Dating to ancient times, commanders have wrestled with communications over distances and under combat conditions. The flashing shield, drums or other instruments, semaphores and other devices offered basic and, all too often, unsatisfactory results.

In an attempt to resolve this quagmire, Albert James Myer, of the U.S. Army Medical Department, devised a line-of-sight system that utilized waving flags and torches, which were simple and relatively reliable. This led to the creation of the Army’s Signal Corps, which had its baptism in fire during the Civil War.

More than a decade would pass before concerted efforts to harness this early-day wireless system came about, however, the British were the ones who took the lead. Sir Henry Mance, assigned to the Persian Gulf Telegraph Department of the Indian government, has been credited with inventing the heliograph (from the Greek words for the “sun” and “to write”).

After Mance secured a U.S. patent to protect his device in 1877, the Army shipped a pair of the instruments to its signal school. Despite successful trials, Myer, then chief signal officer, pronounced the devices as “auxiliary…to other and safer appliances….” His reservations stemmed chiefly from the heliograph’s dependence on proper lighting conditions and its inability to operate at night.

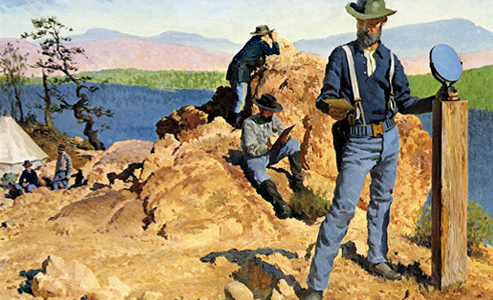

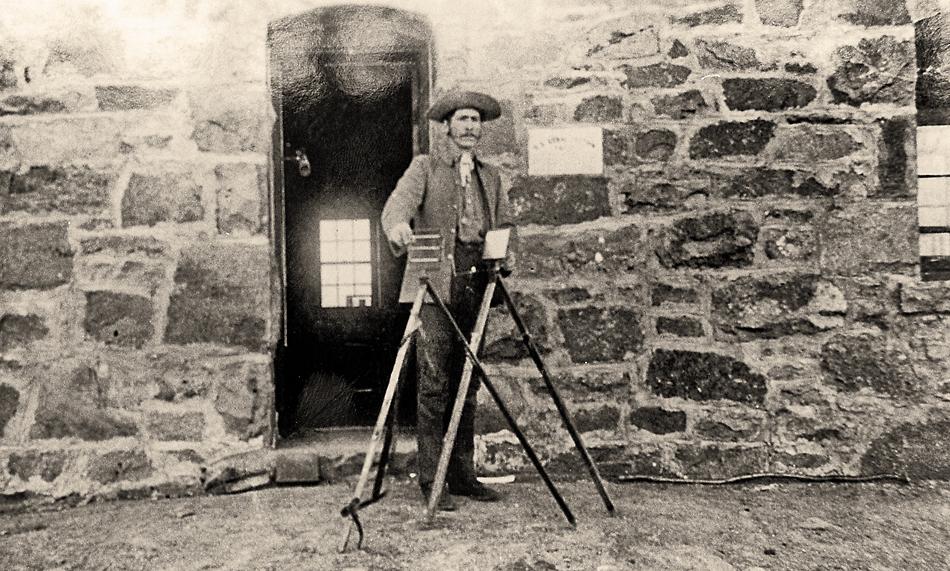

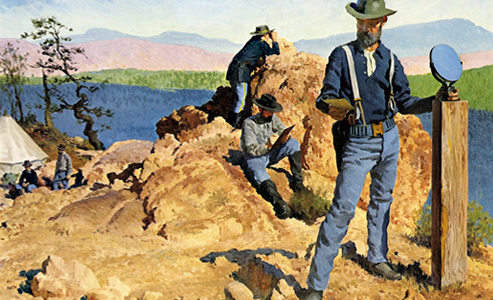

Regardless, the advantage was obvious. These heliograph models were fairly uncomplicated, being little more than circular mirrors set up on a wooden support. A key mechanism moved the mirror up and down to cause a flash that was visible to a receiver who stood on a faraway hill or peak.

Yet the Mance model did have some faults. The keys on early versions were regrettably clumsy and required frequent resetting of mirrors, which were forced out of alignment during use. Furthermore, the device was heavy, unwieldy and lacked interchangeable parts, making repair difficult in some instances.

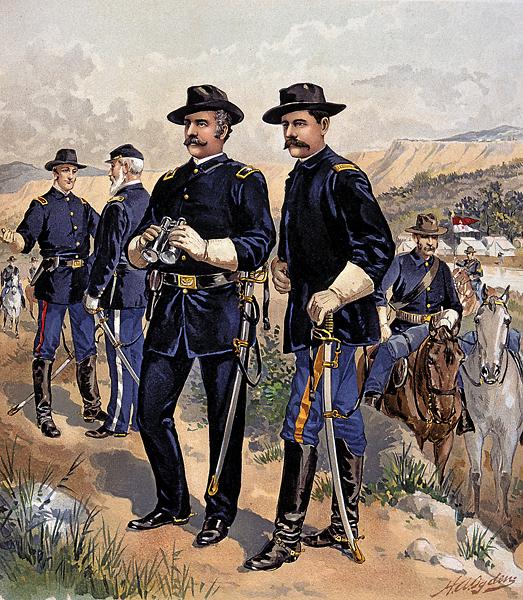

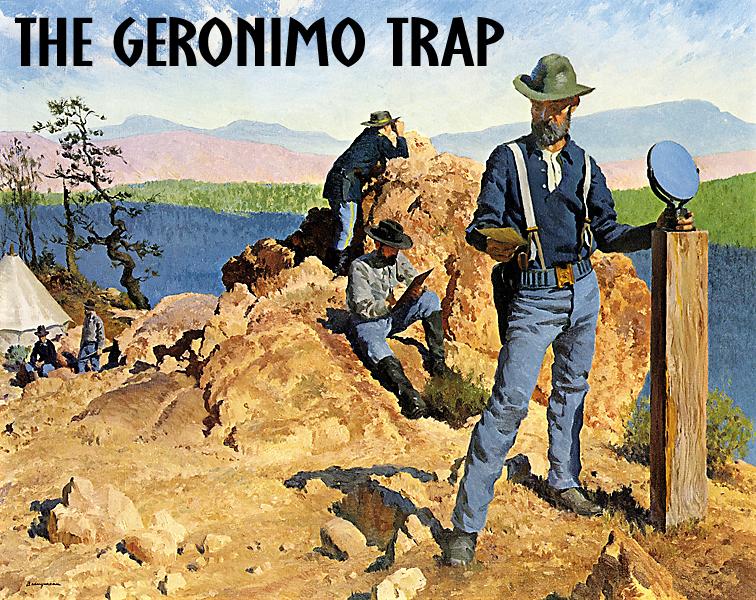

Over the next several years, efforts to improve the field instrument were undertaken. One senior officer who followed these advances, Brig. Gen. Nelson Miles, promoted the use of heliographs. During the final stages of the campaign to snare Geronimo, he directed that the “chief object of the troops will be to capture or destroy any band of hostile Apache Indians found in this section of the country.…” For this reason, he ordered that signal detachments “be placed upon the highest peaks and prominent lookouts, to discover any movements of Indians and to transmit messages between the different camps.”

The general’s innovation of a multi-station network was the most extensive effort to date at utilizing this instrument under combat conditions. His previous experience with heliographs, during his service in Montana in 1878-79, provided him with the background to inspire his scheme.

Although Miles’s memoirs indicated the heliograph was one of the mysterious methods that charmed Geronimo into ceasing his resistance, the Apaches knew about the heliographs and were not overawed by its powers. Miles, however, strongly believed in this technology.

Even as Geronimo’s band was sent to Florida as prisoners of war, heliographs continued as part of the military’s communications systems in the Southwest. For instance, during 1890, a large-scale exercise took place from Fort Whipple near Prescott, Arizona, to Fort Stanton near Ruidoso, New Mexico, along with branch lines to several posts and camps that were offshoots of the main network. The end result was satisfactory, though a number of shortcomings had surfaced during the trial. In totality, some 2,000 miles were covered with 33 officers and 129 enlisted men. The tests featured a 97-word message that was delivered in 22 minutes.

In one instance during that 1890 trial, a maximum sending distance of 125 miles from Mount Reno to Mount Graham was achieved on an unusually clear day. The chief signal officer of the Army and former Arctic explorer, A.W. Greely, traveled from Washington to observe. The United States Army and Navy Journal, the unofficial U.S. military sounding board of the late Victorian era, pronounced the maneuver he watched to be “by far the most important event in connection with the Signal Corps of the Army….”

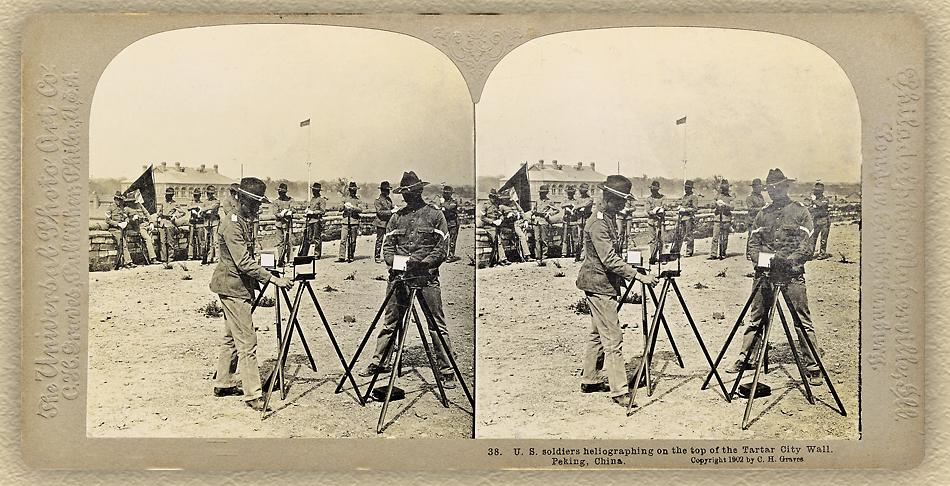

Such field conditions and extensive trials allowed the heliograph to prove its merit. The device continued as part of the Signal Corps’ inventory, and it was taken overseas during the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection. By 1908, one military journal indicated the heliograph was the “next most commonly used instrument for visual signaling by day,” with the exception of semaphore flags.

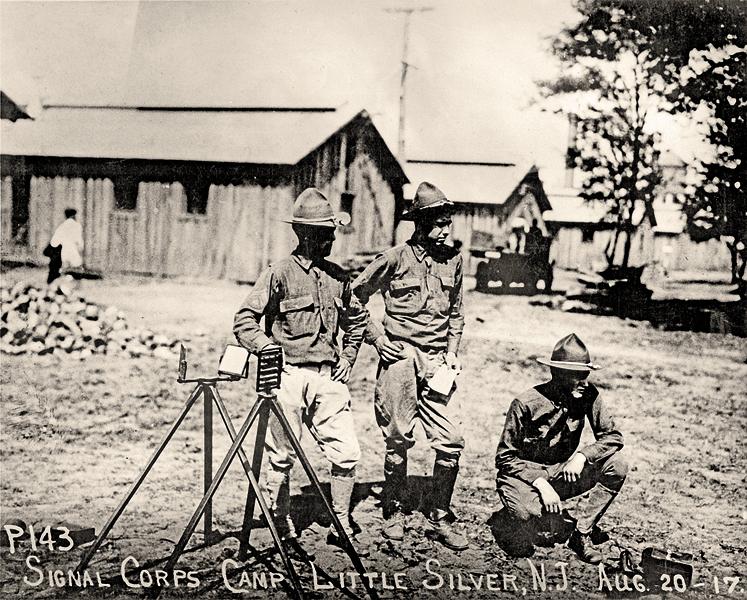

Even after other means of communications, such as telephonic devices, eventually replaced talking mirrors, these ingenious inventions remained a part of U.S. Army communications on the border with Mexico. Heliographs even found their way to the trenches of Europe during WWI before their usage at last came to an end.

John Langellier received his PhD in history from Kansas State University. He is the author of dozens of publications focusing on military subjects, and he has also served as a motion pictures and TV consultant.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Robert Winters Collection –

– Courtesy Robert Winters Collection –

– Courtesy Robert Winters Collection –

– Courtesy Robert Winters Collection –

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Robert Winters Collection –

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy National Archives –

– Courtesy Fort Davis National Historic Site –

– Courtesy Chase National Bank –

– Courtesy National Archives –