The Old Military Post Road that stretches from Minnesota to Louisiana was the first north-south highway to be built by the United States in the West.

The Old Military Post Road that stretches from Minnesota to Louisiana was the first north-south highway to be built by the United States in the West.

By the mid 1830s, it had become apparent that the frontier demanded mobile troops to separate the White settlements from the Indian tribes as well as to protect the tribes from each other.

On July 2, 1836, President Andrew Jackson signed a bill providing for the defense of the Western frontier. By September, a proposal to build a 1,000-mile military road became law. The road ran along the frontier within the Indian nations, and the government established military posts from Fort Snelling in Minnesota to Fort Jesup in Louisiana.

After the War of 1812, the U.S. had established a string of Indian agencies and forts to preserve peace among the Indians. Fort Snelling, overlooking the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, was completed in 1825. After the passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Fort Snelling became a hub of activity on the upper Mississippi and played an important role in easing tensions between the Ojibwas and White settlers.

Following the Path of Dragoons

I begin my journey at Fort Snelling, where costumed guides greet me and share stories about events at the fort during the 1800s. From Fort Snelling, I follow the path that dragoons and army supply wagons once took by traveling on Highway 52 to Highway 139 in Iowa. I’m making my way to Fort Atkinson—another important fort on the Old Military Post Road.

Fort Atkinson is located in the heart of the lands the government had set aside for the Sioux and Sac nations. A series of treaties established a 40-mile strip of land called “Neutral Ground” between the two tribes. Overlooking Turkey River, Fort Atkinson had been built to protect the Winnebagos, who the army had persuaded to leave their homes in Wisconsin and settle among their old enemies on this neutral ground. In the end, the Winnebagos were moved to lands in northern Minnesota.

Today, Fort Atkinson is one of only 14 properties in Iowa designated by the White House Millennium Council and National Trust for the preservation of our national treasures in the “Save America” program.

Next up is Fort Des Moines, established in 1843, so I travel southwest on I-35. At the confluence of the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers in Iowa, the fort protected the Sac tribe from their enemy, the Sioux. During the summer of 1835, dragoons under Lt. Col. Stephen Kearny, Capt. Nathan Boone and Lt. Albert Lea (the topographer) led an exploratory expedition northward into the Des Moines River Valley. Leading up to what would later become Fort Boone and Fort Dodge, the route is marked today by dragoon trace markers posted through parks and farms. These markers are not on the Old Military Post Road, which leads southward out of Fort Des Moines.

Onward to Homes in Kansas

In 1845, Keokuk was the first of the Sac tribe to lead his people out of Fort Des Moines down the Dragoon Trace to Fort Leavenworth on the Missouri River. The next year, the remainder of the Sacs left their homeland in Iowa and traveled down the military road into Missouri and onward to permanent homes in Kansas.

To follow their route into Missouri, take U.S. 169 and County Road J20 to Ellston, Iowa. The old trail picks up along the Grand River as it enters Missouri, following a southwest diagonal line leading to the Missouri River crossing at Fort Leavenworth, which was the final destination of many nations seeking a permanent home in the West.

Fort Leavenworth, the oldest fort continuously occupied west of the Mississippi, was constructed in 1827 to protect wagon trains heading West. Stop by the Frontier Army Museum and the Buffalo Soldiers Monument at the post before driving south to Highway 5 (Muncie Road), which was also the route of the Santa Fe traders.

Follow Highway 5 to the Kansas River, where Moses Grinter operated his ferry as early as 1831. He charged 50 cents per person and $2.00 for a wagon to cross the river. When the last of the Indian Trade and Intercourse Acts forbade the settlement of Whites in Indian Territory, Grinter married the half-Delaware daughter of Indian trader William Marshall. The Kansas State Historical Society operates the home of the Grinters, near Kansas City. From Grinter’s Ferry, the Military Post Road picks up at

I-435. At Highway 69, the Santa Fe Trail heads west while the Military Post Road turns east toward the border of Missouri.

To leave Kansas City, drive south on U.S. Highway 69. The most significant stretch of the old road can be found by leaving U.S. 69 at the 359 Street exit and traveling east for a few miles to Coldwater Road. Here, in what was the Miami Indian Nation, the countryside remains virtually untouched except for farm homes and fences. Thousands of emigrants and soldiers once found a cool respite in the spring-fed oasis of Coldwater Grove just off 303 Street.

Farther on a few miles, the Military Post Road enters Missouri briefly in the town of West Point, the site of the last trading post before emigrants headed back into Indian Territory. The proslavery town, located on a bluff overlooking Amsterdam, once boasted several fine hotels, many businesses and a school for 300 students. Nothing remains today except the old cemetery. The town was destroyed during the Civil War when Bates County became “The Burnt District” by the passage of Order Number 11, which ordered residents of several Missouri counties to leave the region.

Turn southward on Highway 69 toward Trading Post, where French traders Philip Chouteau and Michel Giraud established a post to trade for furs with the Osage Indians. Turn left at Highway 52 to visit the Marais des Cygnes Massacre site, where Charles Hamelton and his proslavery men dragged 11 Free Staters from their beds to a ravine and shot them. Here, too, was Camp Snyder, once a rendezvous for Home Guards patrolling the border during the Civil War and for John Brown who also visited here.

Return to Highway 69, where you’ll find the Trading Post Museum, with its replica of a log fort built in 1842 by Gen. Winfield Scott to house a company of dragoons who served until after the Civil War ended. It recalls the border war and the skirmish fought here during the war. Near here, the mounted dragoons crossed the Marais des Cygnes, the first major river crossing after leaving the Kansas River.

Stay on Highway 69 and drive southward toward Pleasanton. Two miles south of town, turn on Highway 31, toward Mound City, to visit the site of the Battle of Mine Creek—the largest mounted cavalry battle of the Civil War and the last battle fought in the West. Vastly outnumbered Union men defeated the forces of Confederate Gen. Sterling Price here, when his 500 baggage wagons, loaded with loot from the Battle of Westport and other battles in Missouri, lodged in the stream’s crossing.

Head back to Highway 69 and drive southward through rolling hills of prairie land. Fort Scott lies ahead. Kearny and Boone wanted to relocate Fort Washington to a Spring River site near present-day Baxter Springs. The Cherokee who owned the land demanded the unheard of price of $1,000 an acre for the post to be built on his land, so they chose to move northward to land that had been set aside for the New York tribes. They selected a site on the Marmaton River for Fort Scott, founded in 1842 and named for Union Gen. Winfield Scott.

During its short life as a frontier military post, Fort Scott saw turbulent times. First sent out to make peace between the Indians and White settlers in Missouri, the dragoons found themselves in a border war between Free Staters and Missourians. Part of the dragoons served with Zachary Taylor at Buena Vista during the Mexican War. In 1844, dragoons from Forts Leavenworth and Scott rode into the Plains to restore order among the Pawnees and Sioux.

Continuing to hug Missouri, the road runs along the state line south of Fort Scott and onward to Pittsburg. At Baxter Springs, “First Cowtown in Kansas,” the military section of this road is called “Black Dog Trail.”

Next Stop: Oklahoma

Fort Gibson, the next fort on the Military Post Road, was established near the Arkansas River and located in the Cherokee Nation. As Oklahoma’s oldest fort, it was instrumental in bringing a peaceful settlement to the southeastern nations who had signed the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830.

The route to Fort Gibson follows Highways 59 to 10 until it reaches Tahlequah, Oklahoma. From Tahlequah, head south on 10 to Fort Gibson, just east of Muskogee. At the forks of the Verdigris, Arkansas and Neosho Rivers sits Fort Gibson, where the infamous Trail of Tears ended and the Cherokees found a permanent home in the West.

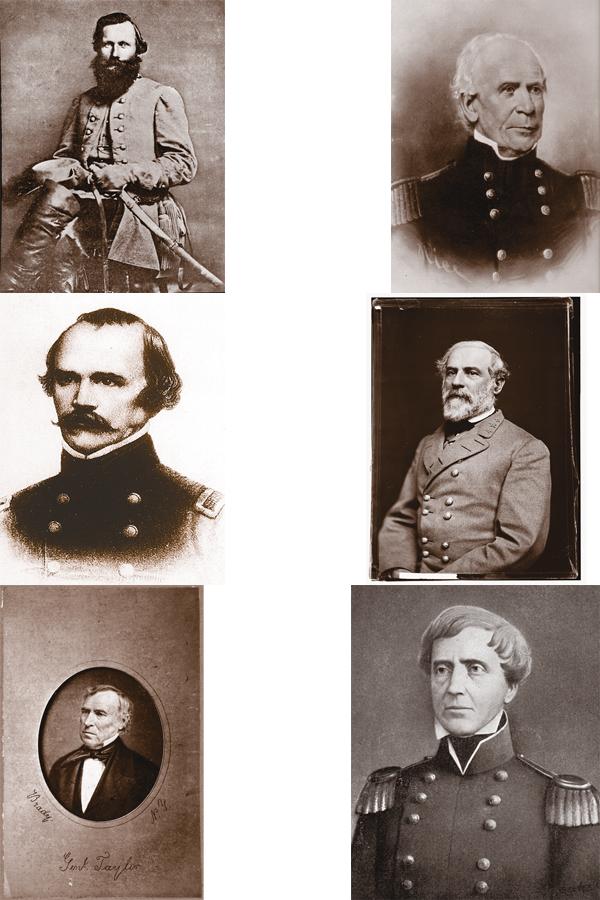

Many graduates from West Point were sent out to Fort Gibson to get their first taste of army life and frontier experience. Among those who served at the post were: Zachary Taylor, Thomas Jesup, Stephen Kearny, Albert Sidney Johnston, J.E.B. Stuart and Robert E. Lee. The army abandoned the fort in 1890, and the government returned the land to the Cherokees while Oklahoma was still designated as Indian Territory. Traces of the Military Post Road are found in Stigler and Talihina.

From Fort Gibson, you can reach Fort Towson by taking Route 82 to Highway 271 and then I-70. Fort Towson is situated in southeastern Oklahoma, just above the Red River, and passes through the heart of the Choctaw Nation.

Because of the threat of war with Mexico in the 1840s, the military road in Fort Towson became an important link for aiding settlers going into Texas and for supplying the army. When hostilities with Mexico ended, the fort was abandoned in 1856; however, during the Civil War, it served as a Confederate command post. The Oklahoma Historical Society preserves the Fort Towson site.

No Man’s Territory

The last important fort on the Military Post Road is located at Fort Jesup in Louisiana. Prior to the construction of the road, the north-south travel in the Fort Jesup area was by water routes. With the construction of Military Road Number 11, Fort Jesup became the main north-south artery in the region.

Leave Oklahoma on Highways 70 to 71 and drive to U.S. 371 to reach Washington, Arkansas. Drive south to Haynesville, Louisiana, and continue south until the highway crosses Interstate 20 in Minden (at the intersection of the Military Post and Wire Roads). Travel State Road 792 to Ringgold where an old section of the road on Highway 371 can be traveled within the city limits. You are still on the route of the Military Post Road as you continue southward to Coushatta. Follow the road to Campti, Grand Ecore and Natchitoches. The site of Fort Jesup lies a short distance off State Road 117 on Highway 6, about 45 miles south of Ringgold.

Since the Louisiana Purchase Treaty of 1803 never clearly defined the western boundary of Louisiana, this section was once part of “No Man’s Territory.” But the boundary became fixed in the Florida Purchase Treaty of 1819; three years later, the government built Fort Jesup. Zachary Taylor commanded the garrison and established law and order in the territory. In 1845, half of the army traveled through the fort, heading to war with Mexico. The following year, the fort was abandoned.

In some places on the wide open prairies where you’ll find yourself traveling through, the Old Military Post Road spans an area a mile wide. Surveyed and laid out by the U.S. Army, the continuous 1,000-mile road remains a wonderful piece of history.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –