The Dakota and Chippewa songs could have been lost forever if not for a pioneer Minnesota woman who decided these American sounds must not be silenced.

The Dakota and Chippewa songs could have been lost forever if not for a pioneer Minnesota woman who decided these American sounds must not be silenced.

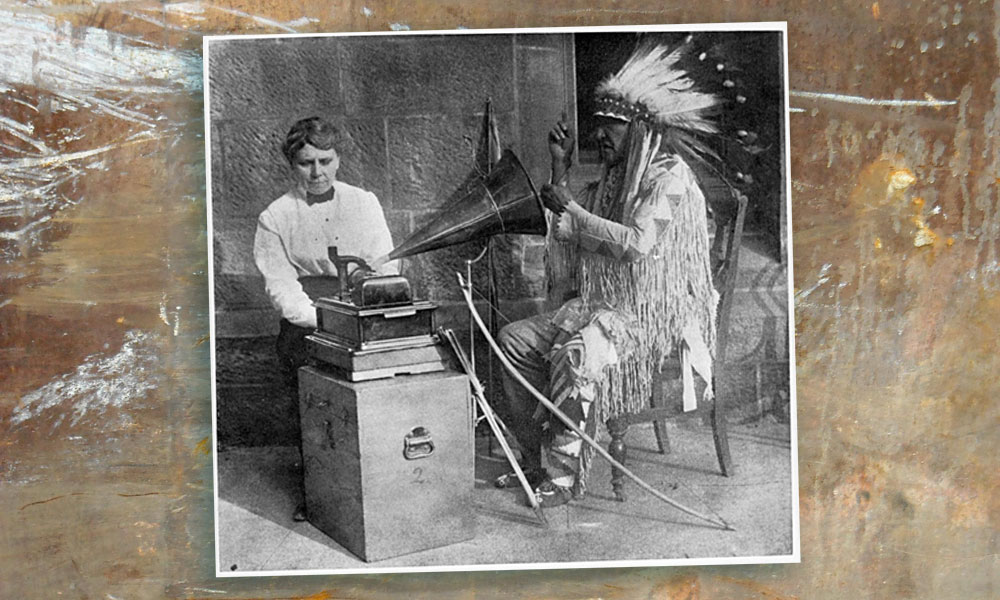

Thanks to Frances Densmore, early Indian music from throughout the country is preserved forever. She became one of America’s most important ethno-musicologists. She was a “song catcher.”

Sounds in the Night

Frances was just a girl growing up in Red Wing, Minnesota, when she first heard the traditional songs and drums of the Sioux Indians who lived nearby. She would remember the music went on well into the night. “In the twilight I listened to those sounds, when I ought to have been going to sleep,” she’d later report.

She had been born in the small, but fast-growing southeastern Minnesota town on May 21, 1867. Her family was prominent and prosperous, and Red Wing was becoming a thriving port for grain shipments. But it was still very much a frontier town. Tepees sat just outside of the town limits, and Frances grew up watching the Indians who came into town to shop or trade. She would remember she was always keenly curious about these “strange people.”

Her father Benjamin founded the Red Wing Iron Works. Her mother, the former Sarah Greenland, encouraged her daughter’s love of music and began her classical piano training early.

Frances was sent to Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio to study piano, organ and harmony. She graduated in 1887. Then she moved to Boston to study at Harvard with composers Carl Baermann and John Knowles Paine. While there, she became enthralled by the work of Alice Cunningham Fletcher, who had recorded the music of the Omaha Indians.

“The academic world was just beginning to recognize the importance of preserving the music of Indian cultures—many tribes, and their cultures, were fast disappearing because of the white man’s determination to ‘civilize’ them,” writes Bonnye E. Stuart in More than Petticoats: Remarkable Minnesota Women.

Frances returned home and taught piano for a couple years before she was drawn to Chicago for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. One of the “technological marvels” she saw there was Thomas Edison’s new, lightweight sound recording machine. Frances immediately saw how valuable this could be in recording Indian music, but it would take her years before she would actually own one.

“Stirred by all the exciting things she had seen at the world’s fair, Frances headed back to Red Wing and began to formalize her plan to study and record Indian music,” Stuart reports.

Frances studied Fletcher’s techniques—the latter had recently published a book—and they began corresponding. Frances also threw herself into studying Indian culture, folklore and history, information she utilized while giving public lectures. As Stuart notes: “It was not long before she was traveling to North Dakota, Illinois and New York to deliver her lectures.” In the beginning, to illustrate the cadence and feel of Indian music, she struck two sticks together to simulate a drum beat; by 1903, she beat an authentic tom tom, covered in deerskin, with birch-bark rattles from the Chippewa. Her enriched lectures became popular. She also wrote an article titled “The Song and the Silence of the Red Man” for the Minneapolis Journal.

Giving Their Songs

The groundwork for her own recordings started in 1905 when, accompanied by her sister Margaret, she set out to visit Chippewa communities near the Canadian border. This wasn’t a simple trip but, as Stuart puts it, “a bold adventure.” She would have to endear herself to the tribes and gain their trust to be allowed to listen to their sacred music at rituals few white people had ever attended. Obviously, she was a very persuasive woman. Through a guide, she was taken into the woods to the home of Shingibis, a medicine man she convinced to hold a religious ceremony. “The Indians sang well into the night, and Frances was so awed by the experience that she dared not take out her notebook to record the music she was hearing,” Stuart notes.

Frances would write down the sounds she heard, much like a composer writing out a tune, and she wrote articles about the songs. But she knew her second-hand descriptions did not have the power of the “authentic Indian voice.” She hoped one day to find an Indian who would trust her enough to sing into a recording machine.

She found him in Big Bear on the White Earth reservation. “She made arrangements to borrow the needed recording equipment from a local music store and persuaded the owner to let her set up a studio in his back room,” Stuart reports. “Big Bear’s songs filled twelve cylinder records, some of which are now on depository with the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.”

Frances, realizing she had too much work to do, appealed for funding from the Smithsonian Institution to help pay her expenses. She received the then-princely sum of $150, which allowed her to buy Edison’s Columbia Graphophone. Nothing could stop her now, and for the next 50 years, nothing did.

In its 1907 report, the Bureau of American Ethnology described her work like this: “The collection of phonographic records so far obtained is extensive, and the investigation promises results of exceptional interest and scientific value.”

Her popularity as a speaker continued to spread and in 1908 at a lecture in Washington, she finally met the woman who had inspired her life’s work, Alice Fletcher. She came away from their meeting rededicated to saving as much Indian music as she could.

In a 1912 lecture, she noted how important that was: “We have taken from the Indian his land and his hunting ground, but he is carrying his song with him, on his last long journey. Strange as it may seem the Indian is willing to give his songs.”

Her travels took her throughout the country as a “collaborator” with the Smithsonian. Her life’s work included 2,500 songs on wax cylinders from 30 different tribes, including the Chippewa and Dakota, Northern Ute, Papago of Arizona, Pawnee of Oklahoma, Winnebago of Wisconsin, the Seminole, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Yuman and the Tule Indians of Panama. Along the way, she also collected hundreds of Indian musical instruments that are housed in the Smithsonian.

In 1948, when she was 81, the federal government began preserving her work by transferring the songs from wax cylinders to permanent disks into what became known as the Smithsonian-Densmore Collection of Indian Sound Recordings. She personally supervised the project from her home in Red Wing. To bring her beloved music to an even wider audience, she selected her favorite Indian pieces for long-playing records for the public’s enjoyment.

She continued lecturing until shortly before her death in Red Wing on June 5, 1957. By then, she had not only preserved an amazing amount of native music and instruments, but she had also published more than 20 books and 200 articles on Indian music, customs and culture.

Among her most important works were the two-volumes on Chippewa music published from 1910 to 1913, and the Teton Sioux Music published in 1918—still considered as one of the best ethnographies of the Sioux.

“She can rightfully be called an American pioneer in ethnomusicology,” Stuart notes.