Those who imagine the Western to be a fundamentally American art form like jazz or comic books would do well to take a closer look at our cousins down under.

Those who imagine the Western to be a fundamentally American art form like jazz or comic books would do well to take a closer look at our cousins down under.

Australia’s Wild West was, in many respects, exactly like our own and at precisely the same time. We had our outlaws, they had their bushrangers; both of us filched real estate, carried guns, wore big hats, indulged our vices and spat attitude.

And remember when Butch Cassidy was trying to talk the Sundance Kid into escaping to Australia? “They got horses in Australia,” he said, “and they got thousands of mountains you can hide out in.” Seems like that’s about all a wild buckaroo needed back then.

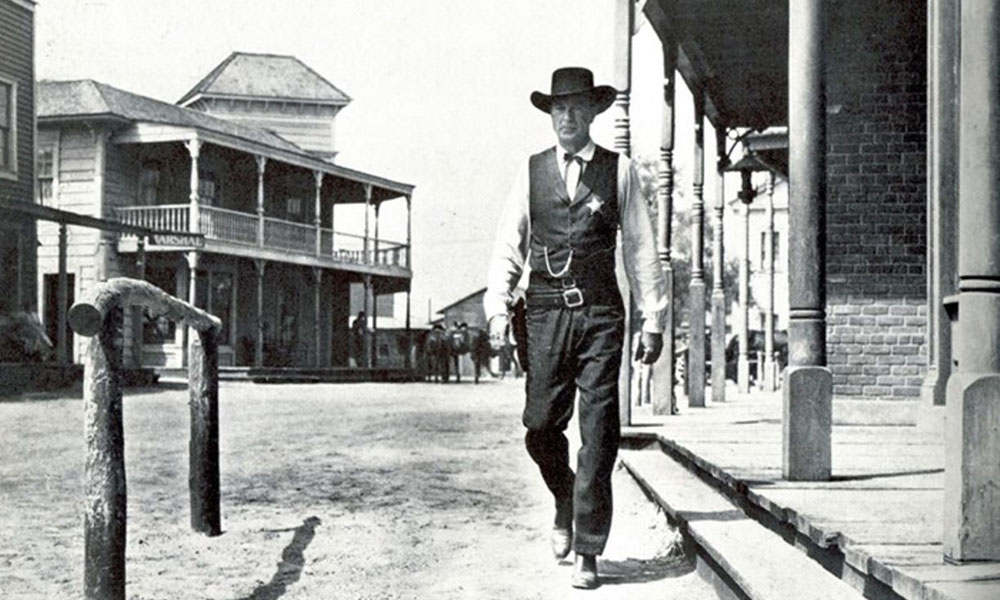

When the West as such quietly closed its shutters, it came back to life a few years later in the movies, and America could honestly claim The Great Train Robbery (1903), which was 12 minutes long, to be the first actual Western motion picture, even though it was shot in New Jersey.

But the first full-length feature film in cinema history was an Australian Western, Ned Kelly and His Gang, which drew packed houses throughout Oz in 1906. It even had the honor of being banned for its sympathetic portrayal of the bad guys. Sound familiar?

Exactly one century later, the best Western to come along in years is a quasi-mystical Australian drama that is dark, violent and literate, part Spaghetti Western, part Sam Shepard.

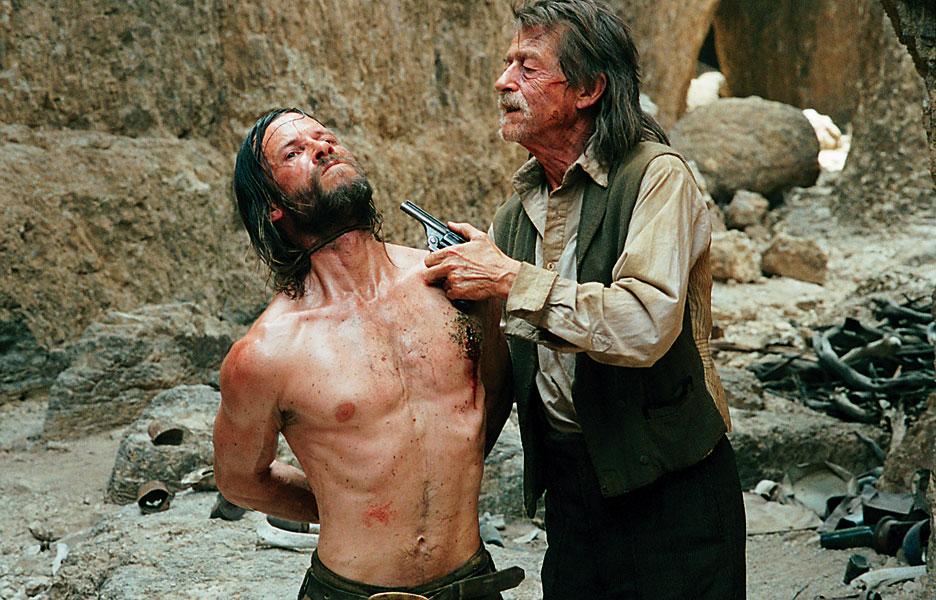

Set in the outback and featuring an international cast, The Proposition stars Guy Pearce, Danny Huston and Richard Wilson as three Irish brothers on the run from Captain Stanley (Ray Winstone), the head of the regional police, who is determined to make his small section of Australia safe for his delicate wife, Martha (Emily Watson).

This is not a simple task, and early in the film, while looking out across the desolate prairie, he mutters, “Australia. What fresh hell is this?” (It would be churlish to point out that Captain Stanley is actually quoting writer Dorothy Parker a decade before she was born.)

Following a bloody siege that opens the picture, Stanley captures two of the three Burns brothers, perpetrators of an unforgivably vicious crime, and promises to hang the youngest of the siblings, Mike (Wilson), on Christmas day unless Charlie (Pearce) hunts down and kills his older brother Arthur (Huston). That is, in fact, the proposition of the title, and it manages to make Stanley and his wife very unpopular among the locals.

Arthur, meantime, is living in a cave with a woman, a lackey and a dog, and, like Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, he has achieved a kind of lunatic awareness so profound that the aboriginals believe him to be an invulnerable shapeshifter.

“Dog man,” reports an interpreter, querying a group of shackled natives. “Never sleep. Cannot catch him. Cannot kill him. He is dog.”

Once we meet Arthur, it’s clear that he’s charming, brilliant and a vicious psychopath, the outback equivalent of Judge Holden in Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 novel Blood Meridian.

It’s clear at this point that The Proposition is not designed along the lines of a Turner Western or some kind of retooled collection of classic leathery tropes. But the movie has at its heart much the same kind of otherworldly tone found in a wide number of Australian films, dating at least as far back as Walkabout (1971), and running through many of the movies of Australian director Peter Weir, including Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Witness (1985) and even Master and Commander (2003).

Certainly one of the more interesting angles on The Proposition is the way it’s been received at home, pulling in a total of 23 award nominations from three different Australian film organizations, and winning 10 of them, including an IF Best Feature Film award, which is somewhat akin to America’s People’s Choice awards.

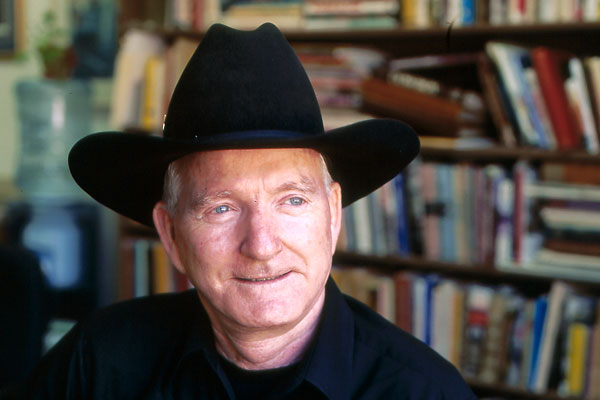

Perhaps one of the key elements that brought it to the attention of the Australian public is the fact that the script was written—in three weeks, he claims—by Nick Cave, who is something of a cult music star in America but has a much larger profile in his native Australia.

Cave is a prolific singer and songwriter who’s straddled several genres—Punk, Psychobilly, Folk and Goth—since he entered the scene with a band called The Boys Next Door in 1977, which became The Birthday Party three years later. He moved to Berlin in the mid-80s and formed The Bad Seeds, but he’s never been very far removed from his Australian origins. His 1996 album Murder Ballads, which describes the disc perfectly, foreshadows the ideas and sensibility that came to play in The Proposition.

Cave and his Bad Seeds cohort Warren Ellis also composed the soundtrack for the film, which is eerie and unsettling.

But Cave’s main collaborator on the picture is Director John Hillcoat, who came to the attention of the public after a series of well received music videos for Cave, INXS, Crowded House, Robert Plant and others, and a prison drama, also involving Cave, called Ghosts…of the Civil Dead (1988).

In the press notes, Hillcoat admits he’d been waiting to make a Western for some time. Finally, after a number of delays, he pressured Cave into writing the script.

“It’s something I’ve been obsessed about for a long time,” he says, “ever since my days at film school. I’ve always been interested in the Western as a genre

and wanted to explore that and stretch it into another context, setting it in an Australian landscape.”

The crew and cast traveled to Winton, a town deep in the central northeast of the continent, and largely known for having been the place where, in 1895, A.B. “Banjo” Paterson wrote the tragic tune “Waltzing Matilda,” which eventually became the unofficial Australian anthem. Winton’s other claim to fame, prior to The Proposition, was its dinosaur fossils.

“We had to learn to eat flies, and to avoid eating flies” says Pearce, about working in Winston. “And we had to get used to wearing several layers of clothing in 120-degree weather.”

If there’s one significant difference between the American Western and its Australian counterpart, it’s that on this continent, the genre is largely confined to the land west of the Mississippi, whereas in Australia, it’s all considered to be the West.

Photo Gallery

Charlie Burns (Guy Pearce) is a bushranger locked in a moral purgatory where he’s obliged to kill one brother to save another.

– All images courtesy First Look Pictures –