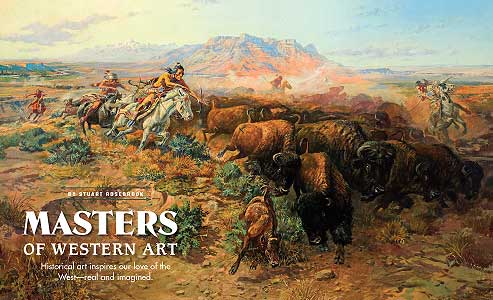

Western historical art has two great masters to whom all later artists are compared: Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. The peers have their champions and their detractors, but whether you favor the “Montana Cowboy” over the “New York Dude,” or vice versa, the fact is these two American artists stand at the foundation of 135 years of Western American art.

Western historical art has two great masters to whom all later artists are compared: Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell. The peers have their champions and their detractors, but whether you favor the “Montana Cowboy” over the “New York Dude,” or vice versa, the fact is these two American artists stand at the foundation of 135 years of Western American art.

Interestingly, both Remington and Russell were from the East, but Russell left New Jersey at age 16 in 1880 never to return, whereas Remington left Yale for Montana at age 20 in 1881, but traveled back-and-forth from the West to New York for his marriage and career.

From the great settlement era and the end of the Indian wars in the West of the 1880s until Remington’s death in 1909, and Russell’s in 1926, the artists’ paintings, sculptures and illustrations captured the soul of the changing frontier. Following in the artistic footsteps of George Catlin, George Caleb Bingham and Alfred Miller, Remington and Russell benefited from traditional exhibitions in salons and galleries, and from the glorious new era of book, magazine and newspaper publishing. Yet, as the two became renowned internationally for their art, the imaginations of a new set of masters—filmmakers—were inspired by the soulful realism of Russell’s and Remington’s art.

In the 1920s, Russell actually spent a great deal of time in Southern California and became a close friend of many Hollywood producers, directors and actors, including John Ford, Will Rogers and Harry Carey Sr., who built the Montana artist an adobe cabin at his Los Angeles-

area ranch.

In 1926, before Russell died, he was famous for saying, “Any man that can make a living doing what he likes is lucky, and I’m that.” He had lived long enough to experience the development of the West from a frontier society of homesteads and range wars to dude ranches and subdivisions. It can only be speculated what Remington would have created as an artist if he had lived longer (he was only 48 when he died of complications from appendicitis), but his legacy can be seen at museums and galleries across the United States, as well as in Western film and television.

Ford, who became a friend of Russell’s through Carey, was greatly inspired by the art of Russell, Remington and Charles Schreyvogel, as were many others in Hollywood. Western artists strongly influenced film directors and their production designers, from the earliest silent horse-operas to the most recent big-budget Western films and television series. In fact, studios and producers have hired hundreds of artists as storyboard illustrators to conceptualize the look of a production. Just watch the films Stagecoach, Red River, Shane, The Searchers, Monte Walsh, El Dorado, Tombstone and, most recently, the television series Hell on Wheels to witness how Western art influenced the production design and costuming. If you tour the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, you will quickly realize the great impact of Remington and Russell on our imagined memory of the West. As you pause at each painting, you will gain an understanding of how the great artists’ palettes and colorful interpretations of the West have influenced generations of Western artists—and artists who interpret words and art onto film. Two films, Monte Walsh and El Dorado, actually used the classic Western art of Remington, Russell and Olaf Wieghorst, respectively, in their opening credits—an homage to the roots of the genre.

In honor of the masters of Western art, Charles Russell and Frederic Remington, who nearly 135 years ago traveled West in search of their destinies, True West celebrates two centuries of Western historical art by featuring a retrospective of works by the two masters and a portfolio of works by artists who also have created and inspired our real and imagined history of the American West.

Click on the image, enjoy our sideshow of the Masters of Western Art.

Photo Gallery

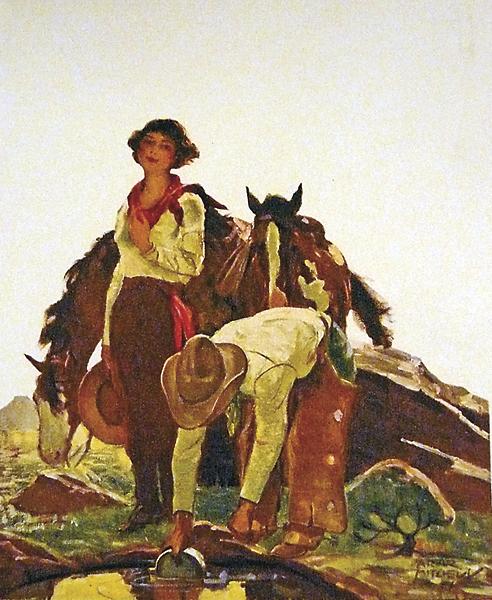

A.R. Mitchell shares the legacy of Western art with Russell and Remington. All of them supported their careers through highly evocative and popular illustrations of the 19th-century West—like Mitchell’s undated True Love—for magazines, newspapers and books.

– Courtesy A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art, Trinidad, CO –

Albert Bierstadt, whose epic landscape paintings of the West were only challenged later in size and scope by Thomas Moran, was inspired to paint Landscape with Indians after his first trek West with surveyor Frederick W. Lander in 1859.

– Autry National Center, Los Angeles, CA, 88.108.13 –

Alfred Jacob Miller’s portraits of American Western archetypes—including Louis-Rocky Mountain Trapper, ca. 1855—were similar to works by George Catlin, Karl Bodmer and Charles Deas. Miller’s portraits provided a model to a generation of artists who followed him into the West, and a historical record of the Mountain Man era.

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wy, 36.64 –

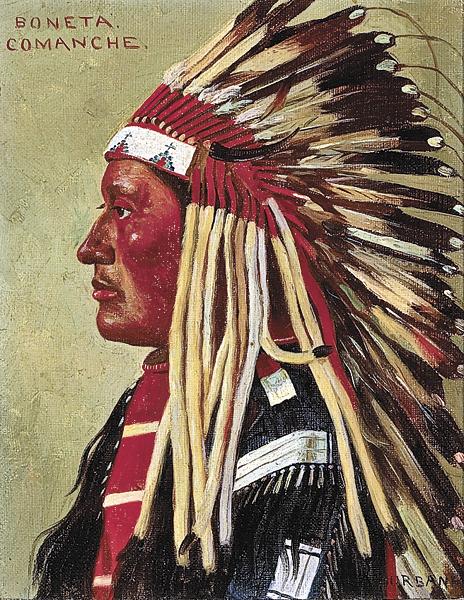

Elbridge Ayer Burbank, the greatest traveling

Charles Deas greatly admired George Catlin, and when the young Deas went West to pursue his career as an artist, he lived among the tribes like Catlin had. Deas painted American Indians and fur trappers, including this iconic 1844 oil painting, Long Jakes:

Charles Russell’s paintings of the West emphatically express the pathos and empathy he had for the American Indians of Montana as in his poignant oil titled Her Heart is on the Ground.

– Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, 0137.907 –

In the 1920s, Charles Russell spent much of his time in Hollywood with actors and directors, including John Ford, whose Western films would reflect the influence of Russell’s paintings of the noble American Indian, such as his 1921 oil titled In the Enemy’s Country.

– Courtesy Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO, 1991.751 –

Charles Russell’s legacy as a master of numerous artistic styles and mediums gave him an opportunity to create different moods and softer light in his noble rendering of Plains Indian culture in his 1894-95 watercolor The Returning Herd.

– Autry National Center, Los Angeles, CA, 88. 108.35 –

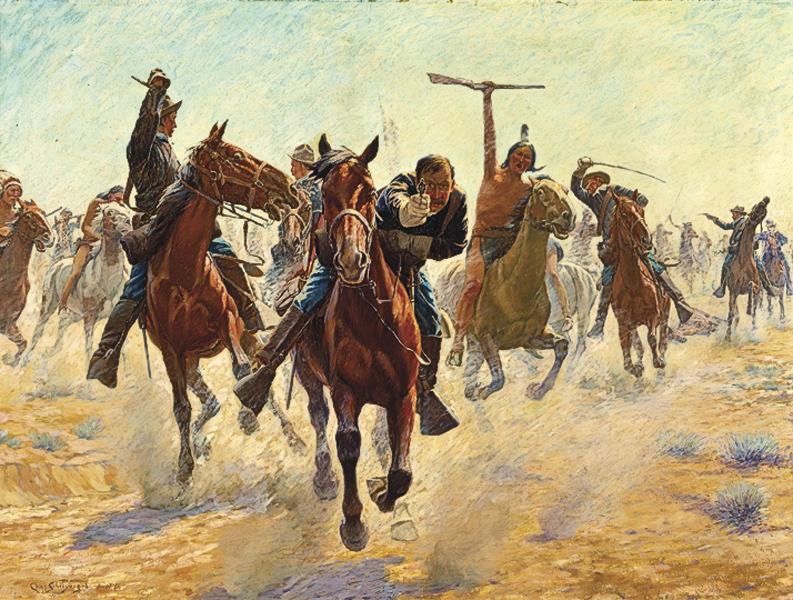

Except Remington and Russell, no other artist had greater influence on Western film director John Ford than Charles Schreyvogel, who in the 1890s and 1900s painted some of the most popular, realistic action paintings of the American Indian wars, including his undated oil painting Breaking Through the Line.

– Courtesy of Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, 0127-1235 –

Charlie Dye, who grew up as a cowboy and admired Charles Russell’s work, had a successful career as an illustrator before he moved to Sedona, Arizona, in 1962. There he helped found the Cowboy Artists of America, and painted what he knew best, including this undated oil painting, Cullin’ the Herd.

– Courtesy Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Wickenburg, AZ –

As America’s greatest, working-cowboy artist, Charles Russell painted from a perspective that his peer Frederic Remington could never claim—a cowboy’s harsh reality of sudden death when working cattle, as he vividly depicts in his 1897 oil titled Incident near Square Butte.

– Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas, 31.11.9 –

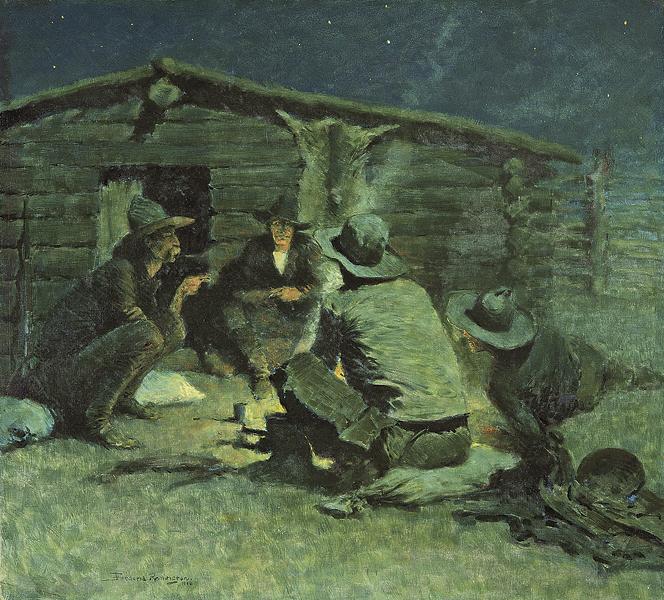

Frank Tenney Johnson, who camped and painted with Charles Russell in Montana in 1912, became well-known for his mastery of night scenes, highly evocative of Frederic Remington’s use of darkness and light as shown in The Pony Express.

– Courtesy Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, OK, 0127.1088 –

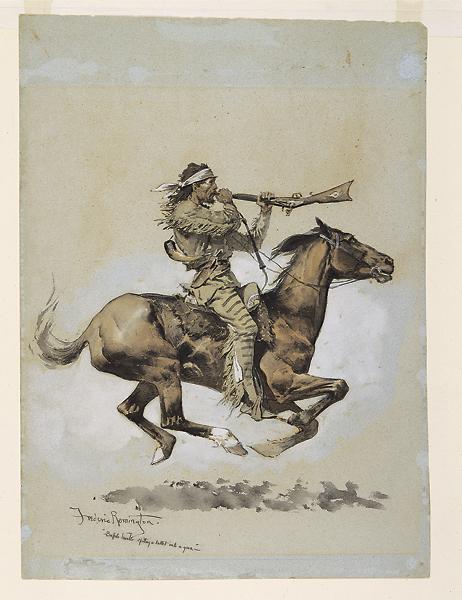

Frederic Remington’s illustrations and paintings of horse and rider in motion are one of his greatest legacies as an artist of the Old West, including his unique Buffalo Hunter Spitting a Bullet into a Gun, an 1892 watercolor.

– Courtesy Frederick Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY –

Frederic Remington, who was influenced by the French impressionists, had a brilliant ability to capture the harsh, nearly overpowering light of the Western summer sun and sky, as seen in his 1905 oil painting Only Alkalai Water.

– Courtesy Autry National Center, Los Angeles, CA, 88.108.21 –

Frederic Remington’s reputation as a great American painter, a legacy solidified in the impressionistic style he adopted in his last years, is reflected in his final painting, Untitled (possibly The Cigarette), which he was working on in his Connecticut studio in 1909.

– Courtesy Frederick Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY –

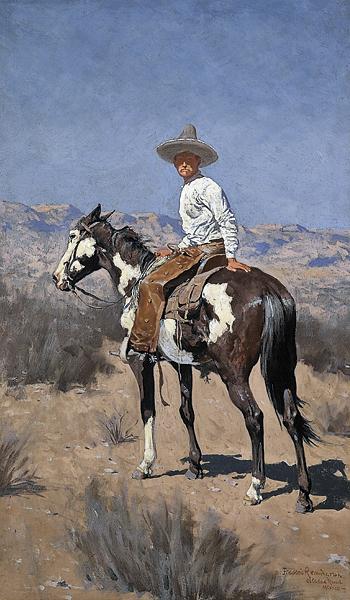

Frederic Remington’s 1890 oil painting, Vaquero, brilliantly demonstrates his ability to capture the ruggedness of the Western landscape, the desert summer sun and sky, and an archetype character of the West in a single, historic masterpiece.

– Courtesy Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Wickenburg, AZ –

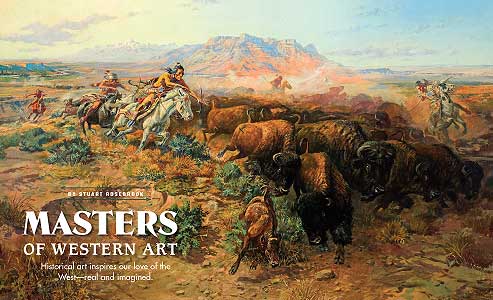

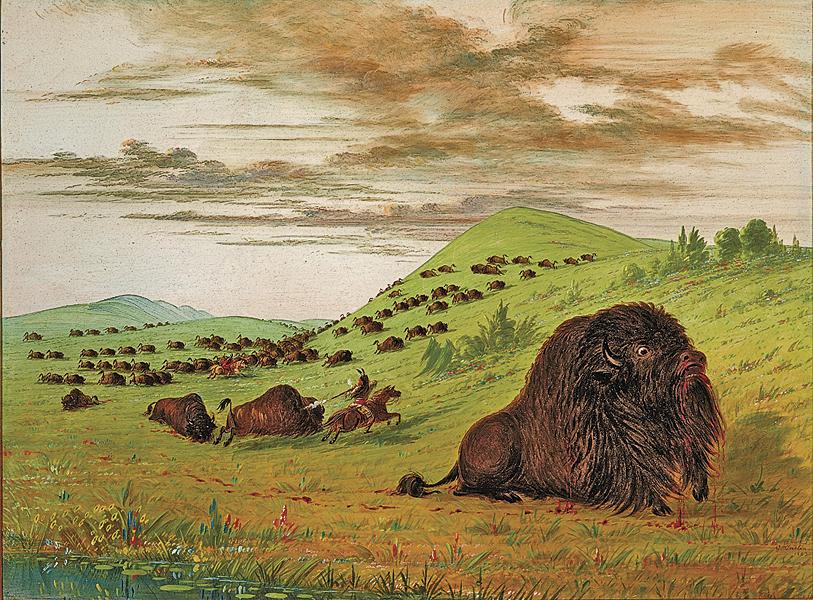

An early master of Western American art, George Catlin’s advocacy for the plight of the American Indian and his artwork, including his 1863 Buffalo Hunt, greatly influenced his peers and future artists such as Russell and Remington.

– Courtesy Autry National Center, Los Angeles, CA, 88.108.7 –

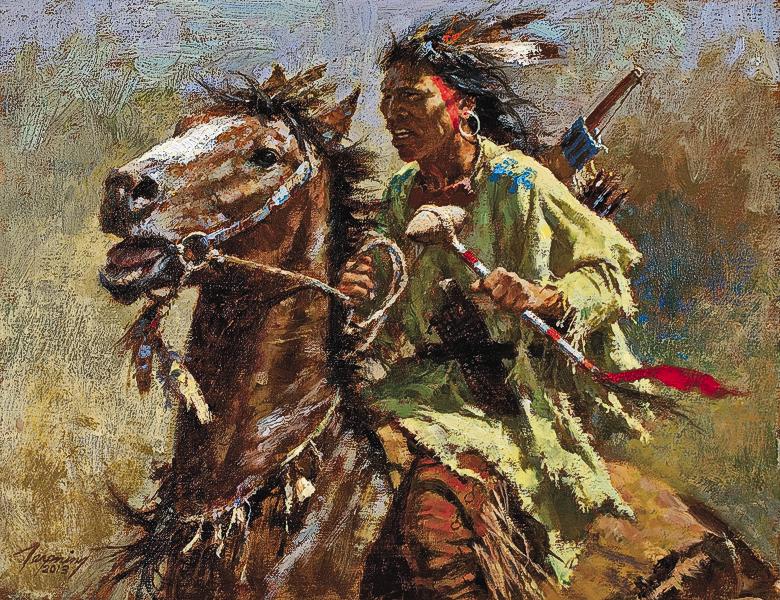

Howard Terpning began his career as a commercial illustrator as did Frederic Remington, but in 1974 Terpning re-focused his career on painting the historical American West. His portfolio of Plains Indian art is comparable to the early masters of Western art, and includes his 2014 oil titled War Chief.

– Courtesy Settlers West Galleries, Tucson, AZ –

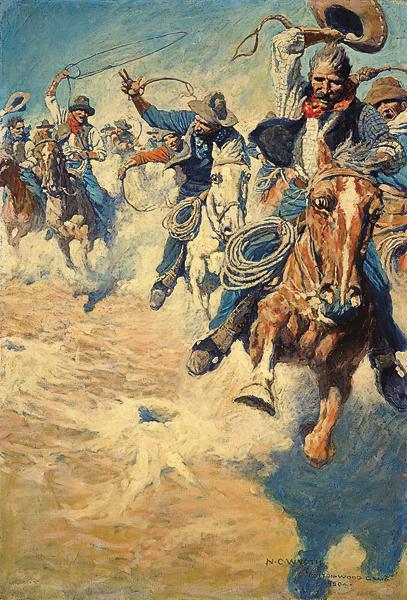

Newell Convers “N.C.” Wyeth, who began his career in the first decade of the 20th century under the tutelage of the great illustrator-artist Howard Pyle, was strongly influenced by Remington’s style of action and color, as demonstrated in Wyeth’s 1904-05 oil The Wild, Spectacular Race for Dinner.

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wy, 44.83 –

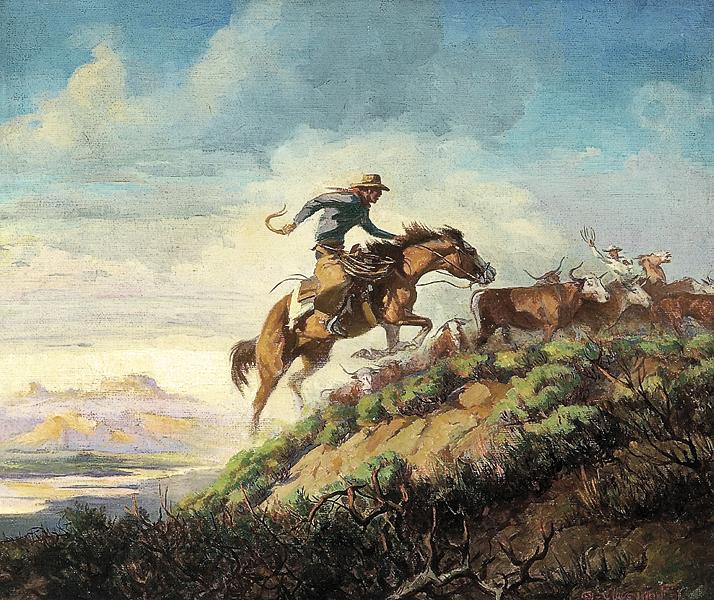

In the mid-20th century, Danish-born horseman and self-taught artist Olaf Wieghorst emerged as a popular heir to the Remington and Russell style of historical art through his passion for painting Western history, horses, Indians and the American cowboy, as illustrated in his 1941 painting Rounding Up the Herd.

– Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Wickenburg, AZ –

Like Charles Schreyvogel and Frederic Remington, award-winning Western artist Sherry Blanchard Stuart’s art is inspired by the classic horsemanship of the 19th-century American cavalryman, as seen in her 2014 oil painting Fort Snelling Drills.

– Courtesy Open Range Gallery, Scottsdale, AZ –

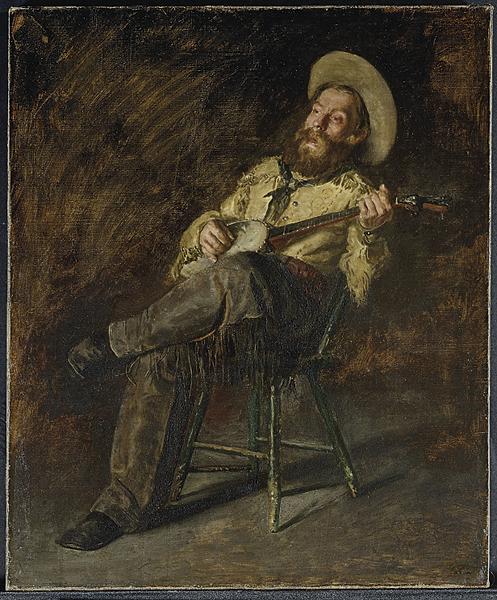

American artist Thomas Eakins, a peer of Russell and Remington and renowned for his style of realism and motion in his art, painted numerous interior, seated portraits in low light, including the very Western banjo player from 1892, Cowboy Singing.

– Courtesy Denver Art Museum and the American Museum of Western Art—The Anschutz Collection, Denver, CO, 2008.491 –