In 1962, no one was cooler or hipper than Frank Sinatra. The “Chairman of the Board,” later known as “Ol’ Blue Eyes,” headed a merry-making clan of top entertainers that included Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop. They were known as the Rat Pack.

In 1962, no one was cooler or hipper than Frank Sinatra. The “Chairman of the Board,” later known as “Ol’ Blue Eyes,” headed a merry-making clan of top entertainers that included Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop. They were known as the Rat Pack.

Las Vegas, Nevada, may have been a favorite hangout of these gents, but the world was their oyster. The Rat Pack had starred in the caper film Ocean’s 11 in 1960, and the casino heist movie had been not only a major hit, but also an out-and-out gas for the Rat Pack to make on the stars’ adopted home turf of Las Vegas.

So in late 1960, Sinatra began to spread the word around Hollywood that the Rat Pack wanted to remake Gunga Din, one of the most beloved adventure films in movie history, as a Western. Despite its out-of-favor, 1890s British colonial theme, Gunga Din, first released nearly 75 years ago, in 1939, remains a favorite of major filmmakers who include Steven Spielberg. It’s a grand film full of epic battles, brawling, but lovable sergeants and fanatical natives, all expertly directed by George Stevens, of Shane fame.

United Artists couldn’t wait to finance Sinatra’s film, but instead of Victorian British sergeants fighting their way through 1890s India, the Rat Pack transplanted the action to the American West of the 1870s, becoming sergeants in the U.S. Cavalry. Instead of fighting “Thuggee” fanatics, Sinatra’s troopers would battle it out with Ghost Dancing Sioux warriors.

Given our now more enlightened historical sensibilities about the Ghost Dance tragedy at Wounded Knee, such a storyline today would be considered incredibly outrageous. But the early 1960s were a different time—women were dames and broads, and American Indians were Indians, with no insult meant or taken. Sinatra and friends were actually big supporters of the growing Civil Rights movement.

Sergeants 3 would be one of only two films (Ocean’s 11 being the other) to star all five members of the Rat Pack. For this big Western budgeted at $4 million, in 1962, many of the clan’s extended Las Vegas gang made the trek out to the distant Utah locations for a few days to play cavalry and Indians.

Veteran screenwriter W.R. Burnett literally lifted whole scenes and dialogue out of the original RKO Gunga Din script, with only the names changed to “protect” the guilty. Burnett was an old hand who had written classic gangster movies, like the original Scarface in 1932 and the novel Saint Johnson that the first major Wyatt Earp movie, Law & Order, was based on. Sinatra would play Victor McGlaglen’s role from the original film, while Dean Martin got to ham it up in the goofy, but engaging Cary Grant role with Lawford as the U.S. Cavalry version of a suave Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Sammy Davis Jr. became the Western version of Sam Jaffe’s Gunga Din, the ex-slave Jonah Williams, whose only wish in life was to wear the blue coat of a U.S. cavalry trooper. Bishop created a new role as the regiment’s deadpan sergeant major.

Early press reports stated Sinatra had purchased the rights to Gunga Din, but as legal questions began to surface, Ol’ Blue Eyes’s lawyers backpedaled, claiming that Rudyard Kipling’s classic Victorian poem was in the public domain. At first, the Sinatra version was called Badlands. Then it was retitled Soldiers Three, to cash in on the Kipling connection. Kipling had published an anthology of British colonial Army stories under that name that had actually been made into a film by MGM in 1951. But Pandro S. Berman, Gunga Din’s original producer, was now on the payroll at MGM, which was making noise about its own remake of the 1939 classic.

Kipling’s famous tribute to the unsung “better man than I am” water boys who accompanied British troops on campaign had little to do with the original film’s storyline except for the water bearer character named Gunga Din and his relationship with a British soldier.

Outside of the geographical and cultural changes between Sergeants 3 and Gunga Din, everyone involved in Sergeants 3 had to have known how close the screenwriters were following Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s script. The filmmakers may have thought they were in the clear, since Gunga Din’s original studio, RKO, was defunct, but Kipling’s estate was not. After Sergeants 3 previews began airing in London, the estate’s lawyers brought suit, winning, according to The Hollywood Reporter, an out-of-court settlement of $10,000. Yet RKO’s script, not Kipling’s classic poem, had really been infringed upon in the remake.

By the summer of 1961, the Rat Pack headed out to Utah’s “Little Hollywood,” the beautiful area around Kanab and Bryce Canyon, to make the film. Sinatra assembled a pedigreed Western film crew, including executive producer Howard Koch, who had been making tightly budgeted cavalry and Indian Westerns in the Kanab area for almost 10 years. John Sturges signed on as director, having numerous big budget Westerns under his belt, including The Magnificent 7 filmed only two years before.

Two John Ford film veterans also joined in to loan additional Western veracity to Sergeants 3. Cinematographer Winton Hoch had won an Oscar for his Technicolor camera work on perhaps the greatest cavalry movie ever made, Ford’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, released in 1949. Art director Frank Hotaling had started with Ford on another Ford cavalry film, Rio Grande, in 1950. He also worked on Ford’s 1956 classic The Searchers, as well as the 1959 Civil War cavalry epic The Horse Soldiers.

During part of the film’s production, Sinatra and Martin were still performing their act back at the Sands Hotel in Vegas. Come Monday morning, a helicopter would swoop down, land on the Kanab High School football field and deposit a hungover Sinatra and Martin for transport to the day’s location. Without any fanfare, Sinatra insisted on repaying the high school, spending $50,000 to supply it with everything from new football uniforms to tractor mowers to groom the field.

Kanab was a little Mormon cowtown with only one hotel, and the social gathering point was the Dairy Queen. For a bunch of Eastern types, this place was the height of dullsville. Bishop quipped that, “My advice to everybody was to get two scoops, because after that there wasn’t a goddamn thing to do.”

Sinatra paid to have the local motel, Parry’s Lodge, reconstruct the top floor into a party suite where, most nights, the Rat Pack drank, played poker, flirted with Vegas party girls and watched constant viewings of Laurel and Hardy movies. Davis Jr. endeared himself to the locals by bringing in home movies of his act and hosting open showings at the high school auditorium, complete with ice cream and popcorn.

Sergeants 3 surprisingly came in on schedule, and on budget. The prop and weapons departments had a field day with all the on-set pyrotechnics, bringing in almost 900 Winchester rifles and carbines, 350 Colt revolvers, two caissons and cannon, 235 sabers, 35,000 arrows and 55,000 blanks.

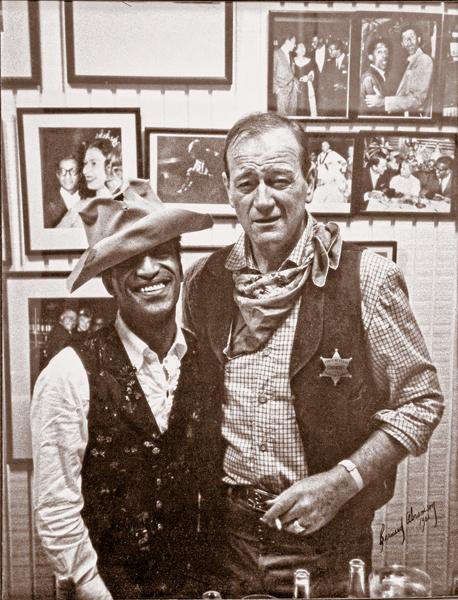

Davis was having a ball, more than anyone else. He absolutely loved the Old West and Westerns. Whether he was needed or not, he came out on the set everyday. Singer Mel Tormé, another entertainment industry Old West buff, had introduced him to quick draw and gun twirling with a single-action .45 Colt revolver. Davis developed into one of the fastest quick draw men in Hollywood, even using it as part of his nightclub act.

Rodd Redwing, a well-known American Indian movie gun coach, worked on Sergeants 3, and he traded pointers with Davis. The actor’s character had one major departure from Jaffe’s Gunga Din—Sergeants 3’s bugler survives the final battle and becomes a trooper in the all-black 10th U.S. Cavalry, the Buffalo Soldiers.

Davis also scored the best good luck charm any Western could ever have; John Wayne generously loaned Davis his wonderfully weathered, iconic cavalry hat that he had worn in all of the Ford cavalry films and in Rio Bravo. Even with extra padding in the liner, the hat still fit Davis loose, which added to the hand-me-down character of ex-slave Williams. But every time Sinatra or Martin walked by Davis, they jerked the hat down over his eyes and joked, “John Wayne, huh?” By the time Wayne got the hat back, the top front of the crown was badly torn, and the hat was ready to be retired.

Though in his 40s when he made this movie, Sinatra opted to perform a dangerous stunt involving a speeding buckboard, as he was chased by mounted Sioux warriors. Stunt coordinator Al Wyatt Sr. worked with the star. As that wagon sped along at 45 mph, Ol’ Blue Eyes was clearly hanging off of the side, in harm’s way.

Sinatra said of the romp-like films that the Rat Pack made, “Of course they’re not great movies…but every movie I’ve ever made through my own company has made money.” If the critics called Sergeants 3 a “$4,000,000 home movie,” that’s what the audience showed up to see—Sinatra and gang mugging it up for their own amusement, which made audiences feel like they were in on the joke. Viewers experienced other payoffs, like the incredible Utah scenery and a spectacular cavalry-versus-Indian battle with hundreds of mounted extras, dozens of Hollywood stuntmen and a classic cavalry-to-the-rescue ending.

Sergeants 3 spent three weeks as number one at the box office in 1962, but after several network TV showings, the movie disappeared for mass audiences—until five years ago. In 2008, a beautifully remastered DVD was finally released of this formerly “lost film.” Sinatra had it right—the movie may not have been a great film, but like the Bob Hope, Dorothy Lamour and Bing Crosby’s “Road” pictures, the Rat Pack’s Sergeants 3 is an entertaining throwback to a more freewheeling and innocent time.

Dan Gagliasso is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, screenwriter, magazine writer and historian who oncerode bulls on the amateur rodeo circuit.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Heritage Auctions –

– Courtesy Dan Gagliasso Collection/United Artists –

– Courtesy Dan Gagliasso Collection –