“The most of the men I have killed it was one or t’other of us, and as sich times you don’t stop to think; and what’s the use after it’s all over?”

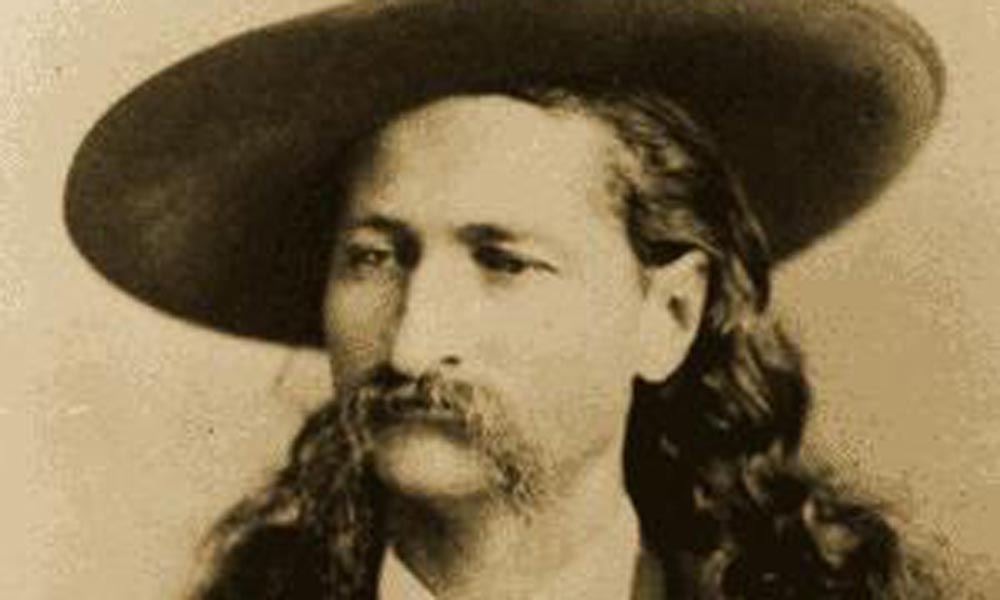

Wild Bill Hickok

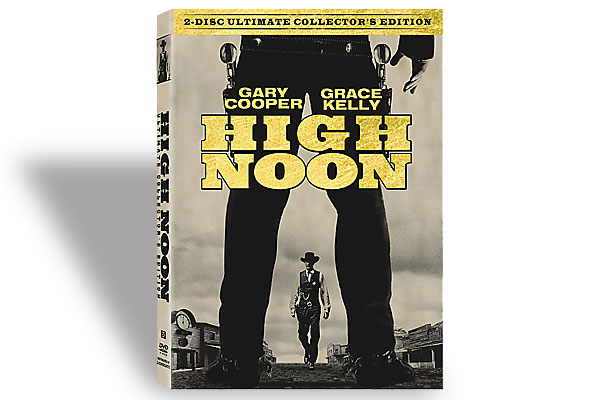

Shootouts at high noon, the trademark of western movies, were rare in the Old West. One stood a better chance at seeing horseflies in December or a shady lady in church.

A rare, but classic man to man gunfight in the street did occur on July 21st, 1865 when Wild Bill Hickok and an Arkansas gambler named Dave Tutt, faced off in the town square in Springfield, Missouri. They were rivals for the affections of a comely lady named Susanna Moore and that was a probable cause for the shootout. Trouble began one night when the two were engaged in a card game. Hickok ran out of money and put his gold watch on the table as collateral. He lost and went for more money to retrieve his watch. When he returned, Tutt refused to relinquish the watch. They exchanged threats and agreed to meet the next day and settle the matter with six-guns. The next evening around six p.m. the two antagonists met in the town square before a large crowd. Tutt tauntingly displayed the pocket watch belonging to Hickok. Both men jerked their guns and began advancing. At about fifty yards, they commenced firing. Tutt’s shot missed and Wild Bill put a bullet clean through Tutt’s heart. Tutt staggered back towards the courthouse and managed to cry out, “Boys I am killed!” before collapsing onto the square. Lucky shot? Probably, but it also had a lot to do with Wild Bill being cool under pressure.

Those kinds of gunfights were rare in the real West. If a man was gunning for another he was going to use every advantage possible even if it meant sneaking up and shooting him in the back. To square off and tell the other man to “draw” always gave the other guy a split-second edge. Usually, if one or the other didn’t have the edge the fight never got past the talking. “Code duello,” was for pulp westerns and motion pictures. Back shooting might have been frowned upon in the Code of the West but it certainly wasn’t unusual. Getting the drop on an adversary was all that really mattered. Actually, staying alive was what really counted. Deception was also part of winning the fight.

J.W. Buel wrote a highly fictionalized book Heroes of the Plains that tells the story of the time a drunken Bill Mulvey got the drop on Wild Bill in Hays City. Hickok looked over Mulvey’s shoulder and shouted, “Don’t shoot him boys, he’s drunk and doesn’t know what he’s doin’.” Mulvey was distracted just long enough for the marshal to draw his pistol and dispatch his foe. Good story but it didn’t happen that way.

In reality, Mulvey and some drunken friends were shooting up Hays City on the night of August 22nd, 1868. Mulvey had attempted to shoot several citizens when Hickok shot him dead.

A month later, on September 27th, Sam Strawhun and his pals were tearing up Jim Bitter’s Beer Saloon when Hickok was called to stop the ruckus. Strawhun came at him, some say he attacked with a broken glass, others a sixgun. Hickok shot him dead.

Wild Bill’s last gunfight occurred on the evening of October 5th, 1871 in Abilene. Sometime around nine o’clock Phil Coe and about fifty armed and drunk cowboys were in town whooping it up to celebrate the end of the trail-driving season. When Phil Coe and some of his rowdy friends approached the Alamo Saloon, he fired off his six-shooter. About that same time, Hickok arrived on the scene.

Earlier, he’d warned the cowboys against carrying firearms. He demanded to know who had fired the shot. Coe owned up to it, saying he’d fired at a stray dog that growled at him. He then jerked another pistol and fired two more shots, one striking Hickok’s frock coat and the other hitting the sidewalk between his legs.

Hickok pulled his guns and fired twice, hitting Coe in the stomach. At that moment, a figure appeared behind him carrying a pistol.

Hickok turned and fired, killing his friend Mike Williams. Visibly shaken, Hickok carried him into the Alamo where he soon expired. Coe lived for three days in extreme pain before he too, died.

Hickok’s days as a lawman were done.

Hickok was immortalized and fictionalized during the 1860s by writers like George Ward Nichols, Henry M. Stanley and in the 1880s by J. W. Buel that he’s so deeply ingrained in western folklore that it’s almost impossible to separate fact from fiction.

A complex man, Hickok was both feared and respected; loved and hated. He’s one of the most interesting of the gunfighters and one of the most analyzed and psychoanalyzed. He was no Two-Galahad but when he was provoked into killing he didn’t hesitate. The fight at Rock Creek with David McCanles and two others is debatable. The fight with Dave Tutt was a personal affair. He was tried and acquitted. Bill Mulvey, Sam Strawhun, Phil Coe and even poor Mike Williams occurred when he was acting in his official capacity as a lawman.

Legend has it Wild Bill killed between thirty-six and a hundred bad guys who dared to face him down. If all of the fictionalized and sensationalized stories of Wild Bill were actually true just about every day of his life would have been spent in some Hollywood-style gunfight at high noon. The actual number is closer to ten.

It’s difficult to separate the myth from reality with Hickok but one thing’s certain, his reputation as a mankiller who didn’t hesitate to shoot was usually enough to keep the peace in his towns.