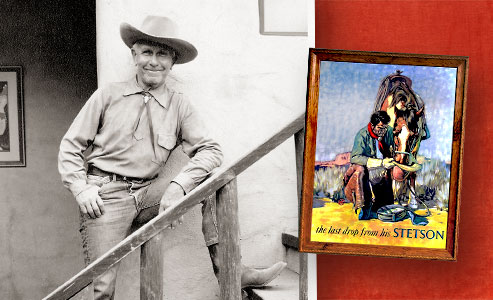

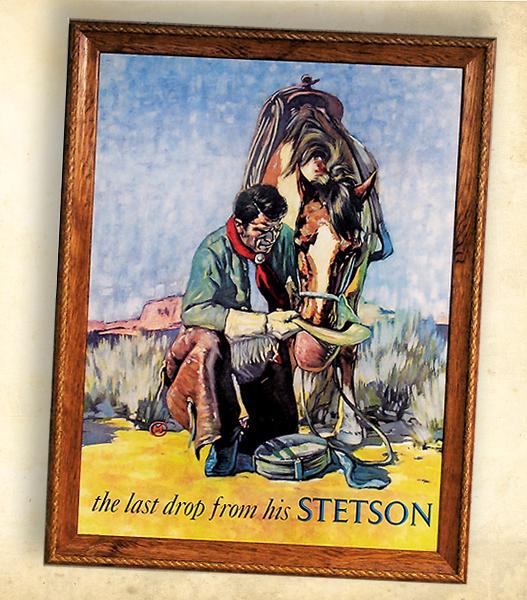

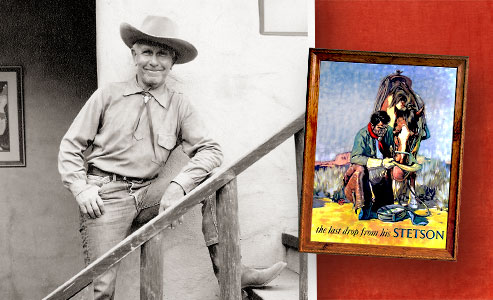

Did you ever look inside your Stetson and wonder who painted the poignant rendering of a cowboy watering his horse from his hat? In my humble opinion, the iconic Last Drop from His Stetson is right up there with the best works of Frederic Remington and Charlie Russell.

Did you ever look inside your Stetson and wonder who painted the poignant rendering of a cowboy watering his horse from his hat? In my humble opinion, the iconic Last Drop from His Stetson is right up there with the best works of Frederic Remington and Charlie Russell.

The artist was Lon Megargee, often characterized as “Arizona’s original cowboy artist.”

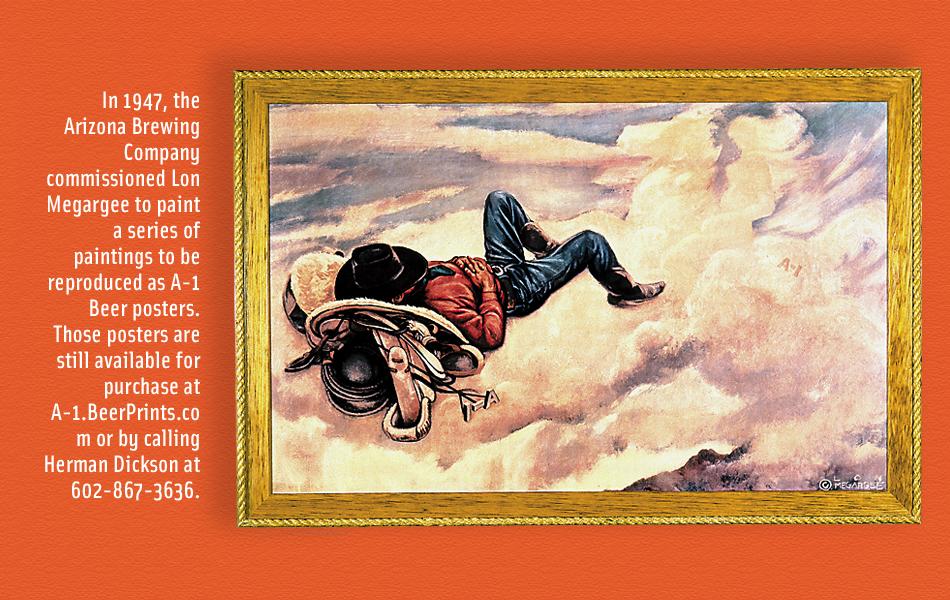

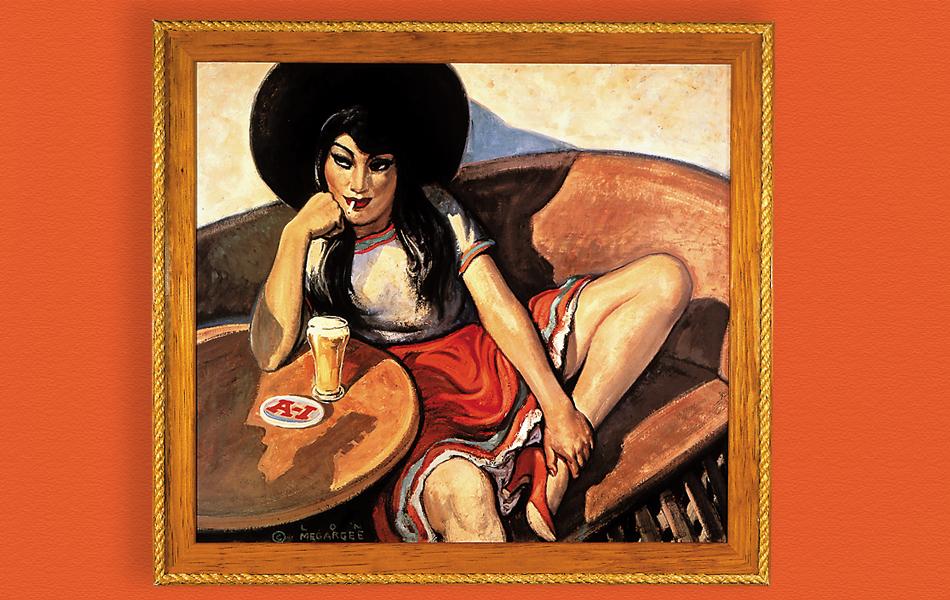

I first became aware of Megargee around 1949, when an A-1 Beer truck failed to negotiate a curve on Route 66 just east of Ash Fork. The truck flipped over, scattering beer bottles and promotional Western prints across a big arroyo. Word spread quickly around town as the locals flocked to the wreckage to salvage the bottles of beer that had survived the crash. The more cultured went home toting framed prints of Megargee’s A-1 Beer illustrations that had been en route for distribution to saloons in northern Arizona.

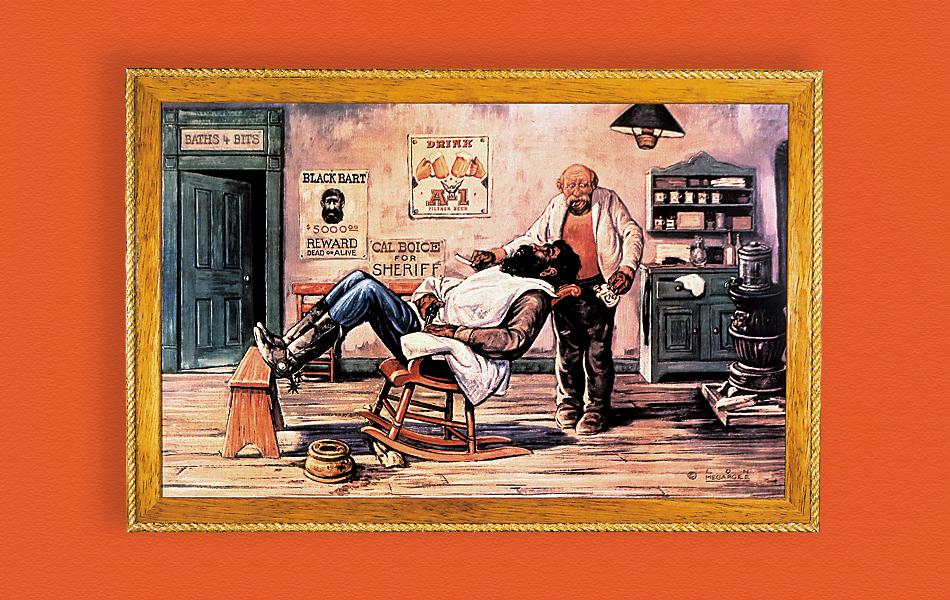

For a time, Black Bart (also known as The Barber and the Bandit) hung on the walls of many homes and businesses around town. I often wonder how many of those prints that now draw high-dollar prices were casually tossed into garbage cans over the years.

To borrow from the lyrics of Kris Kristofferson’s “The Pilgrim,” Megargee was a “walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction.” His whoppers could lead one down the path of plausibility, but the listener had to figure out where to get off.

Details of his life remain elusive due to the fact that, for various reasons, he tended to re-invent himself over and over. He also never let the truth get in the way of a good story. For instance, he claimed to be a self-made painter, but in reality, he had studied at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Los Angeles School of Art and Design.

Born Alonzo Megarge, he added another “e” to the end of his surname so he could connect with a prominent Philadelphia family that included the famous artist Edwin Megargee, who became his “cousin.”

He claimed his father was the only son of a wealthy Irish widow. While on a trip to Cuba, his father met and married his mother, a beautiful 16-year-old Cuban girl. His father died there in what was described as a “love fracas.” He told others he had followed in his father’s footsteps by abandoning the opulent life in an upper class family to another world, the American frontier.

Although he was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he claimed Tombstone, Arizona, as his birthplace. He even pulled the leg of his friend, Arizona Gov. George W.P. Hunt, who proclaimed Megargee as the “only artist of note who is a native of Arizona.”

During his checkered and fabricated life, Megargee would claim to be a lot of things, but one thing can’t be denied—he had talent. Beyond his formal training, Megargee displayed a unique style that was self-taught. His natural talent flourished during his career as an illustrator for newspapers and magazines. He also headed the art department at Lasky-Paramount Studios in Hollywood.

Born in 1883, Megargee, like many kids living in crowded Eastern cities, devoured the popular shoot-’em-up pulp Westerns. After attending Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, he became hellbent on living the life of his hard-riding heroes.

In 1896, at the age of 13, he hopped a freight train bound for Phoenix, Arizona. Once there, he worked various odd jobs, including milking cows and mending fences. He got his first chance cowboying when he took a job working cattle and bustin’ broncos at a ranch near Wickenburg.

During those early years, he took on a number of jobs, including fireman, policeman and card dealer. Presumably, he also performed as an exhibition roper with Arizona Charlie Meadow’s Wild West show.

He claimed to have owned the 51 Ranch (El Rancho Cinco Ono), north of Cave Creek, but went broke during a drought. He later called that a lucky break because bankruptcy got him out of ranching and into cowboy art.

Some truth can be found in his story. For instance, Tom Cavness may have been the owner of the 51 outfit, but Megargee did partner with him on some cows.

Like the hell-raisin’, devil-may-care cowboys he would go on to paint, Megargee liked to have a good time. The ladies found the ruggedly handsome man irresistible. He had an artist’s eye for feminine beauty. The women he painted extended him favors, and he acquiesced, if only for a short time. He was also adept at attracting pretty women who were financially able to support his lifestyle. His affairs were numerous and usually short-lived. Like many of his genre, Megargee was a rogue and a bold deceiver, marrying at least seven times and leaving a string of brokenhearted women in the wake (along with a few angry husbands).

He was also careless and footloose with his money. His financial resources were usually stretched to the limit. Throughout much of his career, Megargee was broke and in debt, scheming ways to fund his artistic projects.

His first taste of fame came when Gov. Hunt commissioned him to paint 15 murals for the state Capitol shortly after statehood in 1912, where many of his murals still hang. He and the governor became friends, but Megargee’s escapades sometimes put that friendship to the test.

Those murals and other artwork by Megargee were typical of those created by Western artists and illustrators of his time. His colorful landscapes, American Indians and cowboys depicted more of the romantic myth of the West, much the same as those acted out by Hollywood’s silver screen cowboys and portrayed in pulp Western magazines.

Despite the fact that he had experienced the real life of the working cowboy and its hardships, Megargee drew illustrations that promoted stereotypical scenes of the masculine mythic West. An incurable romantic himself, he painted it the way he saw it, and the way he liked it.

A complex and interesting character, who people either liked or didn’t, Megargee may not have been gregarious, but he was friendly to those he liked. Bolstered by his swaggering persona, he enjoyed gags, jokes and sharing a bottle with friends. He was always fun to be around, never a dull moment. Oren Arnold wrote in the October 1943 issue of The Desert Magazine, “Lon Megargee has had a good time in life, no matter where he happened to be.”

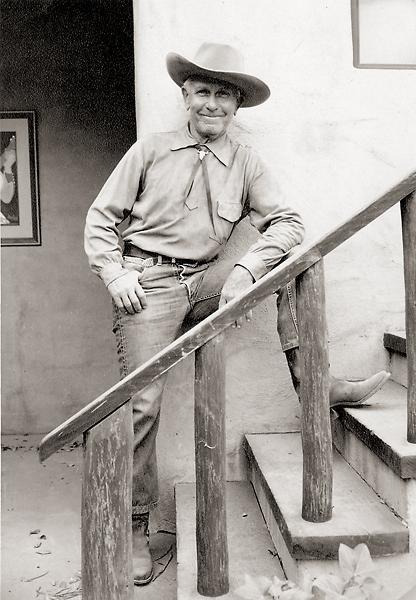

Like many artists, he lived a disheveled, Bohemian personal life, yet he was a rugged, self-made cowboy, from his boot heels to the top of his hat. What separated him from many in his genre is that Megargee didn’t just paint Western life, he lived it. Author Eve Ball wrote, “Lon Megargee was exactly what an Easterner thought a Westerner

should be.”

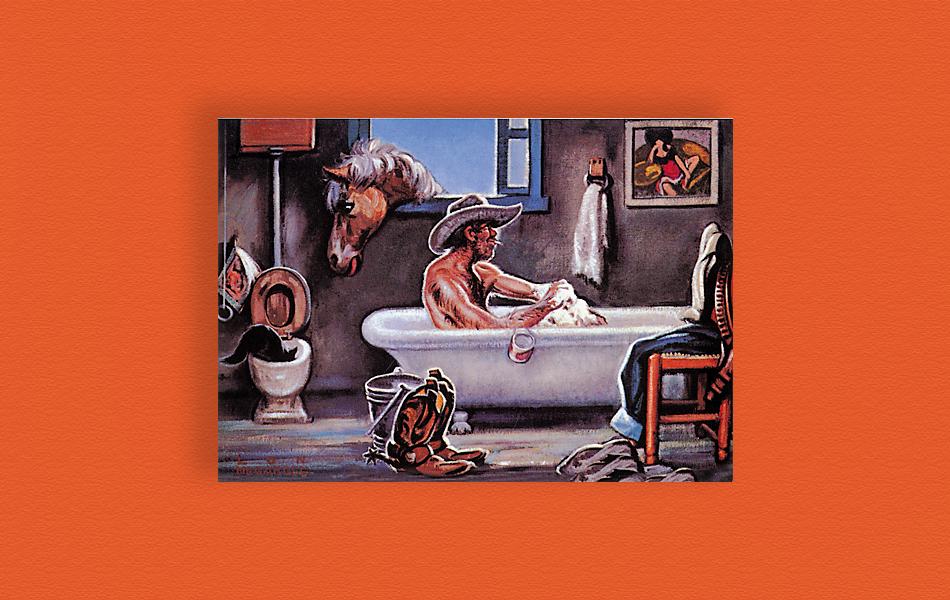

His sense of humor, as illustrated in Serenade, Cowboy’s Saturday Night and the A-1 Beer posters, is reminiscent of some of the works of the legendary Russell. I’m sure the two great cowboy artists would have enjoyed each other’s company.

Arizona’s small art community and limited cultural institutions in the 1950s made it difficult for an artist to make a living. Despite some financial success and artistic recognition, Megargee was always on the verge of being, in his words, “broke flat as a horseshoe.”

Over the years, he spent time in other places, including New Mexico, California and New York, but he always considered Arizona his home.

Although Megargee was a cowboy and an accomplished artist, he also designed and built several adobe, Santa Fe-style homes, some of which still stand today.

Old Pappy Time was beginning to catch up with Megargee by the 1950s. Fortunately, he met Hermine Summer Breitner, a writer and editor living in Cave Creek. Their marriage in 1952, his seventh or eighth, was a happy one. He settled down and took a more serious approach to his art. His wild and carousing days were behind him, and those turned out to be his most stable and productive years.

In 1956, he had his first major one-man show at the Grand Central Galleries in New York. He kept busy painting, right up to the end. Megargee went downhill after a serious auto accident in December 1959, dying of heart failure in Cottonwood, on January 24, 1960.

Every great artist desires to leave something behind that will grant him and his works immortality. For Megargee, his legacy is found in The Last Drop from His Stetson. This American icon is forever identified with Stetson hats; the image still graces the satin liners of nearly all Stetson hats, since 1924.

Megargee was a free spirit, and he certainly had his faults, but many of us can be forgiving and understanding of those creative souls who inspired us with their talent. He deserves to be placed right up there alongside the great ones.

In 2000, Marshall Trimble played Lon Megargee in a melodrama at Lon’s Hermosa Inn in Paradise Valley to raise funds for the restoration of his murals at the Arizona State Capitol. Megargee authority Herman Dickson provided information on Megargee’s life for this article. For further reading, check out Betsy Fahlman’s The Cowboy’s Dream: The Mythic Life and Art of Lon Megargee.

Photo Gallery

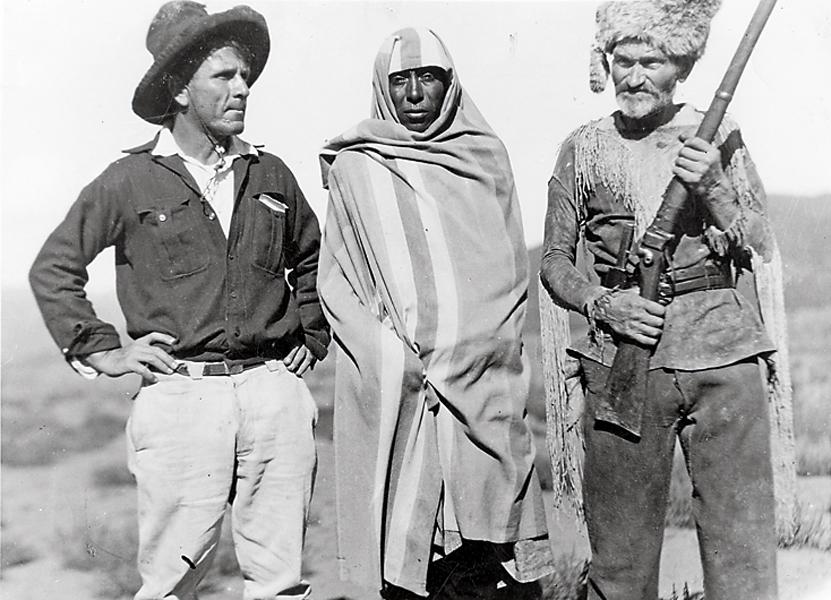

– All images courtesy Herman Dickson –