One of the most intriguing mysteries of the Old West concerns the disappearance of the Kansas murder family known as the Benders. From October 1870 until April 1873, a German family consisting of Ma and Pa Bender and their two grown children, quiet John and vivacious Katie, ran a murder inn seven miles northeast of Cherryvale in Labette County.

One of the most intriguing mysteries of the Old West concerns the disappearance of the Kansas murder family known as the Benders. From October 1870 until April 1873, a German family consisting of Ma and Pa Bender and their two grown children, quiet John and vivacious Katie, ran a murder inn seven miles northeast of Cherryvale in Labette County.

The family provided lodging where unsuspecting travelers became a grotesque statistic in the Bender apple orchard.

Their tiny, 16-feet-by-24-feet wooden shack had been built as a house of horrors, complete with a trapdoor under the kitchen table. Victims with split skulls or slit throats were dropped into a pit under the house, then dragged outdoors after dark and buried in the garden. During winter, when the ground was frozen, the family dumped mutilated bodies miles away on the snowbound prairie or tossed them during spring thaw into a local creek.

Between 1871-73, reports of missing travelers began filtering throughout the community. Neighbors became suspicious of one another, even to the point of organizing a vigilance committee. Then in March 1873, when Dr. William York went missing, an intensive search began. Dr. York’s brother Ed, an Army colonel living in Fort Scott, set out to find his missing brother.

After interviewing other families in the area, the colonel and his posse galloped into the Bender yard. Shortly after this visit, the family skedaddled; their wagon was found abandoned in nearby Thayer.

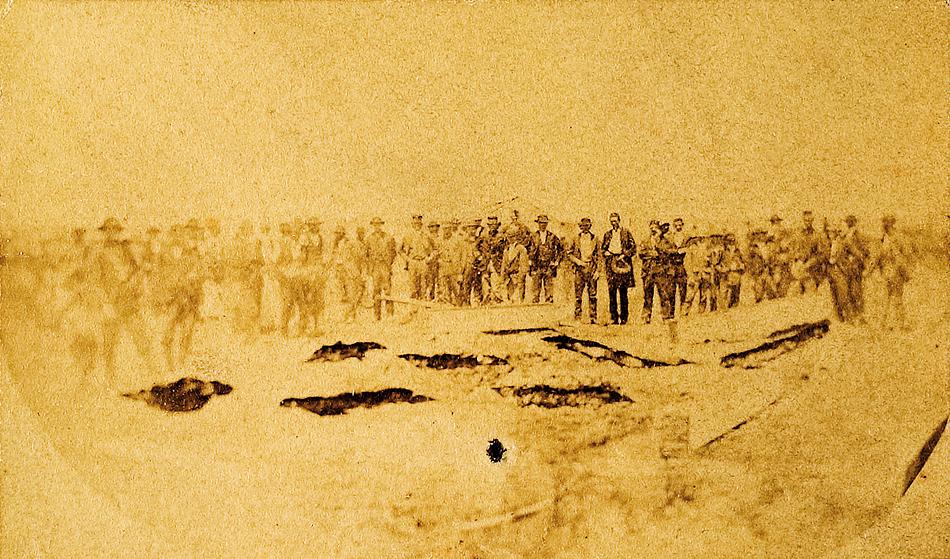

With the Benders gone, neighbors searched their property. The ghastly discovery of eight bodies, including the corpse of a little girl, plus the bloody, stench-filled cellar, told the grim tale. Then neighbors remembered finding additional bodies on the prairie the past winter that had been mutilated in much the same fashion. In addition, the wagon tracks near those bodies were of a peculiar design matching the tracks on the Bender wagon.

Kansas Gov. Thomas Osborn posted a $2,000 reward for the capture of the Benders; Dr. York’s other brother, Kansas Sen. Alexander York, offered a $1,000 reward. Professional and amateur sleuths alike took up the trail. Newspapers from New York to San Francisco to Paris, France, trumpeted the horrible news from Kansas, but in the end, the Benders seemed to have evaporated. Detectives tracked Ma and Pa to St. Louis, Missouri, where the trail went cold. Two of these same detectives followed John and Katie’s tracks to El Paso, Texas, near Mexico’s border, but they ran out of time as well as leads.

Why did the Benders commit these atrocities, making them among the first known American serial killers? Money. During their two-and-a-half years in Kansas, the Benders stole an estimated $4,500, plus made an unknown amount from the sales of the victims’ horses, buggies and wagons.

Historians believe travelers who lodged at the Benders’ inn confided to their hosts over dinner about their interest in buying land. Flirtatious daughter Katie, in her early 20s, likely encouraged the men to brag about how much cash they were carrying. Inside the dirty one-room shack divided by a wagon sheet, the unsuspecting visitor ate his dinner with his back against the brown-stained curtain. Then Pa would strike a blow from behind the canvas divider. Next, he cut the victim’s throat before dropping him into the cellar through the trapdoor. With the lawless Osage reservation near the eastern boundary of Labette County, John Jr. spirited horses, wagons, buggies, harnesses and valuables there to sell.

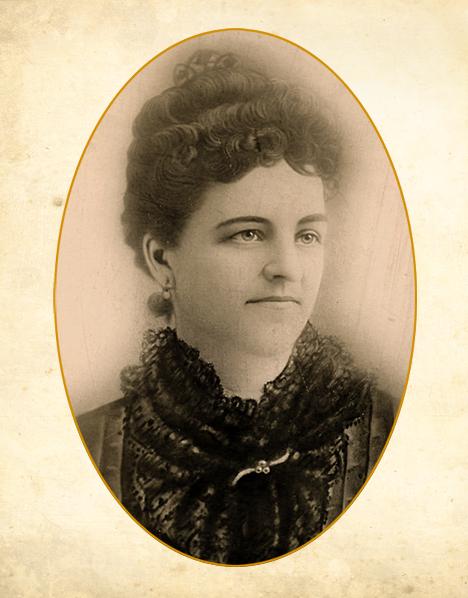

More than any other member of the Bender family, Katie has drawn the greatest curiosity. While writers have portrayed her as a knife-wielding temptress, perhaps Katie was actually a shrewd businesswoman with bigger fish to fry than chasing men around a desolate shack. Her long-term financial security was the real goal. With nerve and cunning, she played a clever game and won.

Now, 140 years after the killings, we think we have found Katie. Resting only a few yards away from gunfighter Doc Holliday, inside the Linwood Cemetery in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, is an imposing set of elaborate headstones surrounded by an iron fence. Do our eyes deceive us? Joseph Bender, 1843-1888. Beside him rests his wife, Katie Bender, 1846-1917.

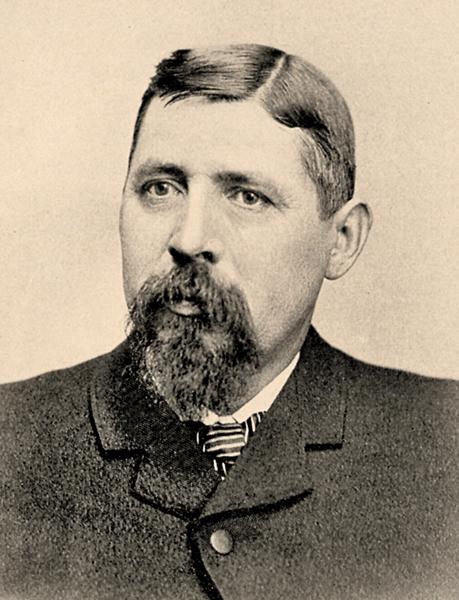

After an extensive search of courthouse and census records, newspaper articles and biographies at the local Frontier Historical Society, we learn that John Joseph Bender was born in Malsch bei Wiesloch, Baden, Germany, in 1843. He moved to the U.S. at the age of 21, settling in St. Louis, Missouri, where he worked as a blacksmith. Four years later, in 1868, he married Catherine Christiana Miller, who had emigrated while still a child with her family from Weinsberg, Baden, Germany. In her Colorado autobiography, Katie stated her father, George C. Miller, had served in the Missouri Home Guard during the Civil War and worked in the “grain business.”

John Bender and Katie Miller were married on January 4, 1868, in Hermann, Missouri, approximately 300 miles from Cherryvale, Kansas. Two years later, they lived in Cairo, Missouri. But then the two disappeared, until their arrival in Canon City, Colorado, in 1878.

In 1878, five years after the Benders had fled Kansas, John and Katie first appeared in Colorado. They traveled to several small towns in the territory where John continued working as a blacksmith. By 1886, the pair arrived in Glenwood Springs where they bought property on Seventh Street and opened a tavern.

On November 3, 1888, John, age 45, died of dropsy of the heart; his body was buried in the Linwood Cemetery.

Upon John’s death in 1888, Katie turned their tavern into what would be known for the next 30 years, until her death in 1917, as the Commercial Restaurant, located at 308 Seventh Street. In 1893, the local newspaper described the restaurant as a “large place, there being the spacious public dining room with its long lunch counter at one side and a number of private dining booths beside.”

Selling meals at 25 cents a plate, Katie miraculously accumulated enough money within the next 10 years to buy a number of store buildings, which she rented, plus four rental houses and property in New Castle, Aspen, Salida and other Colorado towns.

With the opening of the restaurant, did Katie finally have the opportunity to spend her Kansas blood money on rental property and other real estate without drawing suspicion upon herself?

She certainly had the means to travel. In the 1890s, the town newspaper, the Avalanche Echo, told of Katie’s trip back east to the World’s Fair. In 1895, she traveled to Europe to visit her old home in Germany and also to tour Great Britain and Switzerland.

On Valentine’s Day in 1903, The Glenwood Post reported, “Mrs. K.C. Bender has departed for Mexico where she will spend the remainder of the winter.” In 1903, seven years before the Mexican Revolution began, Mexico was an unsettled land, with public transportation limited to horseback or an ox cart. Acapulco hotels were still 30 years distant, and Cancun swimming pool resorts, 70. Did Katie visit friends across the border from her 1870s past, when she and John had gone hiding?

Katie never married again. Over the years, friendly news accounts told of Katie “sitting contentedly behind her cash register,” where she voiced her concerns with regards to politics and women’s suffrage. One news account, dated April 1905, gave her the distinction of being the only local person on the President’s train coming from New Castle (where her ranch was located) to Glenwood Springs, after “Mr. Roosevelt had gone out into the hills.” Are we to believe Katie was a personal guest of President Theodore Roosevelt on his train? Or did the friendly newspaper editor give this impression through a carefully-worded statement?

In 1909 came another interesting news item when Katie gave an interview railing against giving children toy guns. She claimed, “children had primitive impulses, the worse elements of one’s nature. When a combative idea is aroused, and then it is only a step to murder.” She concluded the interview with, “Love thy neighbor as thyself . . . and we’ll have fewer grown-up murderers.”

Of course, if this woman really was the Kansas murderess, why didn’t she and John change their last name? Bender was actually a common name in German communities, something like our modern-day Smith. Changing her last name would have aroused suspicion with her large family back home in Missouri, including three younger sisters and a half sister and brother. Plus, folks were looking for a brother and sister, not a husband and wife.

When Katie died of heart failure on January 20, 1917, at age 70, her body was buried in the grave site beside John’s. She named her brother-in-law executor of her estate. She left as much as $13,500 in cash to her various relatives, and in her will, she ordered all of her property be sold, including her home, the restaurant, some vacant lots, the ranch and other rental houses, so the money could be distributed among her sisters and their children, her church, a poor house in Missouri, a friend of her mother’s, plus $500 bequeathed to an organization called “Mother’s Appeal,” dedicated to home and family conservation.

Without an inkling of this woman’s past, Colorado’s Katie Bender appears to be a kind and generous woman whose life was beyond reproach. Was this bold, vivacious, fast-talking woman just clever enough to cover her bloody tracks by hiding in plain view?

Then again, perhaps two Katie Benders had been born in the same year, both German, with auburn hair, hazel eyes, a scarred left eye and adept at making money while spinning clever yarns. Both married to shy, reclusive, German blacksmiths named John and living within 300 miles of Cherryvale, Kansas, in 1870. Two young woman exactly alike who disappeared without a trace from 1873 to 1878.

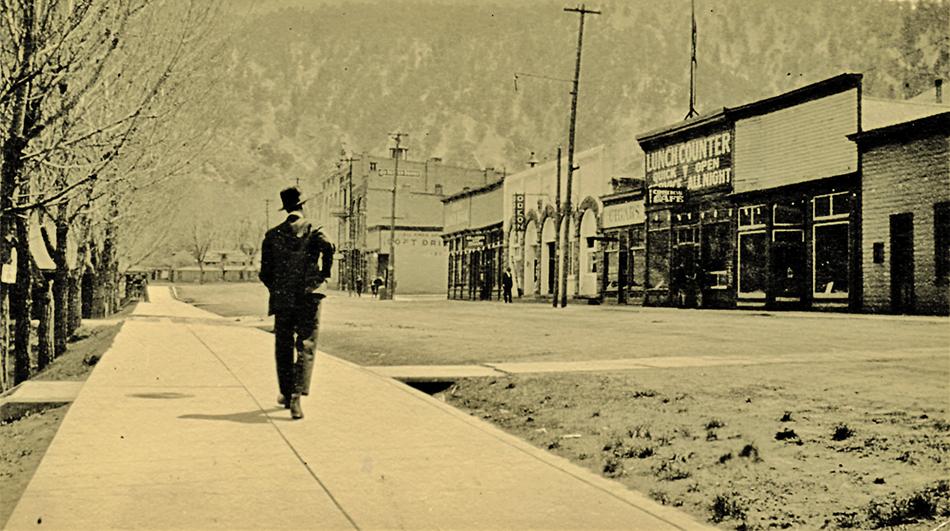

In an eerie photograph of a bleak afternoon in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, around 1917, a solitary man gazes toward the Bender restaurant. Is this image reminiscent of those lonely travelers who had walked along a trail on the Kansas frontier, eager for food, lodging and a bit of news, only to have met a terrifying death instead?

For 25 cents, the Bender restaurant became a convenient respite for travelers and for the community to gather, to form business contacts and friendships. Perhaps the only thing missing inside Katie’s Colorado restaurant was a bloodstained wagon sheet.

Phyllis de la Garza’s book Death for Dinner: The Benders of (Old) Kansas was published in 2004, reader Jan Peterson put the author on the trail of John and Katie Bender in Colorado.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, sold $425 bid, November 16-18, 2005 –

– Courtesy Cowan’s Auctions, sold $200 bid, December 19, 2011 –

– Courtesy Frontier Historical Society –

– Courtesy Frontier Historical Society –

– Courtesy Frontier Historical Society –