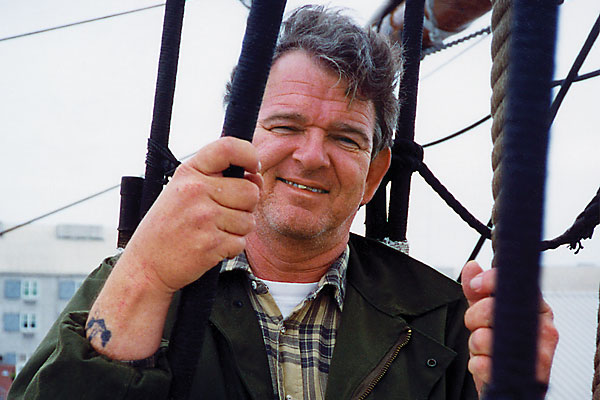

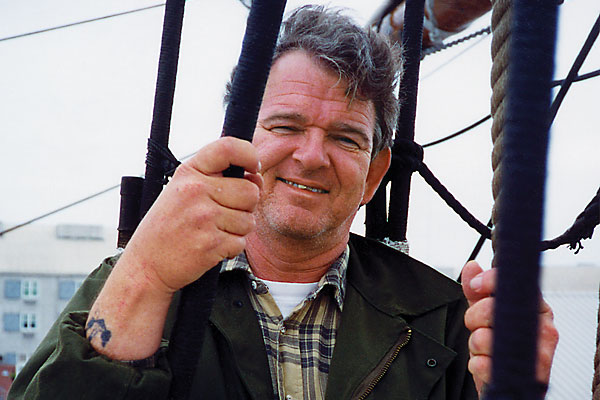

Sandwiched between his first writing and editing jobs with the Valley Morning Star in Harlingen, Texas, and his current gig as a history professor at South Texas College in McAllen, Texas, Charles M. Robinson III has written of sea stories and classic cars, but mainly has followed the men of the frontier army from Texas and Arizona to the Northern Plains.

Sandwiched between his first writing and editing jobs with the Valley Morning Star in Harlingen, Texas, and his current gig as a history professor at South Texas College in McAllen, Texas, Charles M. Robinson III has written of sea stories and classic cars, but mainly has followed the men of the frontier army from Texas and Arizona to the Northern Plains.

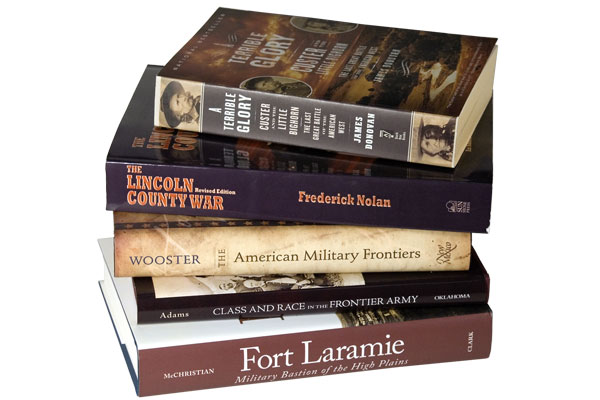

Subjects have included George Crook, Ranald Mackenzie and George Armstrong Custer. His last three books—plus the next several awaiting his attention—involve the diaries of John Gregory Bourke, aide-de-camp to Crook and unofficial “press agent.” Robinson is completing volume four of Bourke’s diaries—that includes the years 1872-96—-and figures he is halfway done with the project. His military histories include A Good Year to Die: The Story of the Great Sioux War; General Crook and the Western Frontier and Bad Hand: A Biography of General Ranald S. Mackenzie.

TW: You have written about Crook, Mackenzie and Bourke. Who is the more interesting character?

CMR: Each was interesting in his own way, and I really can’t choose between them. All three were fascinating. They served together on the Northern Plains. They had the same opinions that Indians, once pacified, deserved a chance to make it on their own. And they all shared a loathing of Nelson Miles.

TW: They all had strengths and weaknesses?

CMR: I think Mackenzie’s great asset was his tactical genius; he understood cavalry as did a few other American officers. Unlike so many of his peers, he also realized that Indians did not study the West Point manual and adapted to their mode of fighting. His weakness was his mental instability.

Crook showed great tactical skill in the Northwest and in Arizona, and spent the remainder of his career resting on those laurels. His performance on the Northern Plains was abysmal, as Generals William T. Sherman and Phil Sheridan both realized. He came very close to being annihilated at the Rosebud, yet he insisted it was a victory. The low point probably was the Horse Meat March that ruined both men and animals. His greatness comes in his efforts on behalf of the Indians. Undoubtedly, he was behind the suit that Standing Bear filed against the federal government, and which was a turning point in Indian rights.

Bourke was the scholar and diarist, whose writings of campaigns and investigations of Indian life and culture have been invaluable to researchers for more than a century. His weakness was his loyalty to Crook, and he is largely responsible for Crook’s undeserved image as the country’s self-effacing premiere Indian fighter.

TW: How important was the press in developing Crook’s image?

CMR: Crook utilized the press in the same manner as Douglas MacArthur of a later generation. Friendly correspondents achieved an “insider” status. Unfriendly reporters were ostracized. Crook did his best to make certain that all official reports and correspondents’ dispatches portrayed him in the best possible light.

TW: How did Bourke contribute to that?

CMR: Bourke was Crook’s unofficial press agent, making certain that official reports looked good and, I suspect, exercising some influence over what the correspondents wrote. As the scholar of Crook’s staff, he helped formulate some of the general’s ideas and gave intellectual justification to notions Crook already had.

TW: When Crook allowed Joe Wasson to accompany him on expeditions, he was breaking new ground with a reporter, wasn’t he?

CMR: Not only did Crook break ground, but so did Wasson. Up until that time, very little, if anything, about Indian campaigns was written by correspondents in the field. Instead, editors and reporters sitting in offices took whatever information they could obtain, generally from government reports or rumor, and constructed a story around it. Very often, it was almost total fabrication. Wasson changed all that by covering an Indian campaign from the scene. His great flaw was that he absolutely hated Indians, and his dispatches reflected that hatred.

In addition to his military titles, Robinson has authored The Buffalo Hunters, an account of those who contributed to the demise of the immense herds, The Men Who Wear the Star: The Story of the Texas Rangers, plus he’s written about both pioneer settlers and Indian people in The Frontier World of Fort Griffin: The Life and Death of a Western Town; The Indian Trial: The Complete Story of the Warren Wagon Train Massacre and the Fall of the Kiowa Nation; and Satanta: The Life and Death of a War Chief.