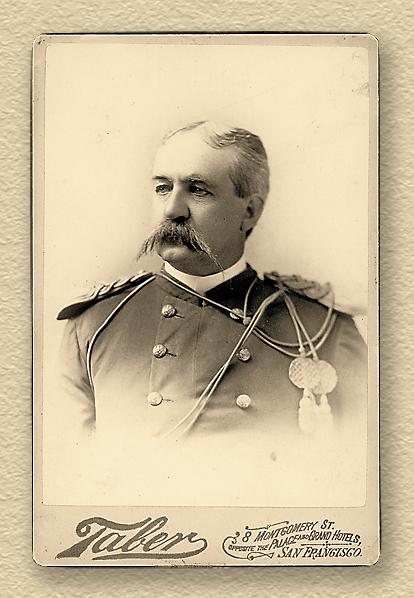

During the summer of 1886 in the midst of the Geronimo campaign in southern Arizona, Capt. Gustavus Cheyney Doane wrote dozens of letters to his wife, Mary, attempting to soothe her concerns about his safety.

During the summer of 1886 in the midst of the Geronimo campaign in southern Arizona, Capt. Gustavus Cheyney Doane wrote dozens of letters to his wife, Mary, attempting to soothe her concerns about his safety.

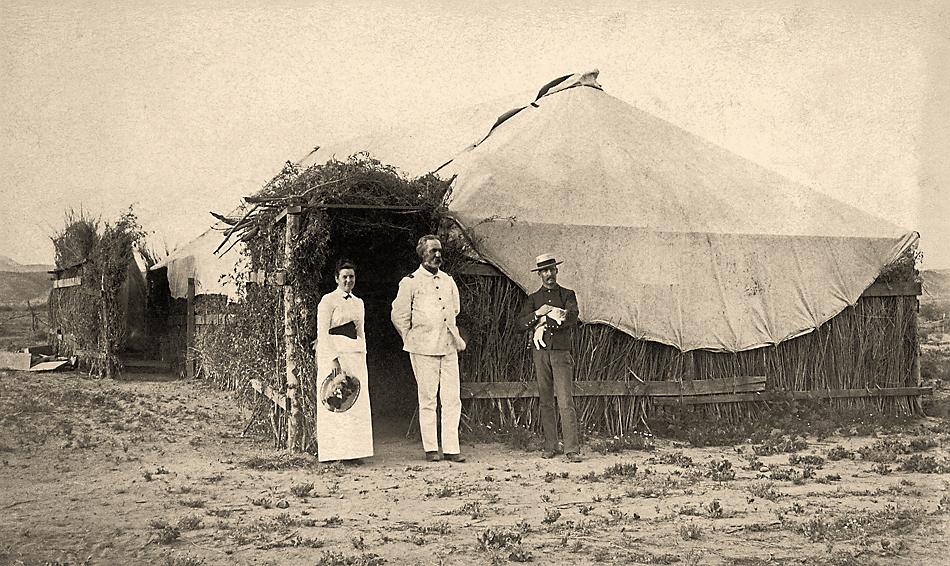

Doane commanded Company A, 2nd U.S. Cavalry, which, in August, had been posted at a sleepy heliograph station near Cochise Stronghold at the foot of the Dragoon Mountains.

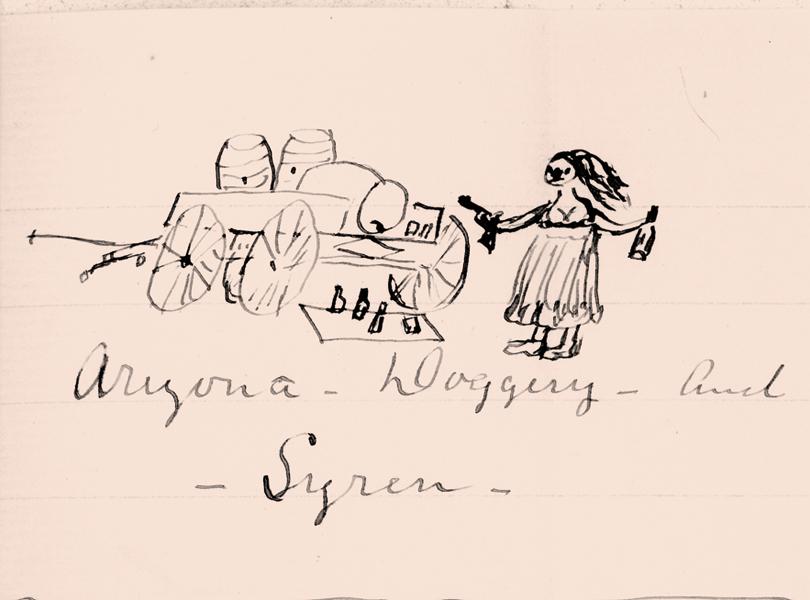

Of the more than 4,000 troops mobilized in Arizona, only a handful were actually needed to track Geronimo’s band south of the Mexican border, while the majority of troops, like Company A, wiled away their time occupying strategic points and providing a reassuring presence for area civilians. As Doane came to realize, the greatest danger faced by his own command that summer came not from hostile Indians, but rather from the visits of mobile whiskey and flesh peddlers who promptly arrived every payday, setting up open air brothels just beyond his camp’s perimeter.

“This country is full of tramps, thieves, and ten cent gamblers,” he complained to Mary. “Both whiskey and water are sold per drink at about the same price at roadside doggeries.”

In spite of his continuing reassurances, Doane never seemed to be able to convince his wife to stop worrying that summer. The more the captain wrote, the more things Mary found to fret about, ranging from her fears of his possible dalliance with prostitutes to rumors of a new war with Mexico. On August 18, Doane impatiently addressed both concerns in a remarkable letter that may not have comforted his wife, but certainly left a tantalizing clue for Earp family researchers. Doane’s message suggests the presence in southern Arizona of Wyatt Earp’s younger brother Warren at a time when his trail has largely been obscured to historians. Before we take a closer look at Doane’s cryptic reference to Warren, however, we need to review the circumstances surrounding its composition.

Tracking the Earps

While Doane and his men fought their campaigns against boredom, the bottle and the bordello that August, most of the surviving members of the Earp brothers had scattered far from the scene of their famous 1881 gun battle in Tombstone. Confirmed evidence of their precise whereabouts and activities is hardly complete.

Jim, the eldest, had accompanied the body of his murdered younger brother Morgan back to Colton, California, in March 1882. Although he and his wife, Bessie, wandered as far as Montana Territory during the intervening years, Jim likely returned to his parent’s hometown of Colton or nearby San Bernardino sometime prior to his listing in the 1887 city directory as the proprietor of the Club Exchange Saloon.

Virgil, grievously wounded by a shotgun blast in December 1881, also eventually returned to Colton. In February 1886, he, along with his father Nicholas, gave testimony in a Los Angeles breach of promise lawsuit and, in July, Virgil won election as the Colton village constable.

Wyatt had likely set up his residence in San Diego by the summer of 1886, although indirect evidence suggests he may have been in Trinidad, Colorado, as late as early January.

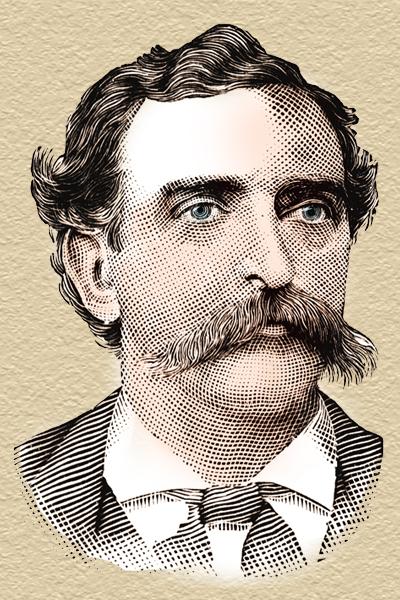

What has eluded historians is the 1886 location of the youngest Earp brother, Warren. We know he accompanied Wyatt on the Vendetta Ride in 1882, which led to a murder indictment against both men, and historians have placed Warren in Eagle City, Idaho, in 1884 when Wyatt and Jim were operating a saloon at that gold camp. In between times, Warren supposedly lived in Colton at the family home; in the summer of 1886, he presumably worked there as a “swamper” in his brother Jim’s saloon. However, according to Capt. Doane’s mention, Warren returned to the Tombstone area that summer, when he became involved with a Mexican controversy that had nothing to do with the chase after Geronimo.

The Mexican Trouble

Across the Rio Grande from El Paso in 1886, an American newspaper editor named Augustus K. Cutting managed to get himself into a load of trouble that resulted in escalating dangerous international tensions. Cutting published a newspaper on the Mexican side of the border that, in late June, attacked a rival editor in language guaranteed to bring a libel suit. When a Mexican judge ordered that Cutting publicly retract his comments, he did so, but he then walked across the bridge to the United States where he published the same slurs in the El Paso Herald.

Cutting found himself in jail after returning to Mexico, and his imprisonment for libel committed on American soil started a firestorm of protests across the United States. Hotheads from Pennsylvania to California called for a war against Mexico. While Mexican troops prepared entrenchments across the river from El Paso, volunteers offered their services for an invasion. One such group of would-be liberators gathered in the Tombstone area; Warren may have been among

their number.

As Cutting cooled his heels in a Mexican jail and excitable Americans howled for the opportunity to help liberate the newspaperman, Capt. Doane continued to battle the whiskey peddlers and prostitutes who assaulted his Cochise Stronghold camp. His strain began to show as the summer dragged on. When Mary expressed her concerns that her husband might be tempted, Doane dismissed her distress with crude jocularity. “What do you suppose I would have to do with those hideous old sluts that are humping soldiers out in the brush in reliefs?” he asserted, “If you could see their performances by moonlight once or hear their howls and jokes with the men at a distance of a few hundred yards as I am compelled to night after night you would probably be at least as disgusted as I am.”

If not placated by this blunt reassurance, Mary at least found something else to worry about—the rumors of a new war with Mexico over the Cutting affair. When Doane answered this concern, he left the clue regarding Warren that continues to puzzle Western historians nearly 130 years later.

“The Mexican trouble is all bosh. Cutting was properly imprisoned, at least so it begins to come out from the best sources. There is no movement [of troops] here in consequence of such reports and none expected,” Doane wrote. “The men who are offering to raise troops are mostly seedy scallywags of whom one is the man who keeps the little doggery in the bush in my camp, a man named Broad from Tombstone and the most contemptible character I ever saw, Earp of Colton, a murderer who was driven from Tombstone, is another.”

Doane’s letter gives plenty of room for interpretation and deserves a closer look. “Broad” is no doubt Frank “Bloody Frankie” Broad, a Tombstone saloon owner, unofficial enforcer in the city’s red light district and a successful candidate for the area’s judicial district constable that summer. Broad’s resume sounds remarkably similar to the well-known activities of all the Earp brothers during their various careers throughout the West, making Broad a logical companion for someone like Warren.

That Warren is the particular brother Doane referred to is also logically established. Of all the surviving brothers, Warren, Virgil and Jim were the most widely associated with the village of Colton, but only Warren was still under indictment in 1886 for the murder of Frank Stilwell in Tucson at the beginning of the Vendetta Ride in March 1882. The ambiguous wording of Doane’s sentence could imply that Warren was Broad’s partner in the doggery business, but it could also suggest that Warren was simply involved in organizing Cochise County volunteers for the supposed invasion of Mexico. Regardless, the sentence establishes that Warren was in the area because of Doane’s specific choice of words, “the most contemptible character I ever saw.”

“Earp of Colton”

The captain was never one to use words carelessly. He held a reputation as one of the best report writers in the frontier Army, and his published description of the 1870 Yellowstone expedition played a key role in the establishment of America’s first national park. If Doane told his wife he saw “Earp of Colton,” he meant exactly that. Although the Tombstone newspapers do not report on any Mexican invasion volunteers organizing, a blurb in Prescott’s Arizona Weekly Journal-Miner confirms that 28 unidentified Tombstone men had offered themselves for such a purpose on August 18, the same date that Doane wrote his letter.

Tombstone newspapers gave Broad plenty of notice that summer for his “supply” efforts directed at soldier outposts, as well as his enthusiastic activities in Tombstone’s anti-Chinese league. Perhaps his role in calling for volunteers was so well known, the paper found it did not merit specific mention. Of course Warren, if in the area, had his own reasons for avoiding newspaper notice.

Was Warren involved in the purveying of vice to soldiers in southern Arizona during the Geronimo campaign, or was he just an enthusiastic volunteer for an imagined invasion of Mexico? From Capt. Doane’s testimony, either conclusion seems possible. Unless other evidence regarding Warren’s whereabouts in the summer of 1886 comes to light, this statement by Doane supports the notion that Warren returned to Arizona much earlier than anyone has proven to date.

Professor Kim Allen Scott is the university archivist at Montana State University Library in Bozeman. His in-depth biography of Capt. Doane, Yellowstone Denied, was published by University of Oklahoma Press in 2007.

Photo Gallery

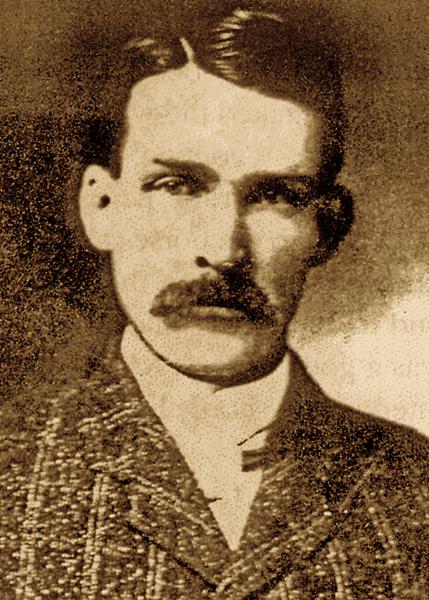

– Courtesy Montana State University, Gustavus C. Doane Papers –

– From The Biographical Review of Prominent Men and Women of the Day by Thomas W. Herringshaw, published in 1888 –

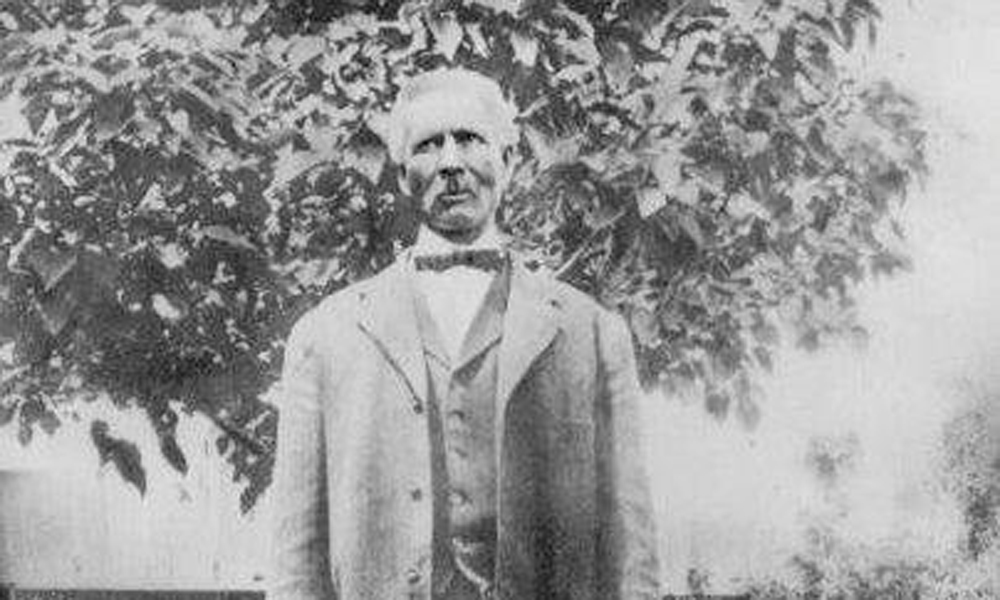

– Courtesy Montana State University,Gustavus C. Doane Papers –

– Courtesy Museum of the Rockies at Montana State University –

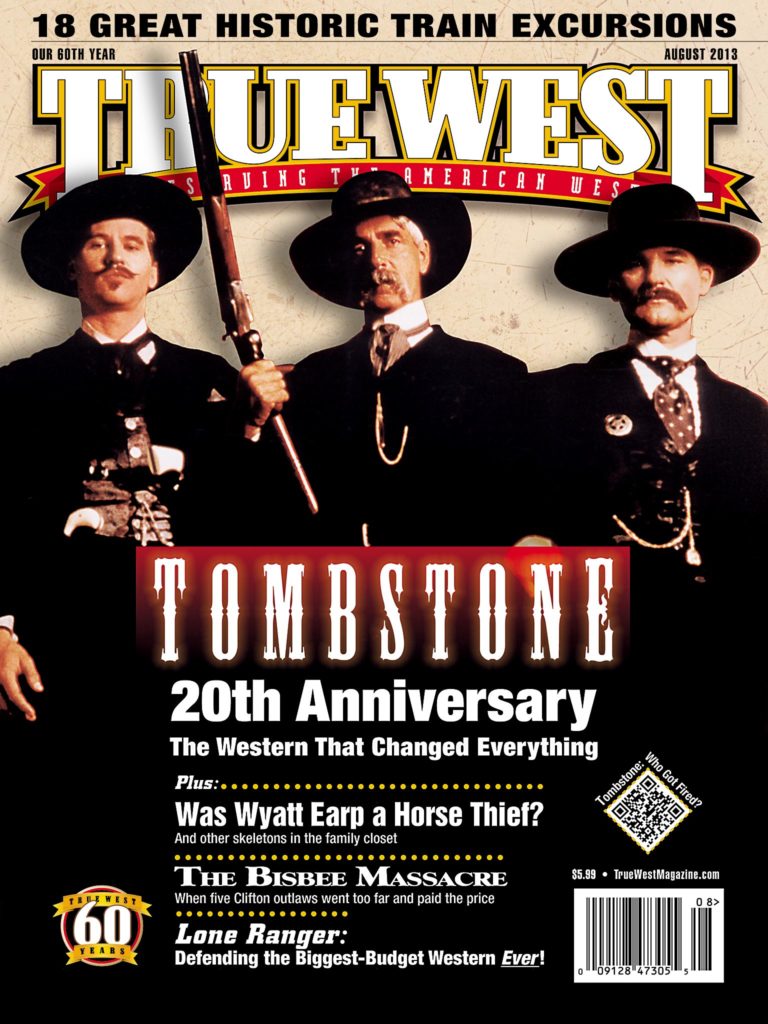

– True West Archives –