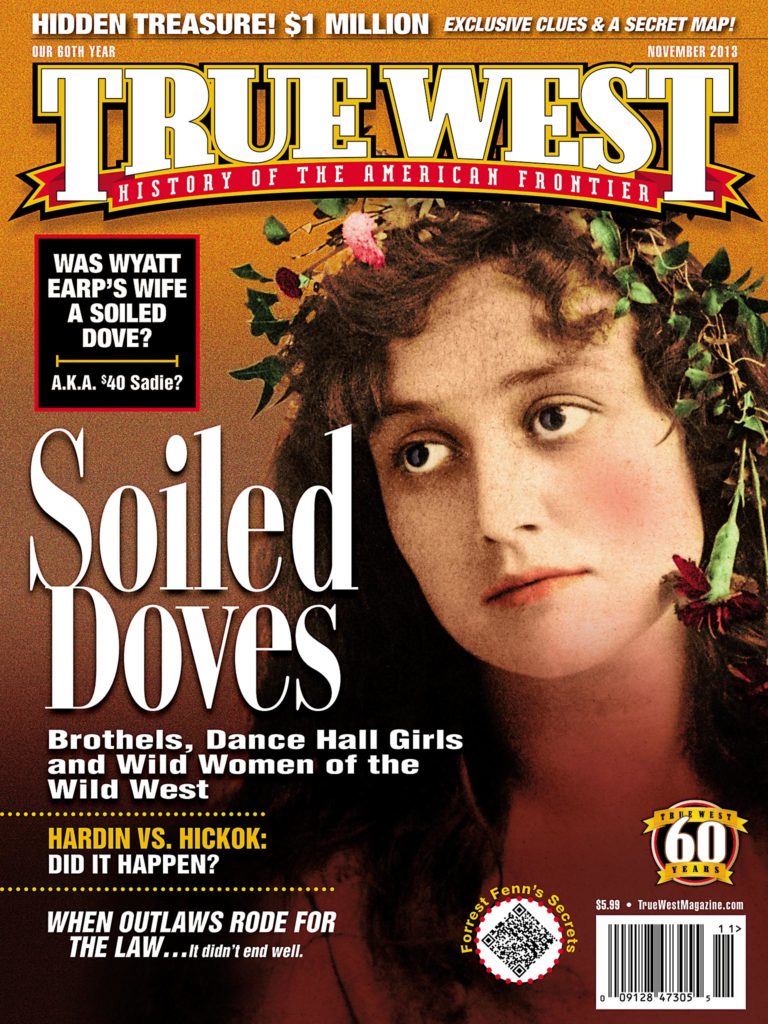

Bring up the intriguing subject of prostitution history in the American West, and you are sure to liven up a conversation.

Bring up the intriguing subject of prostitution history in the American West, and you are sure to liven up a conversation.

The thought of someone paying for sex diverts from societal and cultural ideals about how and when sex should be employed. It also brings forth a slew of questions, from how business was conducted to how the industry maintained its relationship with governments, big and small. In between are enough bawdy stories to make a sailor blush.

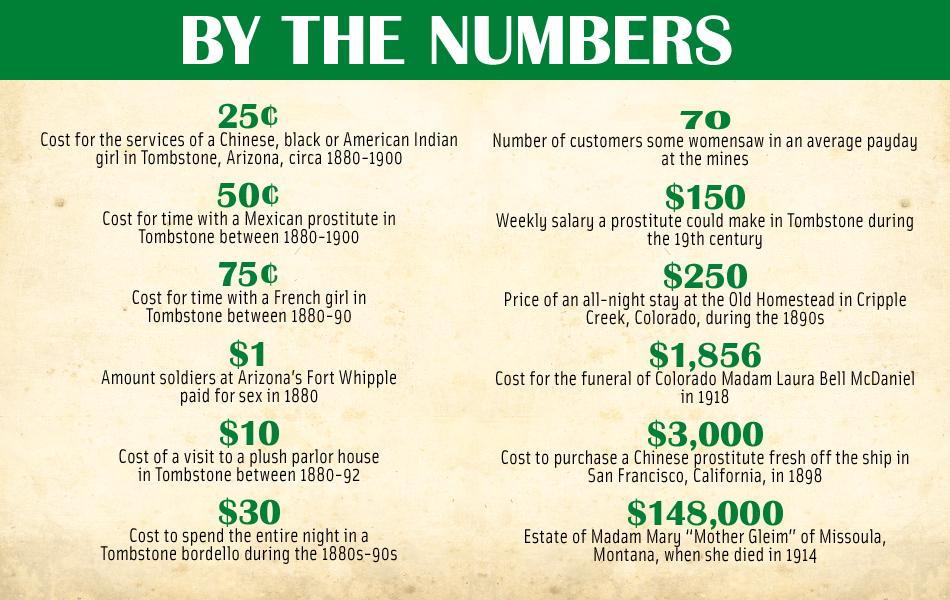

Although prostitution in the West could indeed be gritty and dangerous, the act was sometimes viewed as a healthy and integral part of life. In the days of the mountain men rendezvous, certain American Indians offered the sexual favors of their wives and daughters to their white guests. For instance, the Assiniboines of the Great Northern Plains commonly lent out their daughters for sex, always in trade for goods. The more the girls brought in, the greater the respect for them and their families. Not all tribes, however, allowed such sexual license.

One of the earliest cultured women to make her presence known in the West was Santa Fe’s celebrated courtesan, Gertrudis Barceló, known as Madam Tules, who first appeared in New Mexico in 1815. A married mother who began gambling professionally around 1825, Tules became single in 1841 and began romancing powerful men who could assist her in opening up her first brothel.

Tules served elite customers who included churchmen, U.S. Army officers and politicians. Newspapers noted her presence at social affairs, but descriptions of her fluctuated. An “old woman with false hair and teeth,” pioneer wife Susan Shelby Magoffin commented in 1846. “Young and blooming as we ever saw her,” the Santa Fe Republican reported the following year. Beauty was, indeed, in the eye of the beholder.

By the time the wealthy Tules died, in 1852, more and more male settlers were coming west, increasing the need for female companionship. In the harsh and lonely mining camps of the Rocky Mountains, men pined for women to the extent they would pay just to view or touch female undergarments, whether or not a woman was wearing them. Any man whose wife lived with him on the frontier was considered rude if he declined to bring her to social functions so she could dance with the other men.

Many of the few but brave women who made their way from the East looked for riches via the skin trade. Almost without exception, pioneer mining camps, boomtowns and whistle-stops became home to at least one or two soiled doves, if not a roaring red light district. Contributing heavily to town economies in the way of business licenses, fees and fines, a number of red light districts evolved into the social centers of their communities.

As the industry grew, so did the number of women who approached prostitution as a business profession. They did so with limited success. Prostitutes working above bars or in the seedier brothels rarely made enough money to retire and often ended their lives by suicide, overdose or illness. Gonorrhea, syphilis and chlamydia, potentially fatal maladies, ran rampant during the 19th century. An 1865 hospital report in Idaho City, Idaho, stated that one out of every seven patients was suffering from venereal disease. Botched abortions and murder rounded out the number of women who died while working as prostitutes.

Madams who had more control over their businesses fared better, but not by much. Witness the legendary Pearl DeVere, who arrived in Cripple Creek, Colorado, in 1893 and was soon running the most successful parlor house on Myers Avenue. When the first of two devastating fires in 1896 burned her brothel to the ground, DeVere had enough clout to borrow money from a New York investor and build an even better pleasure palace. Yet only a year later, in June, she overdosed on morphine following one of her Friday night soirees.

Madam “Belgian Jennie” Bauters of Jerome, Arizona, bought several brothels, one of which housed a lavish waiting room where “a trim maid in spangled short skirt and a revealing bodice” brought drinks to clients. In 1905, after Bauters had moved to Goldroad, southwest of Kingman, her ex-lover broke down her door and shot her. The man followed her out onto the street, shot her three times, left long enough to reload his gun and then returned. “Observing that she was not yet dead,” reported the Mohave County Miner, “he moved her head so that he could get a better shot and then deliberately fired the pistol into her head.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum were women like Mattie Silks, of Denver, Colorado, who stated, “I went into the sporting life for business reasons and for no other. It was a way for a woman in those days to make money, and I made it.”

The 19-year-old Silks opened her first brothel in Illinois before moving her “portable boarding house for young ladies” to Colorado. During her career, she owned several brothels, married at least twice and kept a lover.

She also had a reputation for excellent service and for sheltering the homeless. She once netted $38,000 running a bordello for three months in Dawson City, Alaska. Silks spent her wealth well, having only a few thousand dollars left to her name when she died in 1929.

Jennie Rogers purchased her first house from Mattie Silks, in 1880.

The Denver madam became famous after she shot her husband when she caught him in the arms of another woman, a few months after they had married in 1887. “I shot him because I love him, damn him!” she told the police. Her husband persuaded the authorities to release her.

Laura Evens of Salida, Colorado, was also known for her civic duties, even as she admitted to being a party girl. “I was pretty young when I first became a sporting woman,” she recalled, “and loved to sing and dance and get drunk and have a good time.”

During her years as a madam, before she died in 1953 at the age of 78 or 79, Evens sheltered abused wives and secretly paid the wages of men recovering from injuries on the job. “I doubt if anybody will ever know how many people Laura helped,” recalled a Salida politician. “She was an entire Department of Social Services long before there was such a thing.”

No matter their good deeds, prostitutes suffered blatant hypocrisy at the hands of local government. Towns demanded their red light ladies pay monthly fines, fees and taxes even as authorities staged raids and arrests. Sometimes towns drummed up business themselves. In 1908, officials in Salt Lake City, Utah, hired Dora Topham, the leading madam of Ogden (known as Belle London), to operate a “legal” red light district. The idea appealed to Topham, who viewed prostitution as inevitable: “I know, and you know, that prostitution has existed since the earliest ages, and if you are honest with yourselves, you will admit that it will continue to exist, no matter what may be said or done from the pulpit or through the exertions of women’s clubs.”

With approval from Salt Lake City, Topham oversaw construction of the “Stockade,” a high-walled city block housing several cribs, six parlor homes, a dance hall, saloons, a cigar store and a small jail cell. Up to 150 women could work in the Stockade at any one time.

The Stockade failed for numerous reasons. Local prostitutes refused to sell their properties and move into the Stockade under the watchful eyes of authorities, requiring Topham to hire most girls from out of town. Employees felt stifled by the stringent regulations. Customers were hesitant to be seen entering the premises. Plus, the government continued to stage raids to appease county, state and federal laws. Ultimately, in 1911, Topham was accused of working as a madam by the same officials who had hired her to do so. Topham had enough. She closed all of her brothels; by 1920, she had changed her name and moved to San Francisco, California.

Authorities took a different approach with Madam Laura Bell McDaniel of Colorado City, Colorado. Raised in Missouri, McDaniel married and divorced before landing in Salida, where she became a single mother. After her second husband shot a man to death in front of her, McDaniel left him and moved in 1888 to Colorado City, where she opened her first brothel. During her career, the “Queen of the Colorado City Tenderloin” weathered three fires, sent her daughter to school, ran several bordellos and hobnobbed with powerful businessmen. When she refused to shut down her business in 1917, authorities framed her for purchasing stolen liquor. She was acquitted in January 1918, but died the next day in a mysterious car accident.

With nearly all of America’s territories joined into a united nation by 1912, frontier prostitution began to come to an end. Three major factors contributed to its demise. The first was the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, formed in 1874 and gaining members as more and more wives came West and discovered what had occupied their men’s time.

Second were military posts that were tiring of their soldiers falling victim to drunkenness, fights, social disease and other maladies associated with prostitution. “Our health tests have proven that if a potential recruit spends twelve hours in Billings, he’s unfit for military service,” a military officer warned Montana officials in 1918. “I am talking about your line of cribs where naked women lean over window sills and entice young boys in for fifty cents or a dollar. Close that south-side line in twenty four hours or the military will move in and do it for you.”

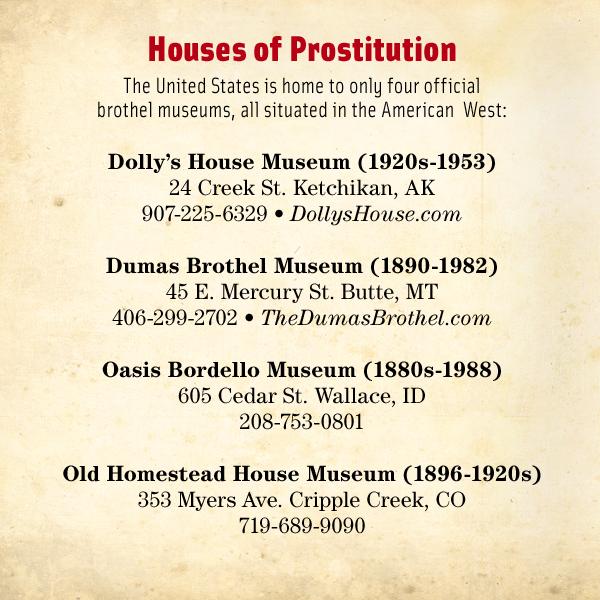

Finally, Prohibition in 1919 served to take the fun out of partying and greatly reduced the existence of red light districts in the nation. With the exception of rarities like the Dumas brothel in Butte, Montana, prostitution, at least as it was known in the frontier West, became part of a bygone era.

The marketing coordinator for Sharlot Hall Museum in Prescott, Arizona, Jan MacKell Collins has written two books about prostitution history in the Rocky Mountains. Her next book, The Hash Knife Around Holbrook, will be published by Arcadia Publishing in January.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– All images courtesy Jan MacKell Collins unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Jay Moynahan –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– Courtesy Chicago Review Press / Wanton West –