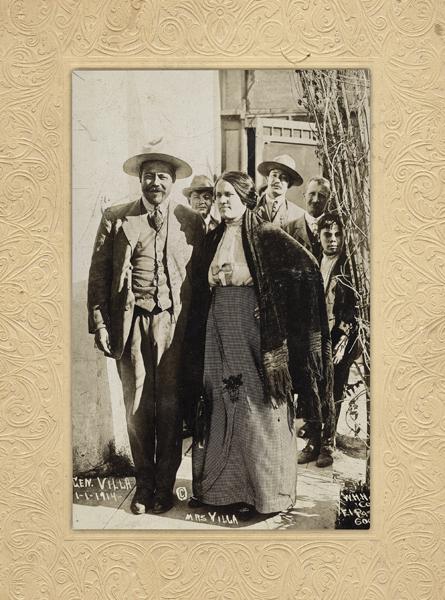

Doña L uz wasn’t the only woman in his life, nor even the only woman who claimed to be his wife. But the striking blue-eyed peasant woman was the first wife to the Mexican Revolution general, making her certificate of marriage the most valid, out of all the women Pancho Villa later married.

uz wasn’t the only woman in his life, nor even the only woman who claimed to be his wife. But the striking blue-eyed peasant woman was the first wife to the Mexican Revolution general, making her certificate of marriage the most valid, out of all the women Pancho Villa later married.

More important, she carried a lifelong wound of burying their infant daughter, Luz Elena, while he fathered children with other women, leaving her to raise many of them as her own.

The marriage certificate dated May 29, 1911, was more than just a symbol of pride for Doña Luz Corral; it became the first chapter of her life story which began on July 2, 1892. She was a living witness to what has been called “the storm that swept Mexico” in modern literature.

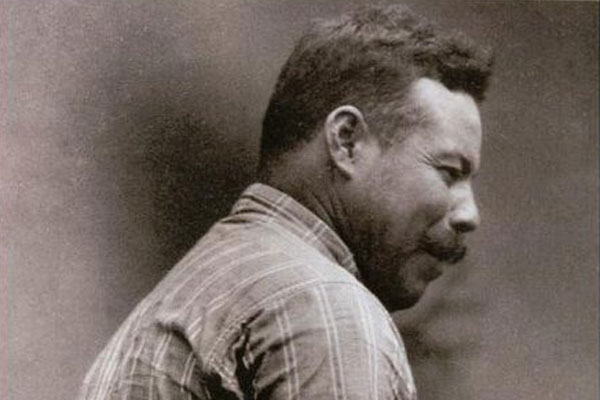

The Mexican Revolution was a sweeping panoply of brutal battles, criminal adventure and treacherous savagery. The Mutual Film Corporation paid Gen. Villa 20 percent of ticket sales to become Hollywood’s first revolutionary star of the newsreels.

But it was Doña Luz, whom he first saw when she was 18 in the village of San Andrés, who earned the role of Madre and matriarch. The courtship was short, contrary to her mother’s wishes, and it left Father Juan de Dios Muñoz aghast. After he asked the 32-year-old man to make his church confession, José Doroteo Arango Arámbula, the son of a sharecropper, reborn as Gen. Francisco (Pancho) Villa, responded that it would take days to list the sins on his soul.

In 1923, Villa was assassinated in his Dodge Brothers touring car in Parral, Chihuahua, leaving 31-year-old Mrs. Villa a widow—and with an orphanage on their property of some 50 children of all ages. Her life as the wife of the revolutionary was shattered, but she was a survivor.

Even though the government took the Villa Ranch near Canutillo, Durango, from Doña Luz for back taxes, they did not take the Villas’ 50-room mansion in Chihuahua City. For six decades Villa’s celebrity widow welcomed a stream of strangers and curiosity-seekers to La Casa de Villa, or Historical Museum of the Revolution, which was filled with artifacts of her dead husband.

For the equivalent of 25 cents, she provided an autograph, recited speeches in English while consulting an old notebook, and permitted visitors to examine remnants of the Mexican Revolution: Villa’s photographs, weapons, saddles and uniforms, and even his bullet-ridden car in which he was assassinated. Near the end of her life, Luz received visitors from bed, too weak to rise. She died at age 89 on July 6, 1981.

“Oh, I have no family of my own,” she told the El Paso Times in 1977, “but I have many families.”

Tom Augherton is an Arizona-based freelance writer. He recommends Luz Villa’s autobiography, Pancho Villa: In Intimacy (Chihuahua; Centro Librero Las Prensa, 1981). He also suggests visitors to modern Chihuahua City tour the Historical Museum of the Revolution, also known as Quinta Luz, to see Doña Luz’s great Villa collection.

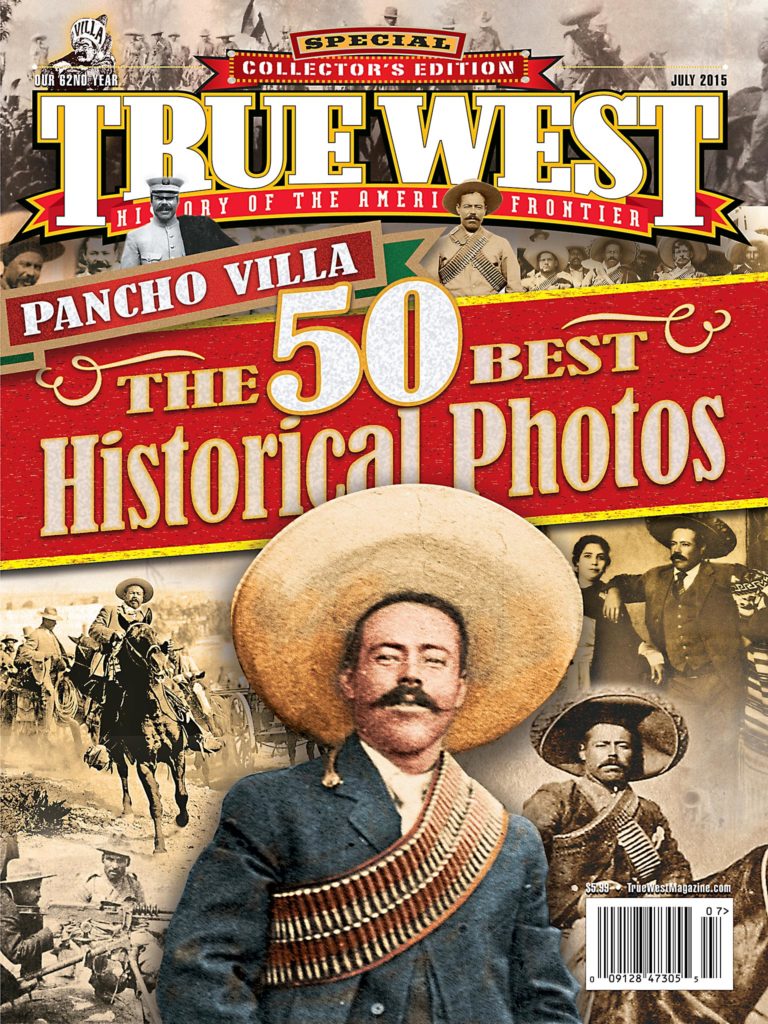

Photo Gallery

– Photos Courtesy Library of Congress –