Beginning July 18, 1881, with telegrams from the Gazette and Optic newspapers in Las Vegas, word spread throughout New Mexico Territory and the United States that Billy the Kid was dead, having been killed the previous Friday morning by Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom in Fort Sumner.

Beginning July 18, 1881, with telegrams from the Gazette and Optic newspapers in Las Vegas, word spread throughout New Mexico Territory and the United States that Billy the Kid was dead, having been killed the previous Friday morning by Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom in Fort Sumner.

After a brief coroner’s jury inquiry confirmed the corpse as the Kid’s, his remains were buried that same morning.

Within days, the news shifted to Garrett’s efforts to collect his $500 reward for his “capture” of the Kid and to various territorial towns gathering funds to pay for Garrett’s expenses and to offer a gratuity for ridding them of the Kid. As far as the world was concerned, the Kid’s remains were resting intact in the old U.S. Army cemetery three quarters of a mile from that bedroom. But was all of him there?

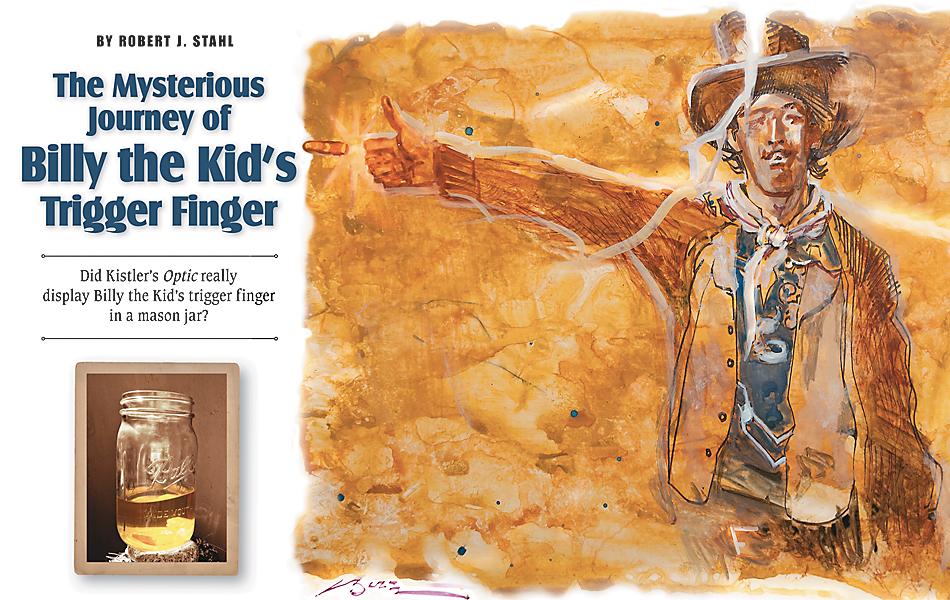

The “Fatal Finger”

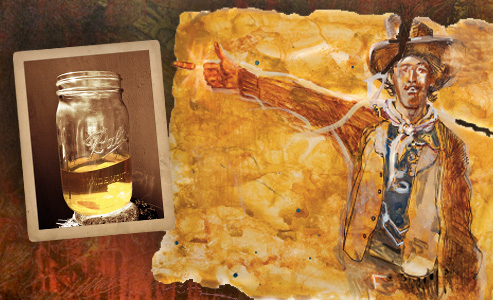

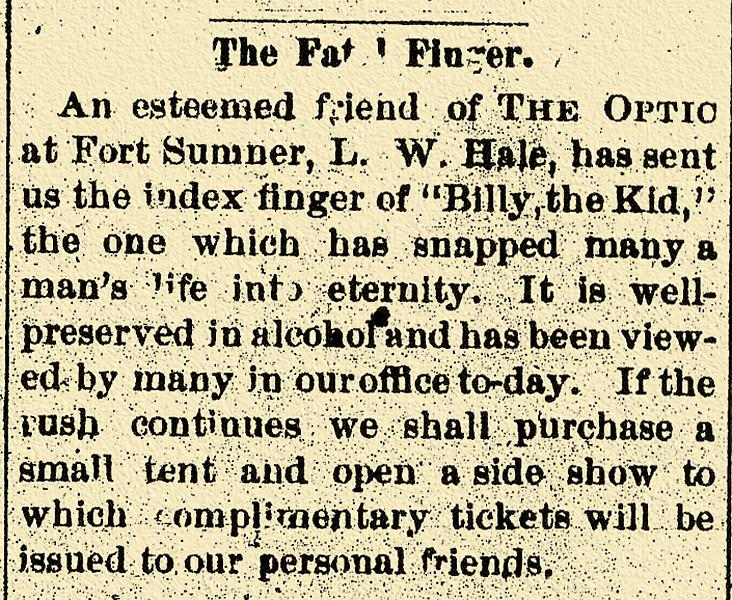

On July 25, eleven days after Billy was killed, the Las Vegas Daily Optic printed the following, under the headline “The Fatal Finger:” “An esteemed friend of THE OPTIC at Fort Sumner, L.W. Hale, has sent us the index finger of ‘Billy the Kid,’ the one which has snapped many a man’s life into eternity. It is well-preserved in alcohol and has been viewed by many in our office to-day. If the rush continues we shall purchase a small tent and open a side show to which complimentary tickets will be issued to our personal friends.”

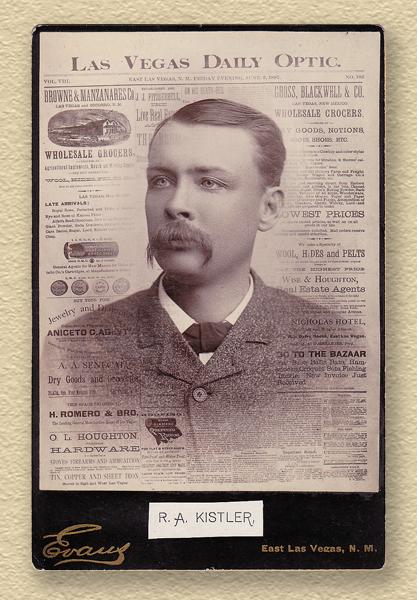

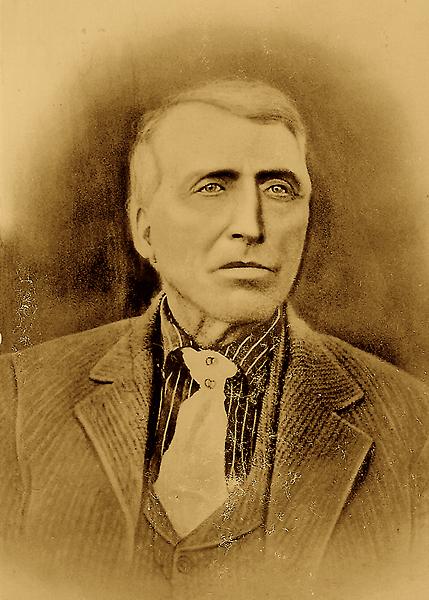

Russell A. Kistler, owner and editor of the Optic, had wasted no time in telling the world that he had the Kid’s trigger finger. Even though less than 40 telephones operated in the town at the time, the story spread like wildfire by word of mouth. By the time the paper went to press at about 3:30 p.m., dozens of people had made it to the Optic office near the railroad depot in east Las Vegas to gawk at the trigger finger of the young man whose death they had celebrated days earlier. For those hundreds of citizens who had seen the Kid on their streets, this was the last opportunity most had to see his remains.

Kistler must have had second thoughts about the tickets, as none were printed, sold or distributed; no later issue of the Optic, or another territorial newspaper, mentioned them. He shared the finger with the public while it stayed in his possession, about seven weeks.

The Finger Donor

The L.W. Hale in the article is Lower (pronounced Lauer) William Hale. He had moved his family into east Las Vegas, in late 1879 or early 1880, where he partnered up with merchant Joseph Overhuls. By 1881, Hale went out on his own and renewed his craft as a peddler, swinging through the Socorro, Capitan and Fort Sumner regions, before heading back to the Farmington area where his son and family were living.

Descendants say he remained an active peddler years after he relocated permanently along the Ruidoso in late 1883. “Lower was so good, he could have sold ice and snow and a freezer to boot to an Eskimo with the Eskimo walking away smiling ’cause he got a smokin’ good deal,” says Caroline Hale Jones Thomas, a descendant living in Kirkland, Arizona.

Family stories do not tie Hale to Billy the Kid or a finger in a jar. Descendants believe that, given the chance to obtain the Kid’s finger, Hale would have purchased or bartered for it. They also note his generosity, commenting it was reasonable to believe that Hale would send a unique present to a friend, such as the Optic editor.

Sheriff Garrett Returns to Las Vegas

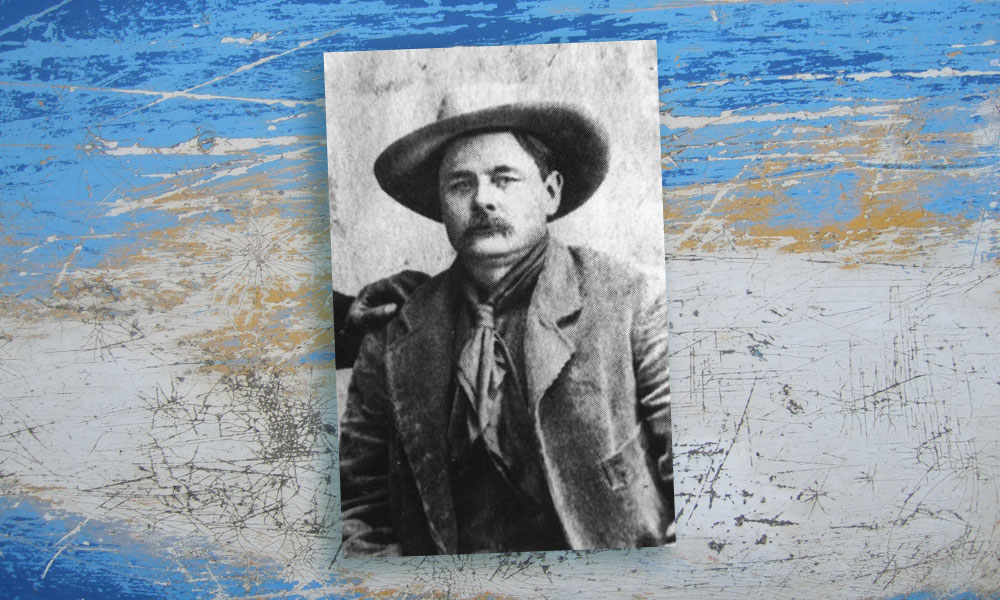

On July 29, Garrett arrived in Las Vegas after a frustrating eight days in Santa Fe, ending with the refusal of acting Territorial Gov. W.G. Ritch to pay Garrett the $500 reward money advertised in May by outgoing Gov. Lew Wallace. The townspeople welcomed and congratulated Garrett; before the sheriff left for his home in Roswell, they gave him more than $1,000 to express their gratitude.

Sometime during his stay, Garrett crossed paths with Kistler, probably stopping by the Optic office near the depot. He most likely saw the finger in the jar, yet no statement was ever printed of his reactions to or opinions of the finger. Given his quiet demeanor and desire to distance himself from the Kid, he likely had nothing to say.

Who Removed the Finger?

As late as 1915, people speculated that Garrett, Deputy Sheriffs Thomas C. “Kip” McKinney and John Poe, either together or one of them alone, had removed the Kid’s trigger finger after his death as a trophy. If true, then one of them must have peddled the trigger finger to Hale, who in turn sent it to the Optic. Or, to be more discrete, one of these men might have sent the finger to the Optic and picked out Hale’s name as the reported donor to ensure no one knew who had actually sent it. However, Poe’s handwritten account, which he began in 1915, refutes this rumor, stating:

There have been many wild and untrue stories of this affair, . . . Another was that we cut off fingers and carried them away as trophies or souvenirs, . . . The story that we had cut off and carried away his fingers was even more absurd, as the thought of such a thing never entered our minds, and besides, we were not that kind of people.

Within two days after the Kid’s funeral, Garrett and a party of Fort Sumner residents had headed northwest via Puerto de Luna, Anton Chico and Las Vegas for Santa Fe. Several men, including postmaster Mike Cosgrove, accompanied Garrett to Las Vegas. Poe and McKinney headed south to Roswell, where McKinney remained and Poe continued on to White Oaks via Lincoln. If Garrett, McKinney or Poe had removed the finger, they could have encountered Hale in their travels. All arrived at their destinations before or on July 19, while the finger was first displayed at the Optic office on July 25.

The Optic’s Finger Leaves New Mexico

Late in 1880, 22-year-old, Swiss-born Albert Kunz left his brother, William, in charge of his drugstore in Waterville, Kansas, and boarded a west-bound train to set up a business in Las Vegas, New Mexico, with Waterville’s former postmaster Charles H. Phillips. In January 1881, Phillips and Kunz opened their drugstore, which was within walking distance of the two-year-old Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad depot. Over the next seven months, the two men and their store became well liked by locals. The Gazette and Optic mentioned the men and their store in favorable terms.

In late summer 1881, Kunz sold his share of the business to Phillips. He had decided he could make a bundle of money by exhibiting the Kid’s finger at local, county and state fairs in Kansas and throughout the Midwest. He paid Kistler $150 for the finger. We don’t know the story behind the deal, yet Kistler might have agreed to sell Kunz the finger on the encouragement of his reverend father, who presided over the Methodist church in Waterville that Kunz had attended.

On the September 8 evening Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe train, Kunz left Las Vegas, carrying the Kid’s finger eastward to Waterville. Being the clever wordsmith that he was, Kistler could not let the departure of the finger go unannounced. He disguised the story in the next afternoon’s Optic, reporting: “Al. Kunz, the druggist, left last night for Waterville, Kansas, taking with him the rarest curiosity that any man ever carried out of the country.”

After Kunz’s arrival in Waterville on September 12, the weekly Waterville Telegraph announced on September 16: “Mr. Albert Kunz returned home last Monday from Las Vegas. He is looking hale and hearty, and brought as a relic of barbarism a specimen of the physical existence of ‘Billy the Kid.’”

Coincidentally, on September 16, Pueblo’s Colorado Daily Chieftain belatedly reacted to the Optic story of July 25: “The editor of the Las Vegas Optic has received from a friend the index finger of ‘Billy the Kid.’ With this particular digit the desperado sent many a man to eternity by the pistol route. The ghastly trophy is preserved in alcohol, and is on exhibition in the Optic office.”

The Optic Keeps the Finger Story Alive

Even though the finger had left town, the Optic still ran with the finger story. This time, City Editor Lute Wilcox took charge, putting this item in the September 19 edition, under the headline “A Desperado’s Darling,” supposedly in response to a letter to the editor:

Billy the Kid, had a sweetheart, so we have just learned. The young lady’s name is Kate Tenney and she lives on Fifteenth street in Oakland, California. She read in the newspapers that the Optic had the index finger of the Kid in pickle, and she has written for it, with a request to send also a photograph of the young killer. We have written Miss Tenney a sorrowful epistle, full of touching condolence and broke the news gently that we had just sold our relic of her lover for $150 cash, and that “Billy” was such a contrary fellow that he wouldn’t sit still long enough for a photographer to get his camera turned loose upon him, hence the photograph she craved must ever be forthcoming. We will see that physician who was fortunate enough to secure Billy’s “stiff” and will present a request for some part of the Kid’s skeleton—a shank bone, or something of that kind, which we will send to the broken-hearted maiden as a lasting memento of her dead lover’s former greatness.

Unfortunately, the Optic never printed the alleged letter. After an investigation, the Optic people supposedly discovered no one in Oakland lived by the name Kate Tenney. Perhaps Wilcox had invented the letter as a gimmick to report the selling price of the finger and to reveal it was no longer in the possession of the office?

Maybe not. Because the next day, September 20, the Optic reprinted the Waterville Telegraph story announcing Kunz’s arrival. Wilcox likely inserted this item to inform locals of the finger’s new owner and whereabouts.

On September 22, the Little Globe in Atchison, Kansas, published a comment on the Optic letter: “Billy the Kid, had a sweetheart. Her name is Kate Teeny [sic], and she lives in Oakland, California. She recently wrote the editor of the Las Vegas Optic requesting him to send the index finger of the Kid which he was reported to have in pickle. She also requested him to send a picture of the young desperado. So says the Optic, which evidently believes the letter genuine. We believe it a scheme of the Optic’s low-born contemporary to get hold of that finger. The Las Vegas Gazette doubtless has a confederate in Oakland, sent there especially to get hold of that finger which has given the Optic such a big boom, both in subscriptions and advertising. It is said that the Optic can not be induced to show the finger to any one who does not put up a year’s subscription in advance.”

The above confirms that the Optic had been successful in using the finger as a gimmick to entice people to purchase a one-year subscription to the paper. Who would not fork out $3.00 for a year’s subscription to the highly-regarded Optic for an opportunity to gawk at the one and only trigger finger of Billy the Kid? As the subscription money came in, so did the advertising dollars. Due to the finger gimmick and other factors, by the end of fall 1881, the Optic had the largest paid circulation of any newspaper in New Mexico—quite an accomplishment for a paper that opened for business in the summer of 1879.

The Optic’s comment of October 14, 1881, ended its contemporaneous news about this finger: “At last accounts the Optic’s preserved finger of Billy the Kid, ‘the mysterious member,’ as Sergeant Hardy would call it, was in Indiana on exhibition at the county fairs. The Optic generally has a finger in every pie that’s going.”

Only a handful of the hundreds of editors across the country who received wire reports from the Optic picked up on the paper’s reports that the Kid’s “digit” either was at the Optic office or had been sold and taken out of New Mexico. This lack of coverage on this and other Kid-related stories reveals that the Kid was of no or little interest to readers across the territory, much less the nation. Except for the few Kid stories in the two months after his death, Kid stories would, until 1925, be almost exclusively told in dime novels. Indeed, nearly all mentions of the Kid over the 43 years after 1881 were in stories of the life and activities of Garrett, when papers credited him as Billy the Kid’s killer.

Kunz’s “Fatal Finger” Disappears

What became of the finger Kunz took from Las Vegas? The finger is not mentioned in later Kansas or Midwest newspapers. Surely something as sensational as the Kid’s finger, if it was exhibited at all, would have attracted pre-fair or during-the-fair coverage by at least one newspaper.

Perhaps Kunz got sidetracked with other business activities and never got around to displaying it at a fair. Perhaps the jar was not labeled and was tossed out. Or perhaps the finger had gotten damaged, and Kunz discarded it. Stranger things have happened. By century’s end, Kunz, then married, left Kansas. In effect, after September 1881, the finger disappeared from history.

Was Billy’s “Fatal Finger” a Fraud?

Almost 10 years after the “fatal finger” story appeared, the Optic printed the following letter on March 13, 1891, under the headline “Those Bones Being Fetched In:”

Puerto De Luna, N.M., March 11th, 1891.—Never fool a professional man, because, being a humbug himself, he never forgives being humbugged. If any one ever said this before, I don’t know it but it goes without saying.

I admit participation in the “Billy the Kid” finger fraud, but the scheme originated in the fertile brain of our now worthy county clerk. The editor of the Optic remarked that he would get even, but he is away off on the bones.

Seeing is believing, so I, to-day, send the bones up by Mr. A.G. Mills for the Optic’s own sight, and I trust the unbelieving Russ and the learned Doctor will see that there is no fraud. The natives say that these are bones of the Jigante, or as they understand it, what we call Centaurs. Traditions and legends they have of this half-man, half-horse and at some future time I will give the Optic’s editors the outlines, and they can write them up.

Now—yes, now, Mr. Editor, when you see the bones, just tell us what animal they belong to!

The letter had been written by Frank N. Page, a businessman from Anton Chico and nearby Puerto de Luna, major villages south of Las Vegas on the most-direct and -traveled road linking Las Vegas to Fort Sumner. The Kid had spent many a day in both communities. As later issues of the Optic revealed, in the weeks before sending this letter, Page and his friends had announced their discovery of the “lower extremities of the tibia, or main bone in the leg, of a calf belonging to the mammoth family, an extinct species of elephant.” Page is admitting he got caught by Kistler in an attempted finger fraud to ensure that Kistler did not “get even” by misreporting these authenticated mammoth bones as fraudulent.

On the surface, Page’s letter pounds all the nails into the coffin lid on the”fatal finger” story. For most, Page’s letter reveals the truth, discloses a hoax and ends the story. For some, the letter only acknowledges that Kistler and the Optic staff had been taken in by a Kid finger hoax. The letter does not disclose the date that bogus finger was sent, whose finger was sent nor when, where and how Page had come to possess a finger to send to the Optic.

None of the Kid historians note Page’s letter as evidence of Kistler being duped. Doing so would discredit any Optic coverage on the Kid. They reject the “fatal finger” story for quite another reason.

Kid historians largely discredit the existence of the Kid’s trigger finger in a jar because this story fits their conception of Kistler as a man who routinely made up sensational stories solely to sell his newspaper. Some have posited that even if the Optic had a finger in a mason jar, it certainly was not the Kid’s.

What these individuals need is a different view of Kistler and the Optic.

Epilogue

Was the “fatal finger” in the Optic office the Kid’s or someone else’s that had been “donated” for an elaborate hoax?

The most compelling evidence that the “fatal finger” is a credible story is the total lack of a single report, interview, letter to the editor or editorial comment in the Gazette and other competitors refuting even one detail in this Optic story.

In a town with such fierce rivalries between newspapers, as in Las Vegas in 1881, the rival newspaper would openly comment about, if not correct, an inaccurate or distorted story. This was the paper’s way of knocking down its rival a few notches and perhaps win back subscribers and advertisers.

The Gazette’s absolute silence on the finger affair is deafening. Over the previous 18 months, the paper had lost its prestige, popularity and a large number of its subscribers to the Optic. The “fatal finger” episode presented the Gazette an excellent opportunity to shift public sentiment and subscribers back to its daily and weekly papers. That the Optic office had displayed the finger and, within days, used it to solicit pay-in-advance, year-long subscriptions to the Optic should have invoked a major reaction by the Gazette.

John H. Koogler, the Gazette’s owner and editor, would have directed his reporters to pursue the story behind that finger, whose it was and how Hale had gotten it. The Gazette staff knew where to find Hale to interview him, yet nobody did. (Hale died near Oscura in June 1908, four months after Garrett had been murdered outside Las Cruces on February 29.) Each day the Gazette failed to refute Kistler’s story was a day the paper lost more readers, subscribers and advertisers to the Optic. Over the next five years, until it went out of business, the Gazette never published an item challenging the authenticity of the finger.

Rival newspapers in the territory were equally silent on this matter. New Mexico newspapers in the 1880s featured numerous examples of editors openly criticizing other papers, including the Optic and Gazette, for printing wrong details, for being taken in a joke or hoax, for sensationalizing a nonevent or for taking a particular position in a story. By not refuting the Optic’s account, all editors in the territory—especially the Gazette’s Kooglers—were saying the Optic had Billy the Kid’s trigger finger.

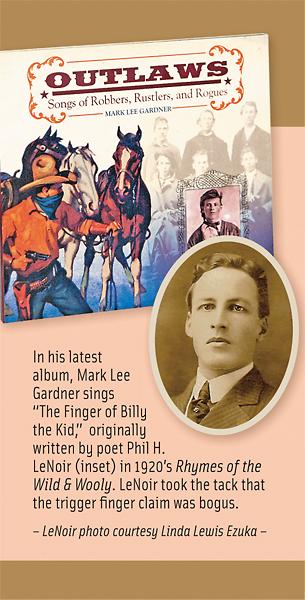

Robert J. Stahl was inspired to research this history after hearing that his father, during a summer 1930s trip, had seen Billy the Kid’s trigger finger in a jar at a barbershop. Now retired in Chandler, Arizona, Stahl is a professor emeritus at Arizona State University and a past president of the National Council for the Social Studies.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Brian Lebel’s Denver Old West Auction –

– Courtesy Marcus Gottschalk –

– Courtesy Ray John de Aragon, Albuquerque, NM –

– Courtesy Caroline Hale Jones Thomas, Kirkland, AZ –