“I felt like crying, for the sacred hoop was broken and scattered.

“I felt like crying, for the sacred hoop was broken and scattered.

The life of the people was in the hoop, and what are many little lives if the life of those lives be gone?”

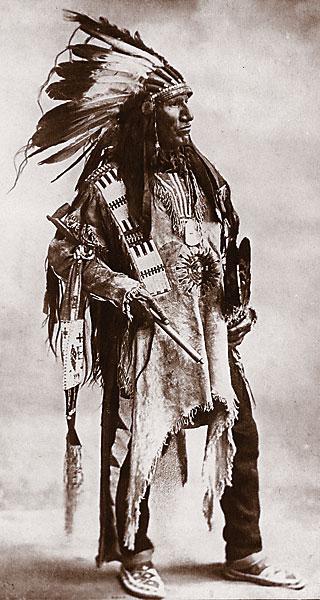

Those were not Chief Black Bird’s words, but they may very well have been. They were expressed by Black Elk, a fellow Lakota who would also grab at his chance to improve the lives of the people by accepting Buffalo Bill’s 1886 offer to appear in a Wild West show. Black Bird would himself appear in an overseas show under the famous showman, in 1903, but first, he struck out with Fred T. Cummins’s Indian Congress. Photographs document his presence at the Indian Congress for the 1899 exposition in Omaha, Nebraska.

By then, Black Bird had likely realized his way of life was over. His name appears in the Crazy Horse Surrender ledger in May 1877, indicating he had participated in the Great Sioux War. Around 1880, he was listed on the Red Cloud Agency census at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, as #240 Black Bird. In November of that year, his “X” was marked along those of other leading Oglala Sioux, including Chief Red Cloud’s, to grant permission for railroad passage through the sacred Black Hills. And his people had cast their dying gasp to regain their culture at Wounded Knee in December 1890. In the 1890s, faced with a monthly wage of $10 on the reservation, versus the $25 starting pay (sometimes going as high as $125) Black Bird could make with a Wild West show, his decision to leave likely made the best sense to him. Instead of breaking his back digging ditches, he’d perform on horseback.

Show Indians, known as oskate wicasas, also made money posing for photographers, which Black Bird and his daughter, Womboli, did while they toured with Cummins’s Indian Congress at Coney Island in 1903. They sat for the sake of Adolph A. Weinman, a sculptor who had been commissioned to create an Indian statue for the 1904 exposition in St. Louis. Weinman excitedly reported: “I had long been wanting to do some Indian subjects…. I went into this work with boundless enthusiasm and utter disregard of cost. I looked up all possible sources of information on the manners, customs and costumes of the various tribes of the North American Indian.” With his “utter disregard of cost,” he may very literally have bought the shirt off of Black Bird’s back.

That’s my theory, at least, because Black Bird’s shirt ends up in the collection of two Westport, Connecticut, residents: etiquette maven Amy Vanderbilt, who sold it in 1960 to Western artist Ed Vebell; he sold it in 2007. I have a strong suspicion that it ended up in Westport through this direct connection Weinman had with Black Bird.

You see, Weinman had a close friend in another Westport resident, James Earle Fraser. Both sculptors studied together at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Their love of metallic arts stemmed from their shared mentor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens; Fraser would end up designing the 1913 buffalo nickel, while Weinman created the mercury dime and walking liberty half-dollar in 1916. Three years later, Fraser was the first recipient of the J. Sanford Saltus Award, given in recognition of metal artisan achievement, an award Weinman designed (he earned the medal the following year). They also worked together on statuary commissions for building projects such as the Missouri State Capitol and the National Archives Building.

Yet Fraser was truly the more connected of the two when it came to Lakota culture. From his 1876 birth year, he had followed his rail engineer father around the West. His years in the Dakota Territory were actually what got Fraser in Paris in the first place. His family had moved to Chicago in 1890, the same year that the Lakota suffered a death blow at Wounded Knee. Fraser apprenticed under sculptor Richard Bock, who was preparing for the city’s 1893 exposition. When Fraser walked around that show, he saw works such as Cyrus E. Dallin’s Chief at Sunrise, showing Indians in their glory. Growing up with the Sioux, he understood the depths to which they had fallen. The 17 year old cast a model of End of Trail in 1894, which got him a ticket to Paris; in 1915, he won the gold at the San Francisco exposition for the finished sculpture that showed a slouching Plains Indian on his equally crestfallen horse.

In his later years, while living at the Westport home he had purchased in 1913 with the proceeds from his buffalo nickel, Fraser recalled sleeping under buffalo robes as a boy: “On one the sun was painted with its rays extending to the edges; on another the moon and stars, all in beautiful and appropriate colors and fine design. I have looked through museums in vain to find the equal of those paintings.”

Perhaps hearing Fraser express a similar sentiment to him, Weinman gave his friend a piece of his homeland he had been seeking since he was a boy.

The Chief Black Bird ceremonial shirt set a new record for the highest auction price paid for Indian Art. On May 18, 2011, the hammer went down at Sotheby’s New York for more than $2.5 million, beating out the previous record of $1.9 million for a Tlingit war helmet that sold at Fairfield Auction in Newton, Connecticut.

Photo Gallery

This photograph of Chief Black Bird was captured by Heyn & Matzen Studio during the 1899 exposition in Omaha, Nebraska. Fred T. Cummins shared another Heyn photo, of Black Bird in this same garb, appearing with nine other Lakotas, in a promotion for his Indian Congress at the 1901 exposition in Buffalo, New York.

– All images courtesy Sotheby’s New York –