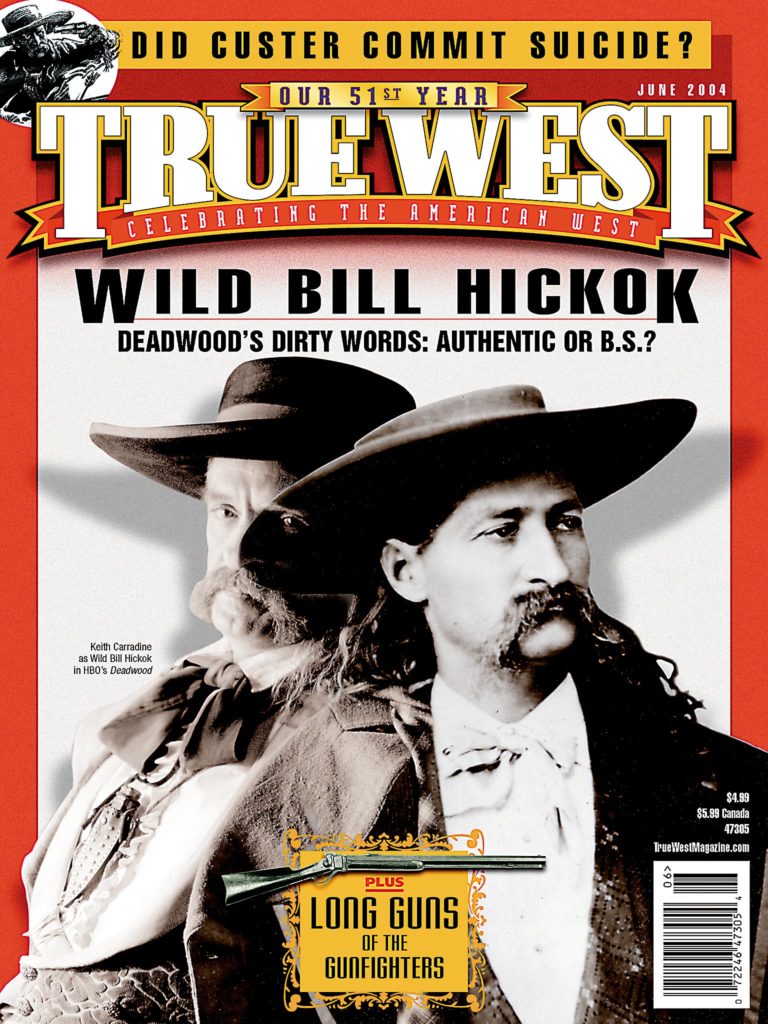

A single-shot may have also come in handy for James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. In one version of the July 12, 1861, gunfight in Rock Creek, Nebraska, he allegedly shot David McCanles with a half-stock, .56 caliber percussion Plains rifle (believed to have been made by Postley, Nelson & Company in Pennsylvania, says Hickok expert Joseph G. Rosa). Even though Hickok is thought to have been armed with an 1851 Colt Navy revolver, some historians think he used the big-bore long-gun so he could deliver a powerful and killing first shot.

Of all the single-shot rifles available on the frontier, the Sharps, Remington and Springfield were used most often, with the Ballard and Maynard placing close behind them. In the early days of lever-action rifles, before the repeaters offered power equal to the single-shots, these long-range weapons earned respect unequaled by any other firearm.

For many years, the Texas Rangers relied on Civil War-era percussion Sharps carbines that had been converted to take the .50-70 metallic cartridge. These short guns worked well on horseback. The heavy, larger Sharps rifles were first choice among buffalo hunters since they were often chambered for more robust cartridges. Despite their weight and size, these long-range guns —sometimes called the “shoots far gun” or the “Shoot today, kill tomorrow” gun by the Plains Indians — were coveted by gun-savvy frontiersmen of all breeds. Buffalo hunter Billy Dixon used a .50-90 Sharps — the so-called “Big Fifty” — to drop an Indian warrior from his horse at the astounding distance of 1,538 yards (about 7/8ths of a mile) during the Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle in June 1874.

Packing his Sharps .50 caliber rifle, frontiersman Richard Townshend engaged in a friendly shooting competition in 1870, while traveling through Colorado. A “spade-ace” playing card was nailed to a tree. Wolf, a Ute Indian warrior, fired Townshend’s Sharps and put three or four holes in the card. Townshend then shot it, hitting the nail and driving it into the tree. The brave was awestruck. “Wolf fairly fell upon my neck,” Townshend wrote. “‘Oh’ he sighed ‘you come with me. Come with me out on the Plains and kill Kiowas.’”

The Springfield rifle found its devotees as well. Army Ordnance issued Springfields to railroad and telegraph crews for hunting and defense. Outfits that worked in Indian country, such as the Union Pacific Railroad, Kansas Pacific Railroad and Western Union Telegraph Co., were armed with Springfield “needle guns,” as the early Allin conversion trapdoor rifles were then called.

During Buffalo Bill Cody’s scouting and hunting years, he carried a .50-70 caliber Allin conversion, which he affectionately referred to as “Lucretia Borgia” because he considered his one-shooter not only beautiful but also deadly.

Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens of Apache County, Arizona Territory, relied on a .45-70 Springfield officer’s rifle, whereas notorious Texas bad man John Wesley Hardin once set aside his six-guns for a “needle gun” when a posse pursued him, as he recounted in his autobiography.

“Street howitzer”

If any longarm is associated with the professional Old West gunfighter, it is undoubtedly the shotgun. Regardless of whether the weapon was a double-barrel (which was the most commonly used smoothbore), single-shot, pump or a lever-action, the scattergun’s advantages in a shoot-out were so great that it was carried at one time or another by a legion of men on both sides of the law.

Billy the Kid used a shotgun to kill guard Robert Olinger during the Kid’s escape from the Lincoln County Jail. John Wesley Hardin employed a scattergun on several occasions throughout his early career as a shootist. Arizona’s Cochise County Sheriff John H. Slaughter relied heavily on his 12-gauge sawed-off Remington shotgun. California stage robber Charles “Black Bart” Bolton bluffed his way through a series of holdups with his double-barrel—though he later acknowledged that his shotgun was never loaded since he didn’t want to hurt anyone.

Although gunslinger John H. “Doc” Holliday preferred using his revolvers, he reportedly carried a 10-gauge Meteor. (This type of shotgun was also used by Porter Rockwell, the infamous Mormon “Avenger.”) Holliday’s “street howitzer” was cropped off short enough so he could carry it under his arm in a leather sling. In his most famous gunfight (near Tombstone, Arizona’s O.K. Corral in 1881), Holliday opted for the double-barrel shotgun that Virgil Earp had borrowed from a Wells Fargo office earlier that day. When lead started flying, Holliday fired a blast of pellets into Tom McLaury, killing him on the spot.

After Wyatt Earp’s brother Morgan was murdered the following March, Wyatt pursued the chief suspect, Frank Stillwell, catching him on March 20, 1882, at a train station in Tucson, Arizona. During a scuffle between the two men, Stillwell pushed Earp’s shotgun aside by grabbing the barrels, but the scattergun discharged, wounding the fugitive. Earp and his confederates then vengefully finished him off in a hail of bullets.

The scattergun was ideal for nighttime gunfights because its shot pattern compensated for less than pinpoint accurate aim. On the moonlit night of August 24, 1896, peace officer Heck Thomas and his posse confronted bad man Bill Doolin and ordered him to surrender. It’s unknown whether Doolin got a shot off before the posse opened fire, killing Doolin with a blast from a double-barrel 12 gauge. The outlaw was hit with 21 buckshot.

Besides being a favorite in shoot-outs, the scattergun is more famous as a “crowd tamer.” The sight of a lawman’s double-barrel shotgun was usually all the persuasion a peace officer needed. As one Bodie, California, stagecoach driver put it, “I have had a six-shooter pulled on me from across a faro table, I have proved that the hilt of a dirk can’t go between two of my ribs … but I was never really surprised until I looked down the muzzle of a double-barreled shotgun in the hands of a road agent. Why, my friend, the mouth of the Sutro tunnel is like a nail hole in the Palace Hotel compared to a shotgun.”

In the hands of good and evil

Long-guns often came into deadly play during the raucous years of the Wild West. Teamed with six-guns and bravado, longarms helped clear the trails and settle the West. In the hands of good and evil, they both enforced and broke the laws of the frontier, all the while leaving in their smoky wake the legends and lore of the gunfighters of the Old West.

Phil Spangenberger writes for Guns & Ammo magazine and is a character actor and Hollywood gun coach. His column, Shooting from the Hip, appears in every issue of True West.

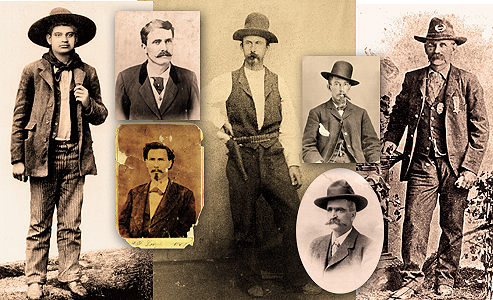

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center –

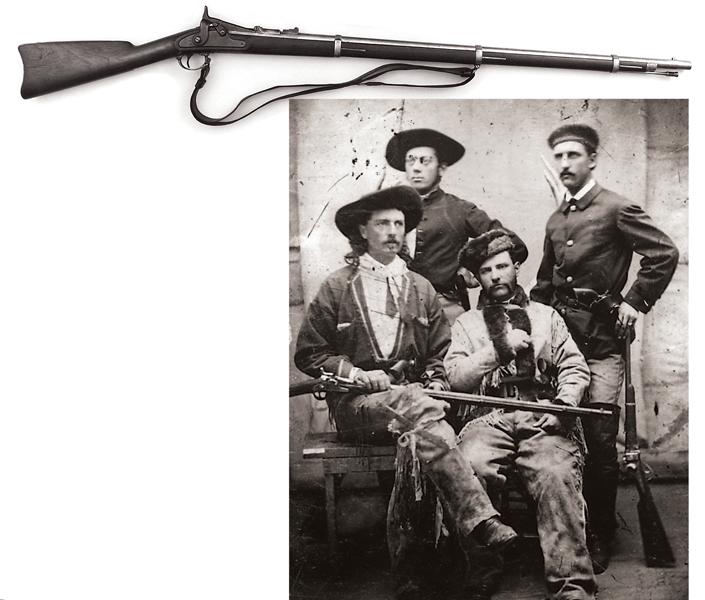

– Sharps photo True West Archives; Cowboy photo courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

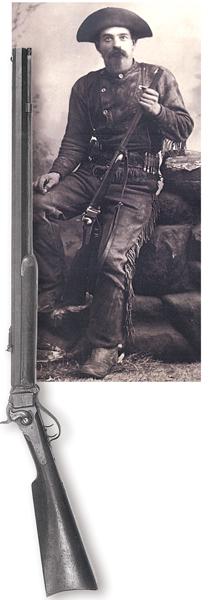

– Courtesy Nick D’Amelio –<br/?

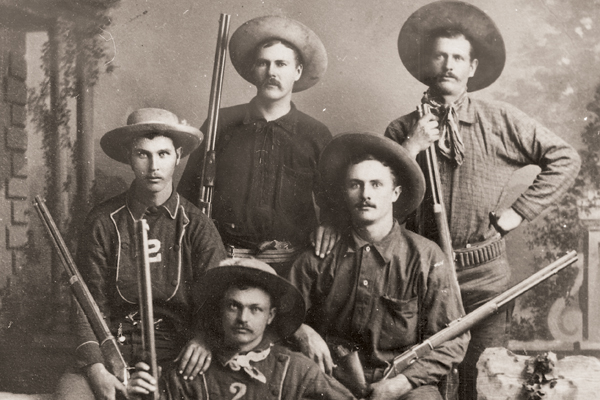

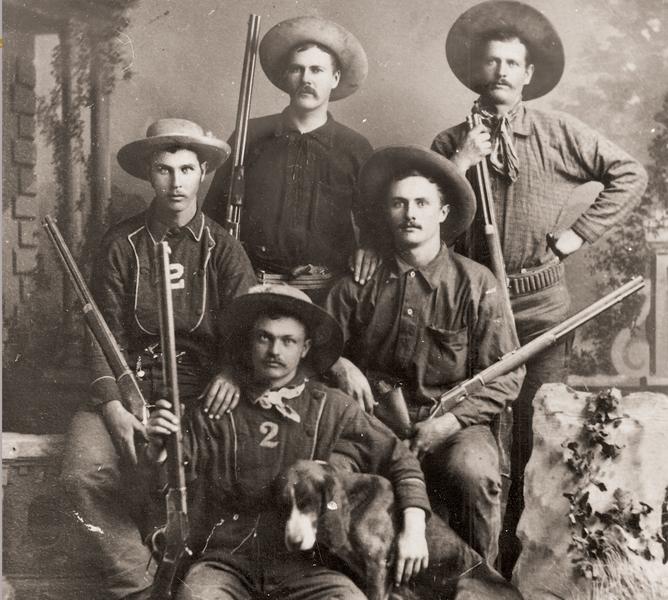

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Pat Garrett photo courtesy Robert G. McCubbin; 1873 Winchester photo True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger –