It was a situation that just asked for trouble.

In late June 1917, several locals of the International Workers of the World (“Wobblies”)—led by Big Bill Haywood—went on strike against mine operations in various Western states. Among their demands: safer working conditions and hard wage levels, instead of the sliding scale based on the price of copper and other metals. Bisbee, Arizona, was one of the targets. The strikers were radical, angry and spoiling for a fight.

The Wobblies weren’t big or terribly influential—in Bisbee, their members totaled about 400 of more than 4,700 miners employed in the Warren District. But they blocked traffic and threatened local officials and replacement workers. Even worse, the strike could have disrupted copper production intended for the WWI effort. Many citizens believed the union was anti-American—a belief strengthened by the fact that many of the Wobblies were immigrants from eastern Europe and Mexico. A common rumor: the strikers were pro-German or communists paving the way for a foreign invasion based in Mexico.

So on July 12, Cochise County Sheriff Harry Wheeler, backed by copper mine owners, led more than 1,000 vigilantes and special deputies in rounding up suspected members of IWW. (Company men often joked it stood for “I Won’t Work.”)

Louis C. Curry, 17, was there that day, taking remarkable photos of the event—most of them previously unpublished. His father, Joseph, served as chief clerk for the Calumet & Arizona Mining Company (the other mining concerns in Bisbee were Phelps Dodge and Shattuck). The copper companies were determined to show the Wobblies who was boss. The next day, The Bisbee Daily Review called the roundup a “blow at traitors, spies and anarchists that will make this clique tremble everywhere west of the Rocky Mountains.

Special thanks to Jason Farrier of Cave Creek, Arizona, for sharing Louis Curry’s photograph album with us. His father was a close friend of Joe Curry.

March to Warren

The roundup does not go smoothly. IWW man James Brew isn’t going to be taken; he shoots and kills Deputy Orson McRae before vigilantes gun him down.

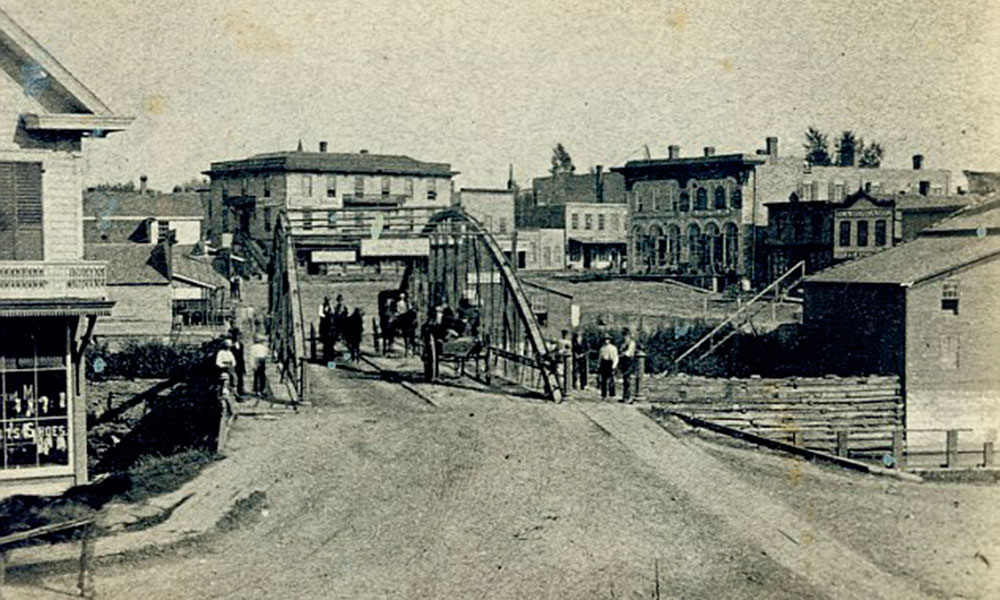

In all, about 2,000 people—including a handful of women—are captured. Many aren’t even miners or their supporters, but Sheriff Wheeler and his men aren’t taking any chances. A new problem crops up: there’s no place big enough to hold the Wobblies in Bisbee. So the deputies march the group to the nearby town of Warren, which has a ballpark.

Mexican Wobblies

Although Bisbee was known as a “white man’s camp,” a haven for white miners, in reality about 13 percent of its mine workforce was Mexican. The Wobblies demanded a raise for all “top men”—the unskilled surface workers who were almost all Mexican—to $5.50, just fifty cents less than white miners. In response to this infuriating stab at racial parity, vigilantes rounded up Mexicans indiscriminately. Unapologetic, Sheriff Wheeler asked federal investigators, “How could you separate one Mexican from another?” Thus lumped together, Mexicans made up more than a quarter of all the deportees.

Written by Katherine Benton-Cohen, an Arizona native who once lived in Bisbee and now teaches history at Georgetown University. Her book Borderline Americans on the history of racial conflict in Cochise County was published by Harvard University Press.

Fate of the Wobblies

On board the train, the alleged Wobblies are given food and water, but it is still a long and hot trip to Columbus, New Mexico, the terminal point of the deportation express. They don’t receive a friendly reception.

Authorities there refuse to take them in and force the train to turn around. It stops a few miles outside Columbus, leaving the deportees suffering in the summer heat. The situation is dire, so town fathers relent and allow the men to enter the Army’s Camp Furlong, just outside Columbus.

Many stay there for weeks. Eventually, some of the men return to Cochise County where they’re able to prove that they aren’t Wobblies. Others—about 100 or so—are arrested and put in jail in Tombstone. Most just drift to other areas. Bad feelings between mining companies and the unions are worse than ever.

With the passage of time, some mainstream officials and citizens begin questioning the actions taken in Bisbee. Family members of the deportees bring civil suits against those involved. (A 1919 case against the El Paso & Southern Railroad Company by Michael Simmons names J.E. Curry as one of the accused.) But these civil suits go nowhere. Sheriff Harry Wheeler and other deportation leaders also come under criticism, although they never admit to any wrongdoing.

The American labor movement is dealt a serious blow by the Bisbee Deportation; it will not recover for many years. The Wobblies, for the most part, remain just a fringe group, a footnote to history.