The little mining camp that could and did survive is none other than Deadwood, South Dakota, the best character found on HBO’s Deadwood series, which premiered on March 21 with 5.8 million viewers—the best yet for an original HBO series debut, according to Variety.

The little mining camp that could and did survive is none other than Deadwood, South Dakota, the best character found on HBO’s Deadwood series, which premiered on March 21 with 5.8 million viewers—the best yet for an original HBO series debut, according to Variety.

And it took only two episodes to air before HBO ordered a second season. “This is TV you lean forward for, and we have been pleased with it on all fronts,” says Carolyn Strauss, HBO’s entertainment president.

The historical Deadwood evolves from a mining camp into a “little city that had a life, and a spirit, and a soul of its own,” as Watson Parker wrote in Deadwood: The Golden Years. After almost two months of Deadwood’s grimy TV double, with its unkempt, uncouth “citizens,” series creator David Milch can only hope people agree with Parker’s belief that Deadwood’s “personality is worth recording before the colors fade.”

Even a place littered with dead pine trees can succeed. And it’s all due to those rough and tumble characters that bump their way along the trail and stay. Some won’t survive the lawless mire, but some will. And how and why they do is the heartbeat of the series.

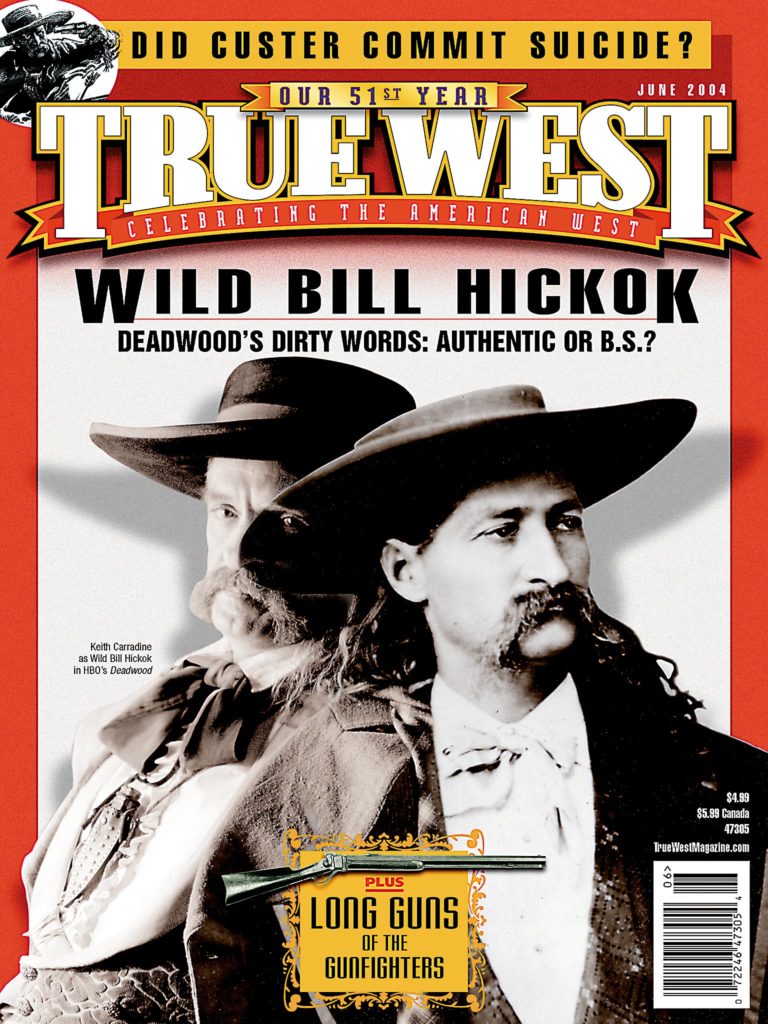

An example of this stems from the series’ most notorious character—Wild Bill Hickok (played by Keith Carradine). His traveling companion, Charlie Utter (Dayton Callie), can’t save him from the drinking and gambling that keeps Hickok from staking his claim and ensuring a better life for himself and his new wife. In episode four, Hickok dies at the poker table in the #10 Saloon, shot by fellow gambler Jack McCall (Garret Dillahunt).

And the person who is most like this former Kansas sheriff (Hickok) is another sheriff, who Hickok affectionately nicknames Montana, as that is where Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant) wore his badge. But Bullock has traveled to Deadwood to establish a hardware store with Sol Star (John Hawkes), who keeps his partner out of trouble—that is where Utter fails his friend Hickok.

There’s even a poignant scene in a gross backdrop in which Utter, while urinating in the street, calls out to the two merchants, asking them how Bullock and Hickok can share the same personality, but not the same success. Talking about his character, Hawkes says that “in a private moment, Sol confides to Charlie that he’s not sure Seth has the patience and subtle people skills for business. I might have told him that it’s a battle keeping partners like ours under control—that it requires vigilance and a keen instinct knowing when to push them and when to let them be.”

Star not only hands over a “peace” commode to keep Bullock and a man in the street from fighting when the duo first enter town, but he also handles tougher business dealings with “a light-hearted nonchalance,” as Hawkes says about him. Star negotiates the land payment for their hardware store with Al Swearengen (played by Ian McShane), the Gem Theater proprietor, who doesn’t take kindly to those threatening his business (he has Mr. Wu feed their bodies to his pigs) and is suspicious of the Montana lawman and his aims in Deadwood—as would be anyone whose livelihood depends on others gambling, drinking and buying ladies of the night.

Ultimately, Deadwood’s survival lies in the hands of these two men. Swearengen helped build the town, and although the citizens don’t trust him, they do enjoy the way he lies. And Bullock will be elected the town’s first sheriff because of Hickok’s death. (The Deadwood townsfolk don’t welcome law and order entirely because they find Hickok’s killer, McCall, innocent of his crime.) The everyday question on Main Street is sure to be: Will Swearengen or Bullock win today?

Well, maybe not. It’s missing a curse word or two.

“Lawlessness of the language”

“Whiskey” may be the first word Hickok says when he reaches Deadwood, but it isn’t the first thing out of his mouth. Why Hickok knows how tight a bull’s “butt” is during fly season is something he doesn’t reveal. Not that anyone would dare to ask him.

Nothing epitomizes Deadwood’s rough nature as much as the characters’ profanity, ranging from Hickok’s purple prose to endless streams of the F-word. The first time Calamity Jane (played by Robin Weigert) steps on the scene, she makes sure everyone knows how she feels about the people whose wagon is stuck (and ignorant is the least insult she uses). But series creator Milch hopes the audience will get used to “the lawlessness of the language,” adding that “it establishes an atmosphere, verbally, in which anything is possible. It is the rejection of everything, except brute force.”

And “brute force” was certainly a tactic the country was long familiar with in its quest for Manifest Destiny. In 1876, the United States was celebrating its centennial, even in towns such as Deadwood in the Dakota Territory, where thousands had flocked to the Black Hills, searching for gold. The rivers hadn’t stopped flowing, but that didn’t stop the prospectors from disobeying that covenant of the Laramie Treaty of 1873 and trampling the Sioux’s right to the territory.

Yet, Deadwood was home to more than just placer miners, as the series shows, and it is the varied cast of characters, whether they’re real or fictional, that Milch hopes will educate the show’s audience about the mores and ethos of a society.

Character Gold Dust

Most cast members credit Milch as their character guide, but Carradine best sums up why. When Milch related anecdotes about the setting and time and speech, he imparted “pounds of ‘character gold dust.’”

By episode four, Milch knew the characters so well that he told Weigert he was just “chasing them with a pencil.”

One of Deadwood’s cleanest citizens is Alma Garret (Molly Parker), who leaves New York with her husband Brom (Tim Omundson) so he can strike it rich in Deadwood. She married not for love, but out of duty to her father, who suffered from the financial panic of 1873 and was in dire need of money. Alma copes with her fate by taking daily doses of laudanum. When Brom’s dead body is carried back to town after a day at his claim, Alma is given the opportunity “to forge an identity for herself outside of the boundaries that have been assigned to her by the society that she comes from,” says Parker.

Alma, like many of Deadwood’s new arrivals, stays in E.B. Farnum’s Grand Central Hotel. Farnum (William Sanderson) spies and snitches on Deadwood affairs to Swearengen. When Cy Tolliver (Powers Boothe) wants to establish a rival establishment in town, he first asks Farnum if his hotel is for sale. It isn’t, but Farnum tells him of another man who is willing to sell. When Tolliver and partner Joanie Stubbs (Kim Dickens) open the Bella Union, Swearengen is roaring to know who alerted the com-petition, making Farnum’s palms sweat even more than usual.

Other people connected to Swearengen include Trixie (Paula Malcomson), his best girl at the Gem, Johnny Burns (Sean Bridgers), eager to learn Swearengen’s tricks of the trade and Dan Dority (W. Earl Brown), who does his dirty work, including killing Brom. (The claim was first sold to Brom because it was deemed worthless, but then it was discovered to pay out.)

Tom Nuttall (Leon Rippy) owns the #10 Saloon; Rev. H.W. Smith (Ray McKinnon) ensures that even the worst people get proper burials; A.W. Merrick (Jeffrey Jones) edits and reports for The Deadwood Pioneer; and Doc Cochran (Brad Dourif) does what he can to preserve life in the grimy town (whether it’s taking care of prostitutes at the Gem and Bella Union or saving the life of a young girl whose family was massacred for money).

My secret love became impatient to be free

If any character keeps you wondering, it’s Calamity Jane—no mascara and no musical numbers for this girl (sorry, Doris Day fans). She may swear up a storm, but her gratuitous nature and compassion lighten up even her darkest scenes.

The only secret love that is impatient to be free is not Jane’s love of Hickok, but her love of her fellow man. And for this portrayal of her, we are most grateful to Milch. If nothing comes out of the series but a fresh understanding of the West’s most “manly woman,” the venture will be well worth its run.

It can’t be easy to get in the mindset of a foul-mouth woman who sways and staggers while attempting to stay on equal par with the men. It takes talent to switch gears, as the real Jane often did, and reveal her gentle side, the part that cradles the rescued girl to sleep while singing “Row, row, row your boat gently down the stream.”

With the help of Jane Alexander, who played Calamity Jane in the 1982 TV movie Calamity Jane, and a few rodeo cowboys, Weigert nailed down her character to a T. The cowboys were her best resource. “Jane’s wide gait I got off them,” says Weigert. “And the way Jane speaks was partly informed by the cowboys’ surprising blend of bravado and shyness.”

Her coworkers even lent a hand in interpreting her character’s complex mind. Weigert admits that there is one scene that was particularly hard for her to get a handle on, crediting Malcomson and Dourif for saving her. “They’d been watching me struggling to follow a complex direction that I just wasn’t able to integrate. Brad told me during lunch break an observation of Paula’s, ‘She just wants to get the hell out of there and have a drink,’ and bang, everything fell into place.”

And what does the man who plays the most important person in her life have to say about her performance?

“I think Robin’s Calamity Jane is simply definitive,” says Carradine. “I believe the relationship [between her and Hickok] in the series is the closest to being a historically accurate depiction of that friendship so far. Everything I’ve read on the subject indicates there was never a physical relationship between the two—that Hickok took Jane under his wing as he was impressed by her spirit, and that she adored him as far as he would allow. That’s what we’ve shown in Deadwood.”

Not your father’s Western

By now, it’s pretty clear that Deadwood is not your father’s Western. There are no Black Hat/White Hat distinctions. No euphemisms cover up the way people really talked back then. No sunsets color the horizon.

As Carradine says, “My father was in several of the greatest Westerns ever made and they have stood the test of time.

Yet times have changed and society’s tastes have become more tolerant and in some areas perhaps more sophisticated. Deadwood is presented in a context where the way of life

in that place and time, complete with people’s habits of speech as well as proclivity for violence, can be shown

with more historical accuracy than was acceptable or permissible before.”

And that means Mr. Wu will keep feeding people to his pigs. We may hear the F-word as much as 50 times per episode. Soiled doves will kick up their legs (only to shoot their customers later in self-defense). And the fight for law and order will bring out the best and worst in people, just as it always has.

But it is the city itself—“a place of incredible danger and incredible possibility,” as Weigert describes Deadwood—that remains a catalyst for all the adventures and misadventures.

“To watch an utterly lawless place develop its own weird morality is fascinating and enlightening from the perspective of human nature,” says Carradine, who credits Milch’s fresh perspective for bringing the Western genre to a new level cinematically.

The world Milch depicts is so interesting, Weigert says, because even when cruelty has the upper hand, the radical freedom experienced by Deadwood’s citizens acts as an “active agent of good.” Without the protection of laws, the “people have to work together, if for no other reason, initially, than to buttress themselves against a world of potential enemies, and when they do … love is given a chance to enter and do its softening work on even the most hardened hearts.”