One of the best Wild West shoot-outs involved two Eastern artists. Instead of facing each other in the street, Charles Schreyvogel and Frederic Remington had it out in the newspapers.

One of the best Wild West shoot-outs involved two Eastern artists. Instead of facing each other in the street, Charles Schreyvogel and Frederic Remington had it out in the newspapers.

Their odd interlude is worth recounting on the 100th anniversary year of Schreyvogel’s death.

The two men actually had much in common. Both were born in 1861 and lived their lives in the East (Schreyvogel in Hoboken, New Jersey, and Remington in New York State and Connecticut). Without question, each was a talented artist.

But then the trails diverged. Remington spent significant time out West, trying his hand at ranching and bartending before picking up a pen and sketchbook. Many of his works were book or magazine illustrations of scenes he’d actually seen. He experienced notable success and recognition while still in his 20s.

Schreyvogel studied art in Europe. He always wanted to be an artist, and for years he searched for a genre that would capture his and the audience’s attention. While he created some illustrations, most of Schreyvogel’s work was strictly art (usually oil on canvas). He was in his 30s before he gained fame and fortune.

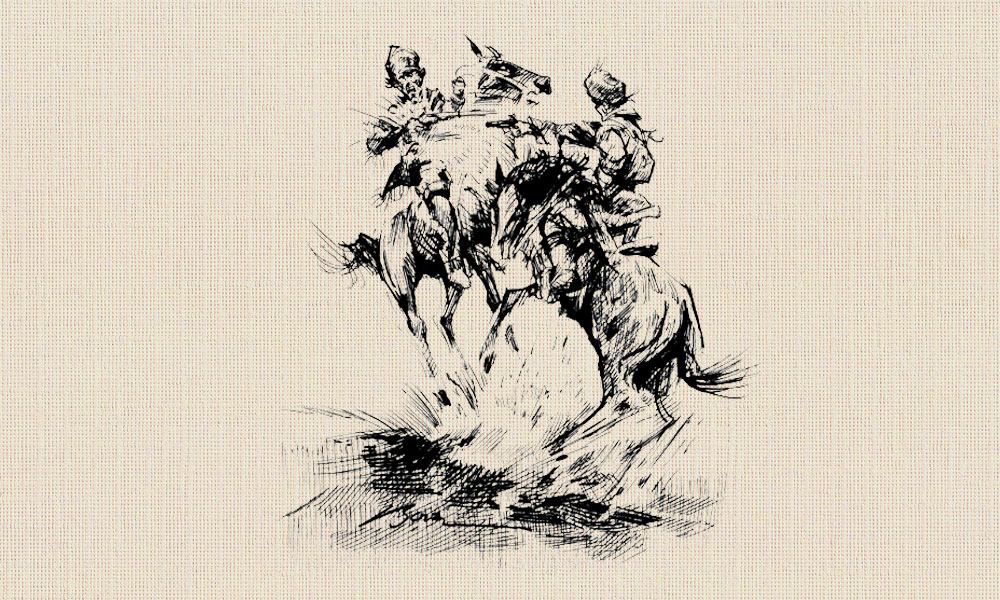

That was because Schreyvogel finally found his muse around 1890. One of his neighbors, Nate Salisbury, the business manager for Buffalo Bill Cody, introduced the artist to the Wild West show and to the showman himself. Inspired, Schreyvogel began painting Western scenes—similar to those by Remington—based on the Cody troupe. He portrayed lots of flash and action and derring-do and romance, but not the true West.

In 1893, Schreyvogel finally went West, spending five months in Colorado and Arizona, where he made sketches, interviewed cowboys and Indians and soldiers, and collected artifacts. Back in Hoboken, he painted on the roof of his apartment building.

Schreyvogel was meticulous and methodical. He wanted his paintings to be accurate as well as artistically pleasing. He spent months, sometimes years, on an individual piece (which is why he completed fewer than 100 works in his lifetime). That attention to detail—as well as his maturing talent—was recognized by a number of awards and honors around the turn of the 20th century.

Remington was not pleased about those recognitions, nor the comparisons of Schreyvogel’s scenes to his. “He was jealous,” says art historian Brian Dippie. “Remington didn’t like perceived rivals.”

Remington saw Schreyvogel as a phony. The Wild West was pretty much gone by the time Schreyvogel reached Colorado, while Remington had actually lived out West in the early 1880s.

In 1903, Remington saw that Schreyvogel had unveiled Custer’s Demand, which depicted an 1868 meeting between the famed soldier and some Kiowa chiefs. Remington told the New York Herald that the artwork had dozens of inaccuracies. He sat back and waited for the firestorm.

Remington was the one who got burned.

While researching the incident, Schreyvogel had obtained information from an officer who was present at the “demand” and from Custer’s widow. When the two sources saw the Remington critique, they—separately and without any encouragement from Schreyvogel—wrote to the Herald, essentially saying that Remington didn’t know what he was talking about. As a result, Schreyvogel earned even greater prestige.

For his part, Schreyvogel never publicly criticized Remington; in fact, he frequently stated that Remington was a great artist.

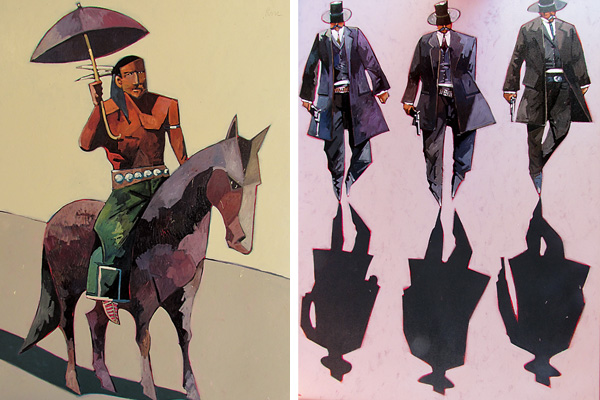

Arguably, Remington is the better-known artist in the 21st century. Dippie says a big reason for that is his prolific output. But in that 1903 dustup, Schreyvogel was the one left standing.