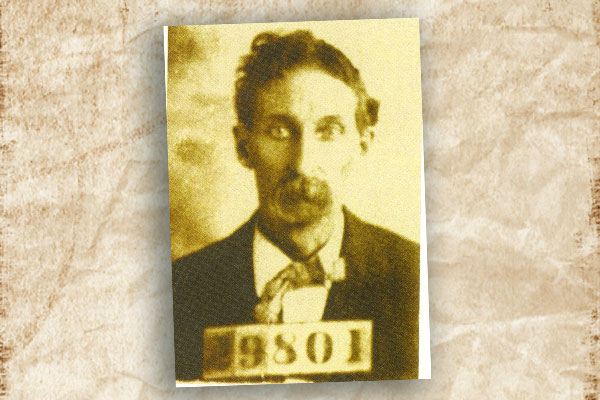

Outlaw John Shaw gulped his last whiskey while surrounded by 15 cowboys as the sun rose over the cemetery in Canyon Diablo, Arizona Territory. One problem: John Shaw was already dead.

Outlaw John Shaw gulped his last whiskey while surrounded by 15 cowboys as the sun rose over the cemetery in Canyon Diablo, Arizona Territory. One problem: John Shaw was already dead.

A dead guy having a pick-me-up should fall squarely into the category of legend, and an easily dismissed one at that. But the story of Shaw’s last drink is derived from photographs and eyewitness testimony. The episode exemplifies how the West was more than wild. Sometimes it was plain weird.

A Gunman’s Opera

When Shaw and William Smith (a.k.a. William Evans) entered Winslow’s Wigwam Saloon around 1:30 a.m. on April 8, 1905, they bellied to the bar and ordered drinks. But a stack of silver dollars on a nearby dice table proved more interesting. The two roughnecks drew pistols on the dice players and backed out the door with $271, never touching their drinks.

In their haste, the duo left a trail of coins near the railroad depot, leading lawmen to deduce that the thieves had walked the tracks before hopping a train. Navajo County Sheriff Chet Houck and Deputy Pete Pemberton tracked the outlaws to Canyon Diablo, 25 miles west of Winslow. They asked trading post operator Fred Volz if he’d seen the men. While Volz gave the officers a description of the men he’d seen, Smith and Shaw came into view, walking toward the depot.

Houck called, “I want to look you over.”

The impetuous Shaw spun around and yelled, “You can’t look me over!”

Shaw drew and fired from such close range, according to Flagstaff’s Coconino Sun, that the powder burned Houck’s hand. Luckily, the bullet passed through the sheriff’s coat.

What followed was a kind of gunman’s opera, mostly comedic, the players performing with jangled nerves under a cloud of hot smoke.

Four men, as few as four feet apart, blasted at one another for the time it took to fire 21 shots. One man died. None of the others were badly hurt.

Houck killed Shaw with his final shot. The robber had run out of ammunition, and while Shaw was turned sideways, Houck fired a bullet through his head.

Pemberton’s last shot hit Smith’s left shoulder as he zeroed in on Houck. The impact distorted Smith’s aim, and the bullet nicked the sheriff’s stomach, sparing his life.

In addition to the fatal shot, the Sun reported that Shaw was hit in three places, and so was Smith, though not seriously.

A bullet also grazed Pemberton, who had violated a cardinal rule of gunmanship by putting bullets in all six chambers of his weapon, increasing the risk of an accidental discharge. (The other participants carried five bullets.) But Pemberton’s boldness in loading that sixth round proved fateful. It decided the fight in favor of the lawmen and saved Houck’s life.

“Let’s Give Him a Drink”

Volz provided a pine box from his trading post for Shaw’s hastily-done burial, before the lawmen took Smith to the Winslow hospital. The next night, word of the shoot-out spread through the Wigwam Saloon, which was packed with cowboys from the Hashknife, a Northern Arizona cattle outfit.

Many of these cowboys had shady pasts that included rustling, and none liked the law. But what really got everyone hot was the idea that the robbers hadn’t touched their drinks. Getting shot was one thing; being deprived of your paid-for whiskey was outrageous.

Fifteen of the cowboys got so worked up that they grabbed their whiskey bottles and jumped aboard the next train to Canyon Diablo. When they arrived, they pounded on Volz’s door, waking him up.

Angry and aghast at their purpose, Volz eventually calmed down and loaned them shovels. He also gave the mob his Kodak square box-camera, saying Houck had wanted a photo in case of a reward.

“We stopped at the depot and had a few more drinks and then we went and dug the grave open with the shovels,” a cowboy named Lucien Creswell said.

Shaw had a friendly grin on his face, “looking very natural, his head not busted open” by the bullet, he added. “Some of the boys almost cried when they saw Shaw lying there so lifelike,” but stiff as a board.

J.D. Rogers, the Hashknife’s wagon boss, told the men, “Let’s get him out. Let’s give him a drink and put him away proper. Somebody can say a prayer, which wasn’t done when they shoved him into that hole.”

Two men dropped into the grave and “lifted the body upward into reaching hands,” wrote Gladwell Richardson in Arizona Highways in 1963.

“They stood it up against the wood-picketed grave of another luckless man … and gave him a drink from a long-necked bottle, pouring the whiskey between the tight teeth, the death-fixed grin of a man who in life must’ve been easy going, happy-go-lucky,” Richardson wrote.

As dawn broke, the cowboys jerked off their hats and mumbled a prayer. Into the casket they placed the bottle from which Shaw had drunk; then they returned the dead man to his rest.

Prison Mates

The story of John Shaw’s last drink also has a weird postscript.

Eight months after the gunfight, a drunken Pemberton, angry over gambling losses in Winslow’s Parlor Saloon, shot town marshal Joe Giles five times, killing him. Pemberton was convicted of second-degree murder and sent to Yuma Prison, where William Smith was serving his sentence for the Wigwam robbery.

History doesn’t record what prison yard chats the two must’ve had about their gunfight and its weird aftermath in the Canyon Diablo Cemetery.

Tucson-based Leo W. Banks is a frequent contributor to Arizona Highways and The Los Angeles Times. He has written three books about the Wild West in Arizona, including Double Cross, published in 2001 by Arizona Highways Books.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy Arizona Historical Society; John Shaw Collection –