America was exploding in the mid-1800s.

America was exploding in the mid-1800s.

From coast to coast, it was a time of great anxiety—the Civil War was looming, the Mexican War was waging, the Mormon War was simmering, gold was discovered in the hills of California and Colorado—and yet one of the most popular memories of those days is 80 skinny boys and their fast ponies.

The Pony Express is an icon of the Old West. It epitomized the “can-do” spirit that is part of the American gene pool; it fed the hunger for heroic endurance; it tickled the fancy of facing danger with derring-do and it spawned myths that will probably never die.

But if you were asked how long the Pony Express was the major mail carrier across the United States—19 years, 19 months, 19 days—you’d probably get it wrong.

The epithet for one of the most thrilling and colorful moments of Western history is this: April 3, 1860 to October 26, 1861. Almost 19 months. From the first pony to race out of St. Joseph, Missouri, to the last pony to reach Sacramento, California—a mere 18 months, 23 days.

When the Pony Express ended, its riders had covered over 600,000 miles; service had been interrupted only once and only one packet of mail was ever lost. Through heat and cold, dust and snow, blizzard and drought, the young boys on their fast ponies kept a divided nation informed and in touch at a moment of great anxiety. Some say the Pony Express helped save the Union.

And just think: Every mile was covered at a full gallop.

Tom West called them “Heroes on Horseback” in his 1969 history of the Pony Express.

“Nothing stopped these daring riders, the mail had to go through,” West wrote. “Sometimes a rider limped in with an arrow protruding from his back, as did one Mexican. Others collapsed over their ponies’ withers, drilled by a renegade bullet, as did Bob Walker. Yet their code was inflexible: the mail came first, the horse second, the rider last.”

The most spectacular example of all had to be Bob Haslam, who once rode 370 miles in 36 hours—a feat spectacular enough on its own, since the U.S. Cavalry in those days rarely covered more than 50 miles in a day. Yet Haslam made his incredible journey while pursued by Indians and suffering from two bullet wounds. The first had pierced his gun-arm, leaving it useless. The second had ripped through his cheek, knocking out a row of teeth and smashing his jawbone. Yet, nearly half-dead and badly crippled, he refused to stop riding. “The Express Company awarded Haslam $100 in recognition of his feat,” West wrote. “Bob thought it was nothing to get fussed up about. He was a Pony Express rider. Wasn’t it his job?”

The job was actually pretty simple: Get on the fastest horse money could buy, sit on a specially-designed leather pouch that held the mail—called a mochila, it would stay on the horse even if the rider couldn’t—and gallop at breakneck speed over your portion of an eight-state, 1,966-mile route. Change from one fast pony to another every 12 to 15 miles, to be sure the animals were always at optimum speed. There were only 10 days to cover the entire route, so the mochila had to travel 200 miles a day.

Hundreds of young men answered an ad that promised little but grief: “Wanted. Young, skinny, wiry fellows. Not over 18. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred.”

Again and again and again, these brave boys carried on, from one relay station to the next, until the words inside the pouch—the love letters and notes of sadness and news of the emerging nation—could reach their eager readers.

That’s why there was a Pony Express in the first place—this hunger for news.

Communication was so difficult in those days, the two coasts of the nation could just as well have been on different planets. There were but two ways to get a message from the East Coast to the West: entrust it to someone on a wagon train and hope it eventually reached the intended, or send it on a ship sailing for San Francisco around Cape Horn. Either way, it was a tedious, months-long journey.

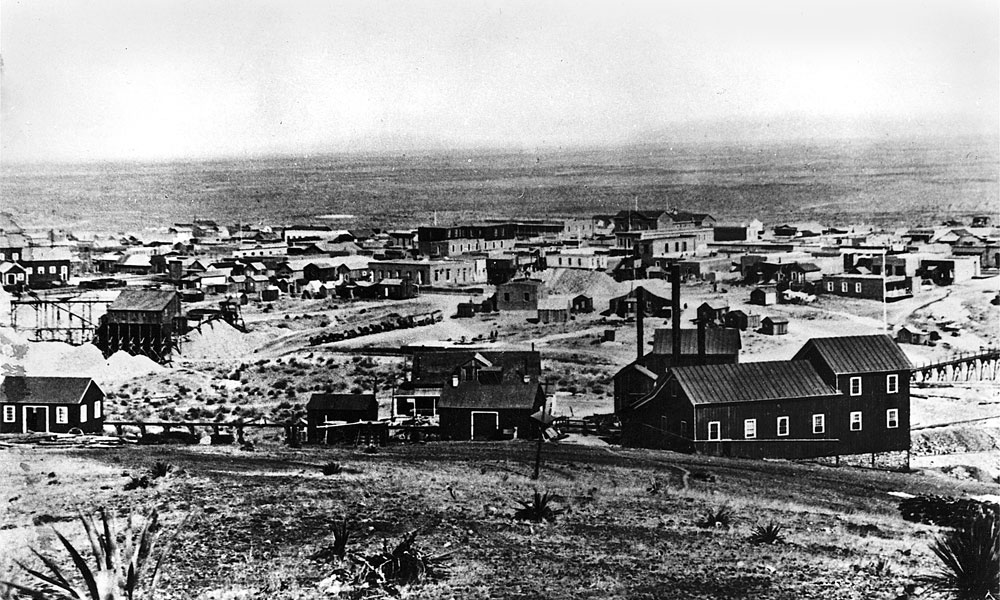

A perfect example of how slow that was is this: news that gold had been discovered in California in 1848 took almost six months to reach the Eastern states. By the time people in New York and Massachusetts were screaming “Gold in California,” many California towns were already ghost towns—long since deserted as people had rushed to Sutter’s Mill, searching for their fortune.

As West noted, “gold fever” was indeed infectious. “Everyone, it seemed, was heading for California,” he wrote. “The gold-crazed hordes came by wagon across the Great Plains, by ship around Cape Horn, by Muleback across the Isthmus of Panama. For two months, a continuous caravan of white-topped wagons, like a gigantic centipede, crept across the plains between Missouri and Fort Laramie.”

California was such a popular destination, within five years it had a half million residents.

“Soon, these adventurers began to crave one thing even more than gold,” West reported. “They wanted news from home. . . . There were no letters or newspapers, and the demand for mail service grew thunderous.”

Congress got a petition from 75,000 Californians demanding mail service. Thousands of women left back East pestered the politicians.

Pressure has always made politicians move and now they moved in a variety of ways: they tried a ship, but no sooner had the first mail vessel anchored in San Francisco Bay than her entire crew deserted for the goldfields. Congress appropriated $30,000 to have camels deliver the mail, but that didn’t work, either. Finally, it seemed clear that the only viable option was an overland route using sturdy stagecoaches.

The first, known as the “Oxbow” and run by John Butterfield, looped through the Southern states. The route was longer than the Northern immigrant route, but it avoided some tortuous mountain passes and the sub-zero winters of the Northern plains. At least, that was the public explanation for why the longer route was financed by the U.S. Government. The real reason was powerful Southern politicians kept most government subsidies on Southwestern trails, and the mail was no exception.

The first Oxbow stage left St. Louis for the West Coast on September 15, 1858. Butterfield promised mail delivery in 25 days.

“But California, now pouring millions in gold into the coffers of the East, was not satisfied,” West noted. “Senator [William] Gwin of California fought hard for a northern route. The Oxbow Route, he declared, was slow, uncertain and wasteful.”

And then, another gold rush incited the nation. “Pike’s Peak or Bust” became the new slogan as people rushed to Colorado. And with them came new complaints about the lack of mail and news. But Senator Gwin’s screams about the need for a Northern route were lost on Southern-leaning President Buchanan and his postmaster general.

As West recounted it, Senator Gwin one day got an unexpected visitor. If he hadn’t known William Russell had one of the biggest freighting outfits in the country, he would have laughed at his guest’s absurd proposition: Russell promised to take mail from East to West in 10 days. When the astonished senator asked how, Russell answered in two words: “fast ponies.”

Russell wanted a government contract; Senator Gwin said Congress would have to be persuaded first; Russell promised to persuade them. At that moment, he was an owner of Russell, Majors and Wadell, which was reputed to own over 6,000 freight wagons and 75,000 freight oxen and employed some 5,000 bullwhackers, blacksmiths and laborers. The company already had government contracts—one to carry mail on its stage line from Kansas to Utah, another to haul freight for the army that was fighting the Mormon Wars in Utah and Wyoming. Russell had to browbeat his partners into fronting the risky new idea, but they eventually agreed.

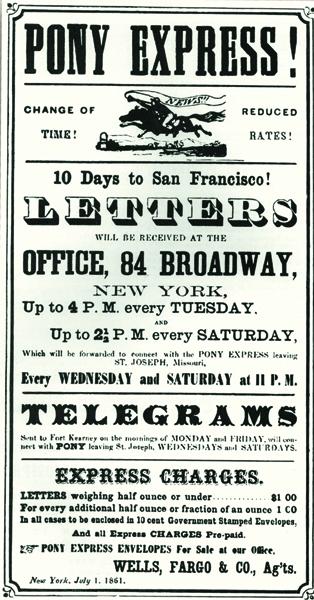

Here’s how they advertised the daring venture: “Mail to be rushed west by racing ponies! Butterfield Stage time cut in half! Ten days from coast to coast!”

“The news spread fast,” West recounted. “It blazed from newspaper headlines. It was discussed around potbellied stoves in frontier stores. It was hailed with joy in isolated mining camps. It stirred half a million settlers in that new empire west of the towering Sierra Nevada Mountains. Everyone assumed that the venture was government backed. But despite Senator Gwin’s fiery oratory, no government subsidy was provided. Congress was caught in the growing tension between North and South. The thorny subject of slavery threatened to split the country. Soon it was to plunge them into bitter conflict. In the event of war, the gold shipped from California would be badly needed by both sides, but the South hoped to drain gold out of California by means of Butterfield’s Southern route. For this reason, Southern congressmen blocked every effort of Northerners to subsidize a mail route across the northern plains.”

Russell and his firm pressed ahead anyway. They built 138 relay stations: “home” stations were 75 miles apart; between them, smaller way stations every 15 to 20 miles held fresh mounts. The mail moved in a gigantic relay race. Riders from both ends would gallop out, change horses, continue galloping, pass the mochila off to a fresh rider after some 75 miles or so, then pick up a new mochila coming from the other direction from another rider and retrace the route.

Russell’s agents bought the best horses money could buy: Kentucky thoroughbreds for the flat prairie; mustangs for the rugged Western terrain. They needed great horses for two reasons: speed and safety. The express riders were alone—they had to be able to outrun bandits and hostile Indians. While saddle horses in 1860 were going for $50, the Pony Express paid from $150 to $200 per mount.

The riders were paid $50 a month and up—good pay in those days. From the hundreds who applied, 80 were chosen—“the pick of the frontier” they were called. All were young men; none weighed more than 125 pounds; all had to sign this oath: “I, do hereby swear, before the Great and Living God, that during my engagement, and while I am an employee of Russell, Majors and Waddell, I will, under no circumstances, use profane language, that I will drink no intoxicating liquors, that I will not quarrel or fight with any other employee of the firm, and that in every respect I will conduct myself honestly, be faithful to my duties and so direct all my acts as to win the confidence of my employers, so help me God.”

The riders were issued bright red shirts and blue pants, although most preferred to wear range gear—a flannel shirt, vest and denim pants tucked into their riding boots. Of course, they wore wide-brimmed hats, and each was given a Colt revolver, along with a bowie knife and lightweight rifle. Many discarded the rifles to save weight. They also were given horns to signal their approach to relay stations, but few ever used them.

Riders 1,966 miles apart—one in Missouri, the other in California—began it all on April 3, 1860. The Westbound mochila arrived in Sacramento at 5:30 p.m. April 13, almost two hours early to meet the 10-day boast. It contained tissue-printed newspapers, 49 letters, five telegrams and congratulations from President Buchanan.

“William Russell and his daredevil riders had made good,” West noted. “But the critics said, ‘A publicity stunt. Bill Russell can’t keep it up.’”

But he did. For the next month, the Pony Express made good on its promise of 10-day service. And then everything stopped. A Paiute uprising destroyed scores of express stations, and for a couple of months, everything came to a halt. When the uprising was quelled, service-as-promised began again.

Perhaps the single most significant achievement of the Pony Express was keeping California in the Union. Historians note the rapid communication the mail service offered kept gold-rich California up to date about the pending Civil War. But California loyalties were still doubtful when Abraham Lincoln was elected president. Californians waited with great anticipation to see what policies the new leader would outline in his inaugural address. Weeks before the inauguration, the Pony Express’ owners made elaborate preparations for speeding Lincoln’s words to California—hiring hundreds of extra men, arranging fresh relay horses every 10 miles. The planning resulted in the fastest trip ever made by the Pony Express, just seven days and 17 hours.

Californians must have liked what the president said. They also could have been swayed by the early Union victories they were reading about in newspapers rushed to them on horseback. The state and its gold stayed in the Union.

What wouldn’t stay was patience. Ten days instead of months sounded good in 1860, but instant communication via the telegraph sounded a lot better in 1861.

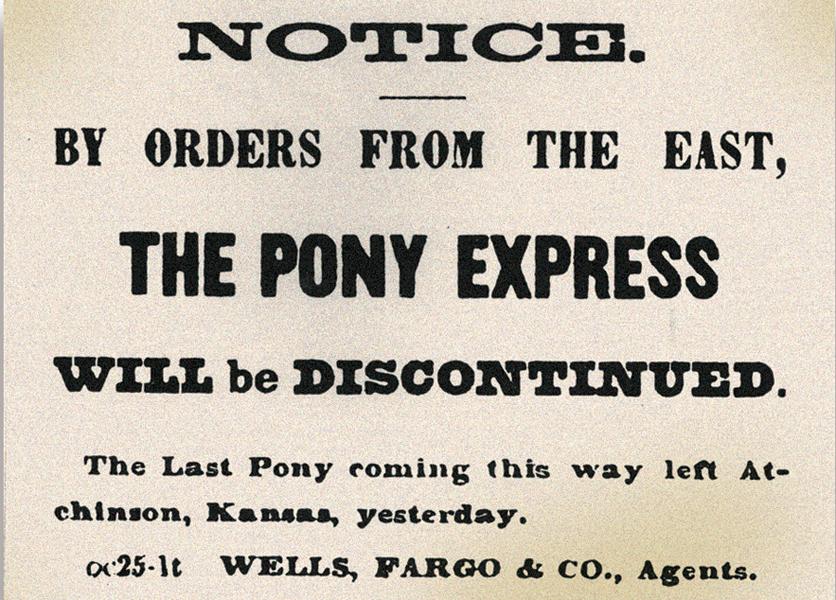

The Eastward construction crew of the transcontinental telegraph project arrived in Salt Lake City on October 24, 1861. Two days later, the Pony Express ceased operations.

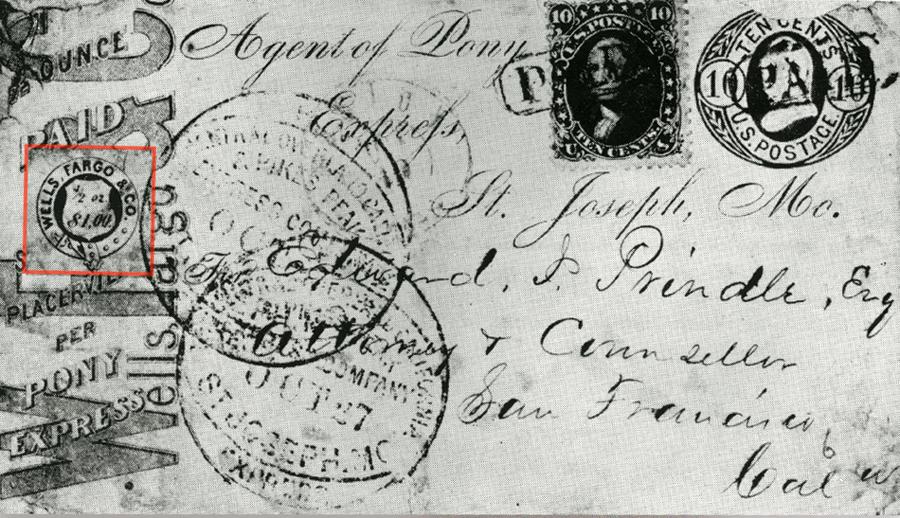

But as grateful as everyone was for all the Pony Express had meant to the nation, Congress still stiffed Russell, Majors and Waddell. The partners had invested some $700,000 in creating the Pony Express, and would leave a $200,000 deficit when it was all over. Their company was sold at auction in 1862 to Ben Holladay, a freight business owner who would branch out into stagecoaches, steamships and railroads. He’d eventually sell it to Wells Fargo for $2 million.

It was a short run, but a run that would forever endear the Pony Express to American hearts.

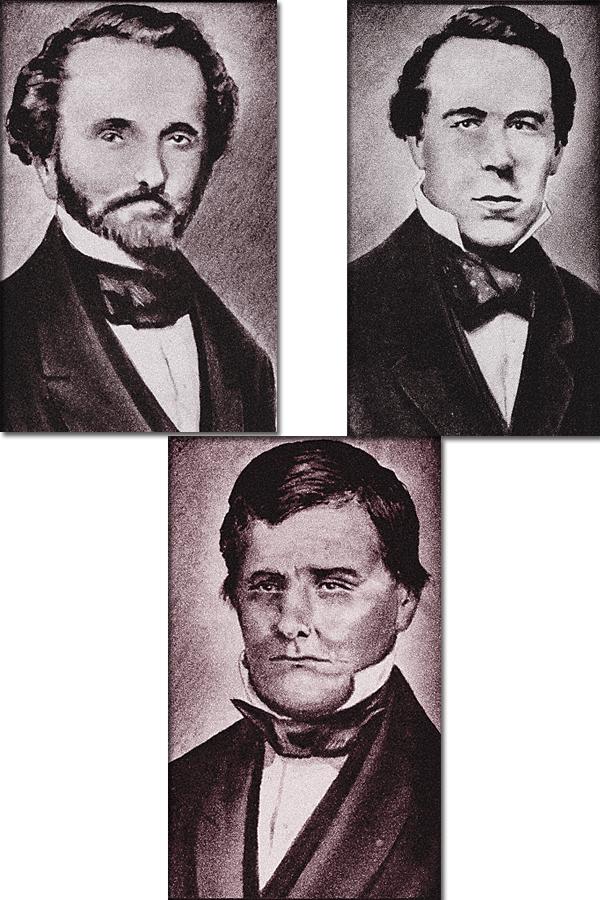

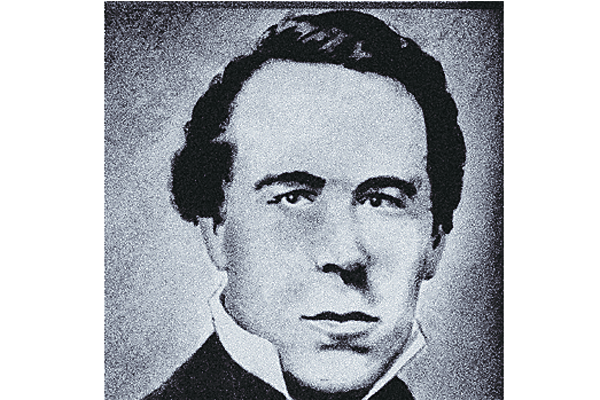

Who Was The First Rider?

No less than seven riders have been named as the lad who saddled up the first Pony Express run from St. Joseph, Missouri, on April 3, 1860.

How can this be, you may wonder, if you think history is neat and tidy and the result of good record keeping. None of that was at work as this new experiment in communication began, and the very things that would make it so valuable—the pending Civil War, the gold strikes in California, the turmoil of a divided nation—are the reasons that records either weren’t kept or were shoddy. There’s also evidence that a fire destroyed the paltry records that were maintained.

So there is no accurate ledger showing the riders’ names, and that leaves us pondering “who was the first?”

According to the St. Joseph Weekly West of April 7, 1860, the first rider was “a Mr. Richardson formerly a sailor, and a man accustomed to every description of hardship. . . .”

A 1907 letter names Alex Carlisle as the first rider out of Missouri.

In 1923, the Daughters of the American Revolution put their faith in the original newspaper account in designating Williamson as the first rider when they placed a monument in Patee Park where the Pony Express Museum now stands. (The decision was so controversial, one former rider refused to attend the ceremony.)

That same year, historian Glen Bradley, who had written a book on the Pony Express, concluded Johnny Fry was the first rider.

A decade later, the St. Joseph Historical Society agreed on Fry, after determining that Billy Richardson was only 10 years old in 1860. They also relied on eyewitnesses, including:

—Fry’s sweetheart at the time, now a Mrs. Lewars, said she waved to Johnny as he rode past on the first ride.

—Two later riders both swore it was Fry.

—Historian and member of a pioneer family, Mary Alicia Owen said, “Why, everyone always knew the first rider out was Johnny Fry.”

But even that didn’t settle the argument.

In his 1959 book Pony Express—the Great Gamble, writer Roy S. Bloss noted there have been seven candidates for first rider, but “by process of literary attrition,” it came down to ‘a draw’ between Johnny Fry and William Richardson.

Tom West, in his 1969 The Story Of The Pony Express:?Heroes on Horseback, didn’t hint at any question in declaring that the Westbound rider was Bill Richardson.

As West told it, Richardson was supposed to ride out of the Patee House in St. Joseph at 5 p.m., but the mail coming in on the train from Washington was delayed. When it did arrive, he was held up even longer with speeches and congratulations—St. Joseph Mayor M. Jeff Thompson gave the inaugural speech, which was fitting since the town provided free office space for the Pony Express.

West wrote that Richardson finally swung into the saddle at 7:15 p.m. and switched mounts three times before his run was up.

But that’s not how the Pony Express Museum in St. Joseph recounts the scene. The museum is so certain the first rider was Johnny Fry, its website address is johnnyfry@ponyexpress.org. The museum says Fry mounted a horse named Sylph and galloped out of town at 7:15 p.m.

For our money, we think the final word should go to someone who knew the truth. And we’ve discovered he spoke out in 1938.

Billy Richardson had been out of St. Joseph for many years and so he had not heard of the controversy. He eventually returned to the town and died there in 1947 at age 96. His obituary stated he told this to his friends:

“A writer billed me as the first Pony Express rider but that’s not so. Johnny Fry was the first rider. It just happened that my brother, Paul Coburn, was the manager for the Pony Express here and he accidentally threw the mail pouch on my pony instead of Fry’s. We set off down the street with the ponies’ hooves clattering and my pony carrying mail. Down at the ferry, however, the mail was transferred to Fry’s mount. He was the one who deserved the credit.”

Court records show Billy Richardson was a ward of Bella Hughes, a co-director of the company that created the Pony Express, and his half brother was indeed Paul Coburn.

So there you go.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

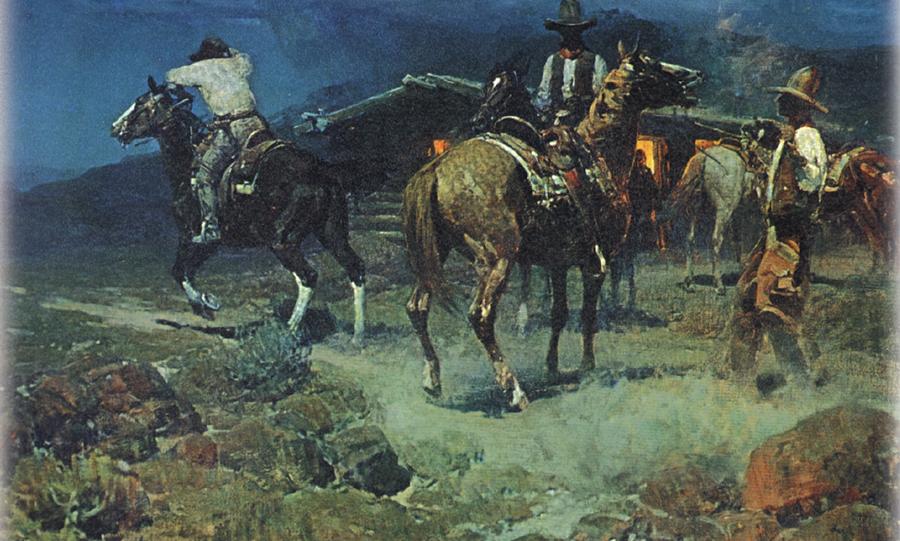

– Painting by Frank Tenney Johnson –

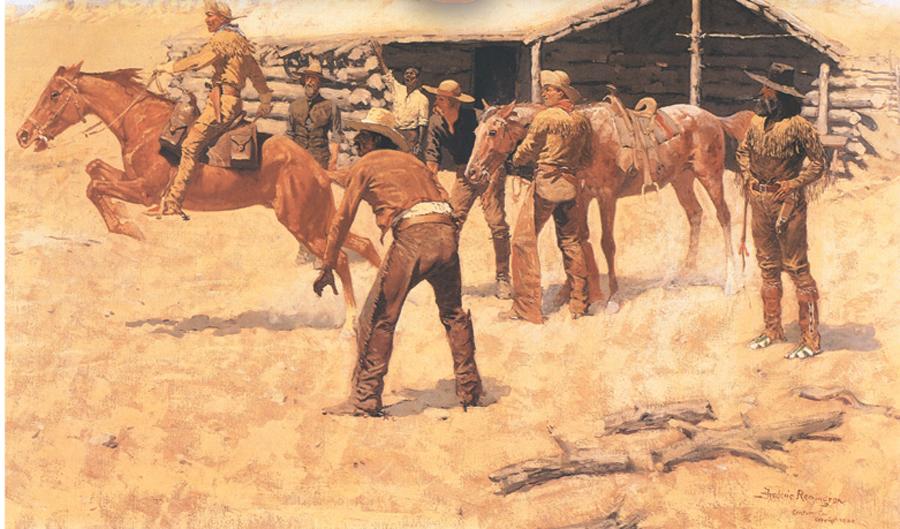

– Painting by Frederic Remington –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –