Peanut shells litter the National Western Stock Show and Rodeo’s “green room.” A minister prays with a young cowboy, preparing him for his bull ride. There’s a card game at one of the tables, while other cowboys work telephones and check gear.

Peanut shells litter the National Western Stock Show and Rodeo’s “green room.” A minister prays with a young cowboy, preparing him for his bull ride. There’s a card game at one of the tables, while other cowboys work telephones and check gear.

It’s a scene that could be straight out of 1955 instead of 2005, except for a few details: the obnoxious laser show and rock ’n’ roll blasting inside the arena … cell phones instead of rotary pay phones … hockey masks and flak jackets for bull riders … and a banner advertising, uh, massage therapy?

Oh, yeah, and money. Lots more money.

What’s the biggest change in rodeo since the 1950s? “It starts with an ‘M’ and ends with a ‘Y’ and they call it money,” says Jim Shoulders, all-around champion in 1949 and 1956-59.

In 1959, the Rodeo Cowboys Association (which became the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association in 1974) awarded $3,192,745 in prize money. That figure had rocketed to $35,532,631 in 2004.

“When I was a kid,” Shoulders says, “folks told you if you wanted to make some money, you needed to become a professional person, a doctor or lawyer or somethin’. Now, they say get into sports. I never heard of a doctor gettin’ out of medical school and signin’ a multimillion-dollar contract. I thought I was rich if I won a $40 go-round.”

Money, of course, has grown in all sports. When Lee Petty won NASCAR’s first Daytona 500 in 1959, his prize was $19,050. That’s pocket change for 2005 Daytona winner Jeff Gordon and his $1,497,150 paycheck.

Besides, let Neal Gay, who rodeoed in the late ’40s and early ’50s, put all that dough in perspective. “I’d win $12,000, $15,000 a year, and that was about it,” says Gay, who founded suburban Dallas’ Mesquite Championship Rodeo in 1957. “But you could buy gasoline for 20 cents a gallon and a new pickup for $995, so it’s not a whole lot different than it used to be.”

Here’s a sport that got its start in the West, depending on where you are and who you ask, in Arizona or Texas in the 1880s, Colorado in the 1860s or New Mexico in the 1840s. What used to be pure cowboy, even in the 1950s, has turned pro.

Some things haven’t changed. Highest scores and fastest times still win, and, “You only get paid if you win,” bareback rider “Pistol” Pete Hawkins says. “You don’t have a $17 million contract and a Benz and a Bentley parked in the garage.”

Yet differences go beyond money.

“Back in the ’50s,” Tucson Rodeo General Manger Gary Williams says, “it was not uncommon to see guys compete in four-five events at both ends of the arena. You used to see guys who would ride bulls and bucking horses and steer wrestle, calf rope or team rope. But rodeo has become so competitive today, there’s only a handful of guys who can compete in more than one event, much less at both ends of the arena.”

Forget the little things (Team Tying becoming Team Roping, electronic timers replacing stopwatches). For cowboys, it’s a whole lot easier just entering rodeos with cell phones, a central entry system, PIN numbers and computers. “Before push-button phones,” says Larry Mahan, a six-time all-around champion in the 1960s and early 1970s, “you’d be there dialing your fingers off trying to get through to the rodeo secretary.”

Cowboys or athletes?

The biggest change, however, is the rodeo cowboy. “In my generation,” Mahan says, “most of us grew up with the cowboy way of life, and that’s why we got into rodeo. A lot, but not all of them, today are just really great athletes who could have gone into some other sport but picked the rodeo game.”

Case in point: bareback rider Jason Jeter. “I definitely wasn’t from a cowboy family,” Jeter says. “My dad was a businessman. Today, I would go out on a limb and say in the roughstock events, especially bull riding, that more than half of the top guys had nothing to do with ranching or cowboying growing up. They’re rodeo athletes and not rodeo cowboys.”

Today’s cowboys, er, athletes hire trainers. Instead of working cattle, they work out in the gym. And that massage therapy sign up in Denver reaches an audience.

“If I have something that hurts, I definitely do it,” Jeter says.

Hmmm. Can’t quite picture Casey Tibbs or Jim Shoulders getting a massage.

“Jim Shoulders scoffs at everything we do nowadays,” Jeter says with a laugh. “He would never use athletic tape if his life depended on it. We use it whether we’re hurt or not, just to keep from getting hurt.”

Valuable livestock

Livestock has improved, too. Stock contractors today have breeding programs, turning out top-flight roughstock practically guaranteed to buck. Purebred Brahma bulls have become a rarity on the circuit.

Legendary stock contractor Harry Vold got his start in 1948 when he camped out and night-herded about 100 head of stock to a local rodeo. “They were only worth about $4 a head,” he says. These days, he uses a huge crew and big rig transporters. Bucking stock is a lot more valuable—a top bull can fetch around $50,000—and, oh, yeah, Vold sleeps in hotels instead of under the stars. “Lot more comfortable,” he says.

Rodeo promotion

Bringing in spectators used to be challenging, as well. Gay laughs at some of his early promotional efforts.

“Newspapers were not very good about doing any stories on rodeos,” Gay says. “I don’t think anyone in the newspaper business knew anything about rodeo and weren’t interested in learning.”

For the 1958 season opener at Mesquite, Gay says a bull rider—“really a daredevil of all sorts”—volunteered to skydive into the arena. “I asked him, ‘Are you sure you can hit it?’” Gay recalls. “He said, ‘Shoot, yeah.’ Well, the wind kicked up a little that day, and he missed the arena and landed in the high-line wires about 100 yards away. He didn’t get hurt, and we did get a story in the newspaper.”

Medical/Crisis programs

Yet no one laughs at rodeo’s two greatest additions: medical and crisis programs.

Dr. J. Pat Evans and athletic trainer Don Andrews conceived a mobile sports medicine system in 1980, providing medical services at pro rodeos. Today, the Justin Sportsmedicine Team, with permanent facilities in Guthrie, Oklahoma, and Mesquite, Texas, attends more than 100 events and treats 6,000 cases a year.

In 1989, Justin Boot Co., the PRCA and Women’s Professional Rodeo Association created the Justin Cowboy Crisis Fund to provide financial assistance in the event of “catastrophic injuries” to competitors.

“In my day, you was on your own,” Shoulders says. “There were a few major rodeos that would have a first-aid thing, but as far as a crisis fund or anything like that to kinda help you out … well, it was like if you asked me what the retirement fund was when you quit rodeoin’, I’d say it was whatever you had in your ass pocket. The Justin Crisis fund has really been a lifesaver for a lot of guys.”

Hawkins knows that all too well.

After breaking his leg in 2004, Hawkins underwent three operations and left the hospital, 15 days later, with a plate and 16 screws in his leg. Total cost: $284,000.

“I don’t have $284,000,” says Hawkins, who spent four months in a wheelchair after leaving the hospital. “I had broken my back in 2000, but this was a different deal with a pregnant wife. Justin Cowboy Crisis came in and really helped us out, but it’s not just my story, and it’s not just the medical bills. They provide athletic tape, and I’d go through $600 worth of tape a year. That’s a lot of tape.”

Corporate sponsors

Which brings us to the role of corporate sponsorships.

“I never had a sponsor when I was rodeoing,” Gay says. “John Justin and I were pretty good friends, so I’d get a free pair of cowboy boots every now and then, but that was about the extent of it.”

Shoulders didn’t sign with Wrangler until 1958, and rodeo didn’t find a real commercial pitchman until Mahan—the first rodeo cowboy on a Sports Illustrated cover—broke the mold during his record career. Athletes sign more endorsement and sponsorship deals today. “You still have to pay your dues,” Hawkins notes—but the corporate money game isn’t new.

Wrangler has been a sponsor of the pro circuit since 1947, and in 2001 became the first company to have its name attached to the National Finals Rodeo.

NFR and PBR

There was no National Finals Rodeo until 1959. Rodeo’s super bowl before the NFR was held at, of all places, Madison Square Garden in … New York City?!?!

“It was a lot like the NFR nowadays as far as the money,” Shoulders recalls. “If you got hot at New York, you could make up an awful lot of slack from all year. ’Course, you had to beat a few more people, wasn’t limited like the Finals now to 15 guys.”

When the old Garden was torn down, the rodeo, suffering declining attendance, died with it. By then, however, there was the National Finals Rodeo.

The NFR moved from Dallas in 1962 to Los Angeles, then to Oklahoma City in 1965, and finally, in 1985, to Las Vegas, lured by a $1.79 million purse (up from $901,550).

On the other hand, in the 1950s, there was no such thing as Pro Bull Riders. The PBR was born in 1992 when 20 PRCA competitors decided to make bull riding a stand-alone sport. The first PBR tour, two years later, consisted of eight events for a combined $250,000. That has grown to 29 cities and $10 million. You’d think the two tours wouldn’t like each other, but that wouldn’t be the cowboy way.

“It’s a win-win situation for just about everybody,” Mahan says, and Gay agrees. “It’s creating a lot of new rodeo fans.”

And what about those bull riders today, wearing protective vests and helmets? Isn’t that un-cowboy? Mahan doesn’t think so. After all, they can prevent serious injuries. “But we weren’t smart enough to figure that out back then,” he says.

Where rodeo goes from here is anyone’s guess. Some look to increased TV exposure, which propelled NASCAR and the PGA Tour into mainstream America. In 1979, stock car racing left its Southern roots in the dust when CBS televised the Daytona 500 live for the first time.

Of course, having race leaders Donnie Allison and Cale Yarborough wreck on the last lap, allowing Richard Petty to win, followed by a go of fisticuffs between Yarborough and the Allison brothers (Donnie and Bobby) created a lasting image. Yet few believe rodeo can repeat NASCAR’s success story.

“This may have been lightning in a bottle,” says Jim Pedley, a sportswriter with the Kansas City Star. “Every niche sport in the world right now is trying to figure out what happened with NASCAR.”

Adds Williams: “I don’t think rodeo will ever totally be as mainstream as NASCAR. For one thing, everybody who drives a car can kind of fantasize on their morning commute to work about driving in the Daytona 500. But it’s kind of hard to fantasize about rodeo because we’re becoming more urban and less rural.”

Besides, no one’s really longing for Billy Etbauer and Cody Demoss to duke it out at the Calgary Stampede.

Certainly, rodeo will see more changes over the next 50 years. “I think it’s going to become more of an athletic sport rather than a cowboy sport,” Jeter predicts. “Eventually you’re not going to see many traditional rodeo cowboys rodeoing, because they’re not going to have time to do those traditional cowboy chores and still be competitive athletically.”

But the sport will always be grounded in its Western history. “Things change in 50 years,” says Melody Groves, author of the forthcoming Ropes, Reins, and Rawhide: Understanding Rodeo. “But the sport of rodeo, the cowboy code and way of life remain solid. As long as there are cowboys, there will be friendly sparring matches.”

Meanwhile, Jim Shoulders has no regrets that he isn’t competing today. “I never was one for tryin’ to live in the past,” he says. “That’s like the old story: wish in one hand and spit in the other and see which one gets the fullest. A lot of guys wish this and that, but it don’t do ’em much good. That’s why I quit rodeoin’. I couldn’t beat nobody and the ground got too hard.”

Yep, 50 years later, cowboy logic is still the same.

Johnny D. Boggs has been bucked off horses, gotten his boot caught in a stirrup, eaten dust, pulled leather, lost his hat and stepped in numerous cow pies—and he’s not even a rodeo .

Photo Gallery

A bareback rider (left) guards against hyperextension by taping his upper arm into a slightly bent position. Athletic tape is something that a 1950s’ cowboy would laugh at, but today’s cowboys say that they’re just smart enough to take care of themselves.

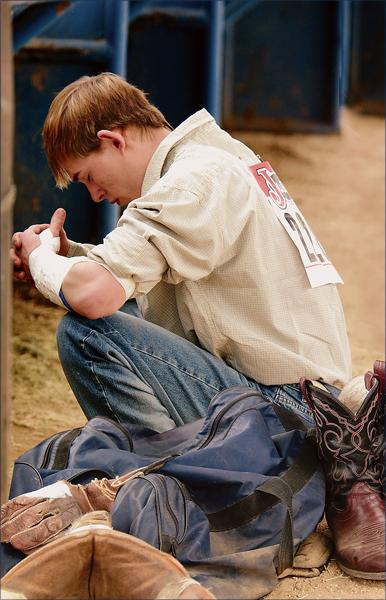

Will rodeo be simply another athletic sport when this young cowboy grows up? Or will today’s cowboys fight to preserve the sport’s Western history ties?

Although rodeo cowboys have changed since their 1950s’ counterparts, some still preserve the cowboy way of life, such as this cowboy (below), praying for guidance. He may be reciting a personal prayer, or he may be drawing on the words from the 1960s’ rodeo prayer written by Clem McSpadden and asking for help “to compete as honest as the horses [I[ ride and in a manner as clean and pure as the wind that blows across this great land of ours.”

– All photos by Bonnie Adams unless otherwise noted –

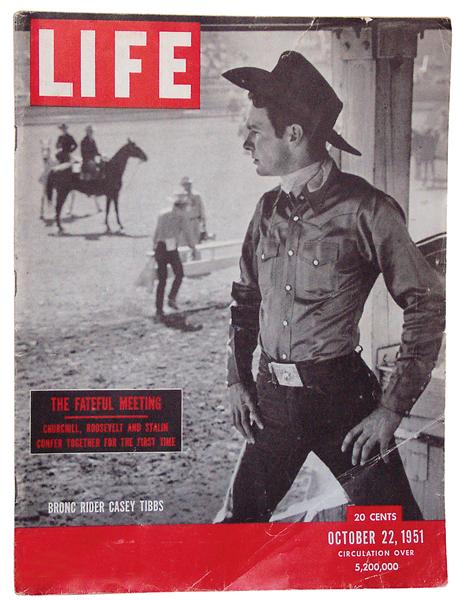

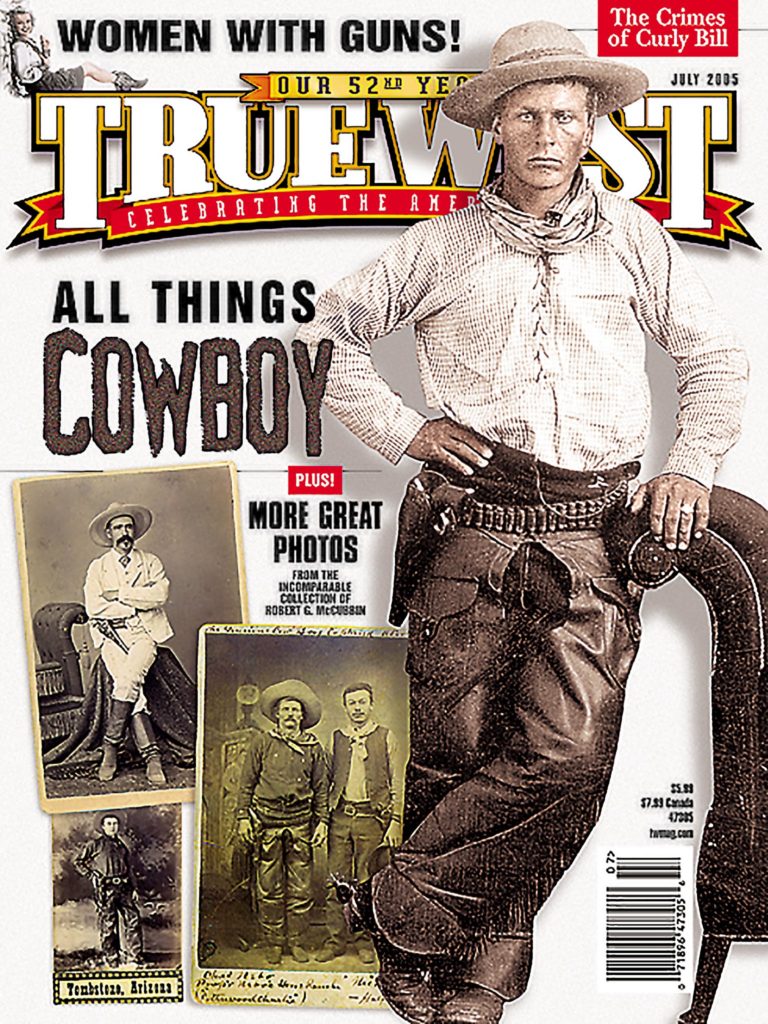

Casey Tibbs broke in his saddles by running them over with his purple Cadillac. Although that sounds like something today’s rodeo athlete would do, Tibbs did have the soul of a working cowboy, having grown up on a ranch in South Dakota. As the youngest man to win the national saddle bronc-riding championship in 1949, Tibbs was featured in Life magazine in its October 22, 1951, issue (right).

– True West Archives –