Female journalists were a novelty in the late 1800s.

Female journalists were a novelty in the late 1800s.

The noisy, smoky newsroom was hardly the place for a gentle sex whose “sphere” was the home and who had decades to go before getting the right to vote. Then came Nellie Bly and boy, did things change!

The name rings a bell with many but only in a vague way. Nellie made her name as an undercover reporter—“stunt reporting,” they called it. Her most famous moment came in 1889-90, when the 25 year old traveled around the world in 72 days, beating the fictional account of Jules Verne’s hero, Phileas Fogg, in the book that then was a worldwide best seller: Around the World in 80 Days. The book had been published in 1872, two years after George Francis Train set the 80-day record when he circumnavigated the globe. (He also beat Nellie’s record a few months after her trip when he made it in 67 days.)

But her stunt reporting is not why Nellie—born Elizabeth Cochrane on May 5, 1864—is celebrated as a woman of the West. She comes by that because of one of the most forgotten parts of her resume: In 1885, Nellie spent six months traveling throughout Old Mexico to tell her readers what America’s neighbor was like. Her report wasn’t just the usual travelogue of sights and sounds; it was also a biting indictment of the poverty she found and the corruption apparent in the presidency of Porfirio Diaz. The resulting articles so infuriated Mexico City that Nellie was banned from the country.

Her editors tried hard to talk her out of the trip, but she was determined to go and do “something that no other girl had ever done,” reports her biographer, Brooke Kroeger, in her excellent 1994 book, Nellie Bly: Daredevil, Reporter, Feminist.

When you look back at her life, it’s obvious Nellie did lots of things girls had never done before. Even though some in journalism have downplayed her contribution to the field—dismissing her as a gimmick—that’s not the way she’s seen by the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. It calls her a “trail-blazing journalist considered to be the ‘best reporter in America’ who pioneered investigative journalism.”

An Outraged Teenager

Elizabeth Cochrane could hardly believe the narrow-minded tripe in Pennsylvania’s Pittsburg Dispatch column, declaring “What girls are good for” was only housework and caring for children. She was 18 years old and had been helping support her family since her rich father had died without a will, thereby denying his home and possessions to his wife and 15 children.

Elizabeth was well aware how hard “working girls” like herself had it, and she wrote an impassioned letter to the editor. He was so impressed, he hired her. For her “pen name,” the editor chose a song made popular by Pittsburgh’s own Stephen Foster (although he changed the spelling of Foster’s Nelly Bly).

Among her first assignments, Nellie explored the plight of Pittsburgh’s poor working girls, shared the need to reform divorce laws (her mother had a disastrous second marriage that ended in divorce) and investigated child labor (there were yet no child labor laws in America). Her reporting was “full of fire,” the U.S. National Archives notes. But the editor pulled back when advertisers complained about her exposes, and Nellie was put to work in the “normal sphere” of female reporters, covering cultural and social events.

Nellie would say she was “too impatient to work along at the usual duties assigned women on newspapers,” and decided to make a new mark. “By distinguishing herself at foreign reporting, she reasoned, she could explode the ossified mind-set of editors who had relegated her for no good reason to work she considered dull, meaningless, and without the potential for promotion,” Kroeger notes.

The World’s Worst Monarchy

Nellie set off with a rail pass for six months in Mexico, accompanied by her mother as chaperone.

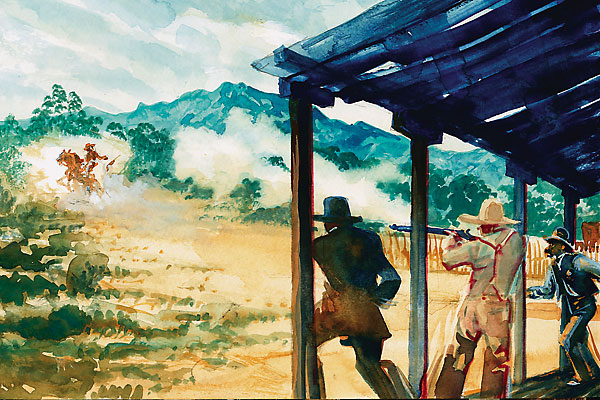

Her stories were blunt and honest—she told it as she saw it, even as she saved her harshest criticism for the government until she’d returned to the states, knowing if she revealed her contempt of the country’s policies while still traveling, she would be arrested or expelled. The prospect of jail clearly terrified her: “A Mexican jail is the least desirable abode on the face of the earth, so some care was exercised in the selection of topics while we were inside their gates.”

“Bly sought to write about subjects that would cut against the prevailing stereotypes of the country and its people,” Kroeger notes. “For example, she advised the women of Pittsburgh … to hire Mexicans as servants because they would find them clean (except in the preparation of food, which could be taught), industrious, honest, and uncommonly hardworking, if a bit slow.”

Nellie wrote about expatriates and Mexico’s ruling class; she applauded a proposal by the governor of Chiapas to end illiteracy of Indian children throughout Mexico. She wrote about Mexican customs and protested the incarceration of a Mexican journalist who had criticized the government.

When copies of her articles made their way back to Mexico City, officials were less than happy, and Bly cut short her visit because she feared being arrested. Once home, she unleashed her harshest criticism. She described the Mexican press as “tools of the organized ring” and decried the government as “the worst monarchy in existence.” By the time she was done, government officials made it clear they never wanted Nellie Bly within their borders again.

Joseph Pulitzer hired her in 1887 for his New York World, where she reprieved and honed her early approach to investigative journalism. She spent 10 days in the insane asylum on Blackwell’s Island (present-day Roosevelt Island), discovering patients who were fed vermin-infested food and were physically abused, and some sane patients who had been institutionalized by malicious families. Her stories led to much-needed reforms at the asylum. She also posed as a criminal and lived inside a woman’s prison, again revealing deplorable conditions that were cleaned up after her expose.

She used this undercover approach again and again, and was quickly copied by competing newspapers that sent out their own female reporters. None of the others ever matched her popularity, nor her style. Nellie’s career would span 36 years and included some 600 first-person stories.

Nellie Bly was a name known throughout America. “Bly’s ‘push-and-get-there’ style helped to change the way reporters did their jobs. Bly also was a shining example of why women deserved the same opportunities as men,” reports Sean McCollum in a Scholastic article, “Daredevil Reporter.”

An “American Experience” PBS program on Nellie (see sidebar) noted “the young reporter always sided with the poor and disenfranchised.” Her fame also opened doors, and the “get” interviews of the day were gotten by Nellie Bly: Boxer John L. Sullivan, suffragist Susan B. Anthony, anarchist Emma Goldman.

These days, she is mostly remembered for a stunt that gave her worldwide attention.

In 1889, she set out to beat the “80 days around the world” of Jules Verne’s famous novel, which then was in its fourth printing. Joseph Pulitzer thought up the stunt as a circulation booster and intended to send a man. Nellie threatened to offer her services to another paper—promising to beat Pulitzer’s man—if he didn’t send her. He did, and she left on November 14, 1889, carrying a single satchel and wearing her one traveling outfit and a checkered coat.

Nellie beat the record, returning to New York in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes and 14 seconds. The trip, chronicled daily on the front page of The New York World, did wonders for circulation.

Parades were held in Nellie’s honor, but back in the newsroom, things had turned sour. While she’d obviously expected a generous bonus for the new riches her stunt had brought the paper (and mindful that her salary wasn’t generous in the first place), she was horribly disappointed that she got not a cent. She quit and left journalism for a few years but eventually returned.

In 1895, she married Robert Seaman, a millionaire many years her senior, who owned a steel barrel company. He died in 1904, and she took over his company, putting her money where her pen had been, providing health care and libraries for her workers.

She was in Europe at the outbreak of WWI and became the first female reporter on the front lines, while reporting for the New York Evening Journal.

Elizabeth “Nellie Bly” Cochran Seaman died of pneumonia on January 27, 1922. Her obituary in The New York World stated, “Nellie Bly was THE BEST REPORTER IN AMERICA and that is saying a great deal.”

The last word, fittingly, should belong to Nellie Bly. Here is her formula for success: “Determine Right. Decide Fast. Apply Energy. Act with Conviction. Fight to the Finish. Accept the Consequences. Move On.”