“Did you sketch this picture of my daughter?” Cindy Costner, Kevin’s wife at the time, asked a Union soldier during a lull in the Dances With Wolves filming in 1989.

“Did you sketch this picture of my daughter?” Cindy Costner, Kevin’s wife at the time, asked a Union soldier during a lull in the Dances With Wolves filming in 1989.

“I did,” answered Jim Hatzell, a Western artist from Rapid City, South Dakota.

“May I see your sketchbook?” asked Cindy, who then began flipping through his sketches and commenting how much she liked his artwork.

Hatzell and I had met as the film crew positioned us for Lt. John J. Dunbar’s hospital escape scene. We later worked together on the Fort Hays and final search for Dunbar sets. Many True West readers know Hatzell’s work; they voted him “Best Living Western Photographer” in 2009.

Hollywood would see him more as a modern-day Joe de Young. A Montana boy who legendary cowboy artist Charlie Russell took under his wing, de Young got hired on a handful of movies, some of the best-looking movies ever. One of them is 1936’s The Plainsman; its plot is nonsense, but the clothes and the guns are right. De Young sketched the costume designs for the main actors. He also sketched the sets for 1953’s Shane, which looked like they came right out of a Russell painting, and he designed the costumes (all fantastic, excepting Shane’s hat, which was supposed to be a Boss of the Plains Stetson, but they put a John Wayne fedora on him).

Hatzell doesn’t shy from this association. “If someone wants to get it right, I’ll bust my butt to get it right,” he admits.I recently visited the artist at his home to discuss his role in Western films.

BM: What helped you gain credibility as a film re-enactor?

JH: All those years of being a film re-enactor, I walked around the sets sketching people, watching the crews and learning. That’s how I started getting the set jobs. I worked on Wyatt Earp as set dresser for the buffalo hide wagon. If you pile 40 buffalo robes in a wagon, it’s going to fill up. But they didn’t have 40 buffalo robes, so we piled straw bales on the wagon and covered them with a layer of buffalo robes.

How did you get involved in Dances With Wolves?

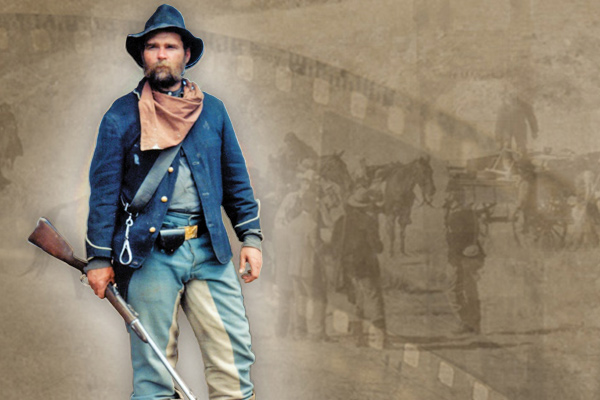

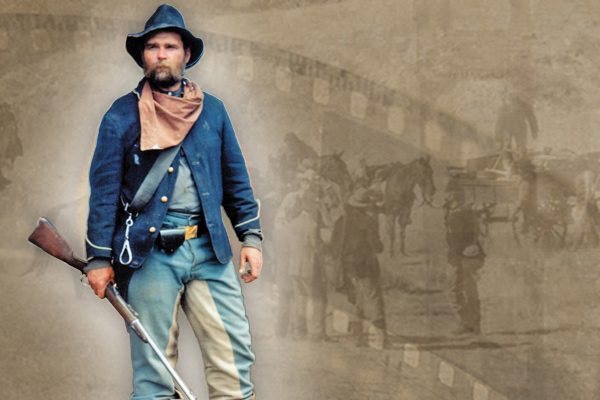

I happened to have a cavalry outfit and sent a photograph of me wearing it to Andy Cannon, the re-enactor coordinator. Cannon then hired me for Dances With Wolves’s opening Civil War scene and kept me on for additional scenes.

What was your take on Kevin Costner?

I thought he could do no wrong. It was a bad first movie to do—it spoiled me. When Costner filmed the Civil War scenes, he was behind schedule and losing money. The critics were saying, “A Western? Nobody goes to Westerns anymore.”

The film crew figured it would be 10 a.m. before they got the re-enactors through wardrobe and makeup and had assistant directors place them. By using Civil War re-enactors, who operated by military discipline and were on set by sunup, Costner was able to make up lost time and save money.

On the Fort Hays set, Costner rides up to the headquarters building and dismounts. He’s thinking, “What do I do now?” because none of this is scripted.

Skip Harrington, a re-enactor, says to Costner, “If an officer rides into a fort, an enlisted man will take his horse.”

Costner says, “That’s great. By the way, how would I salute?” So Skip shows him.

They didn’t have to hire experts because the re-enactors were the experts. I saw this happen in film after film. Re-enactors can act as unofficial technical advisors.

I worked on films where horses were acting up, tossing riders and breaking their bones because they were sore from Indian extras riding them bareback. When I started working as re-enactor coordinator for films and hiring Indians, I asked the film directors if they had any qualms about putting saddles on the horses and covering the saddles with blankets. They said, “As long as we don’t notice that’s fine.” So we filmed the same types of scenes that were just as intense, and we had zero accidents.

What was your favorite experience on a movie set?

Far and Away’s Oklahoma land rush was probably the most amazing scene I got to do in a movie. You know; you were there. When they first blew off the cannon, I didn’t get in the first race because I was with the cavalry, so I got to watch. It was amazing to see the thousand riders and 250 wagons all take off at a gallop!

What are your favorite movies you worked on?

Dances With Wolves. Crazy Horse was a favorite because we did the entire Indian Wars and lived in the saddle.

Are you a stickler for accuracy?

John Wayne got away with using an 1873 Peacemaker in the Comancheros that took place in 1843, but you have to know what works for the period and what won’t. If you’re doing Custer’s “Last Stand,” you have to make everything accurate. If you look at Frederic Remington or Charlie Russell paintings, you see the quivers and bows hang from the Indians’ left sides; that’s because every Indian was right-handed. So during a film, I make the guys wear them correctly.

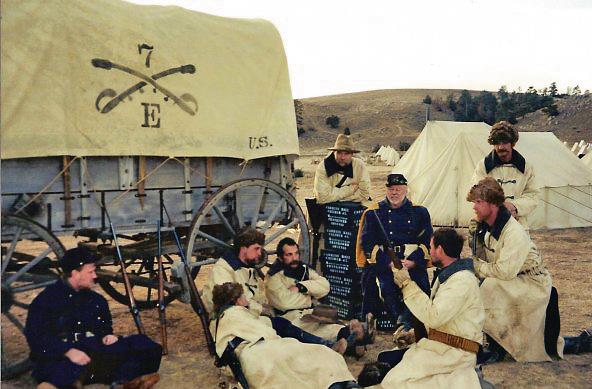

During the BBC film Custer’s Plan, we moved heaven and earth to get the correct colors of horses by company since Custer had insisted one company be sorrels, three companies all bays and Company E all grays. We brought together 20 grays for those shots.

Before I got into the movie business, I was a movie watcher. I hated seeing wrong things. Since I wanted to be a Western artist, I studied old photographs. I could tell what was good and what wasn’t. I studied Charlie Russell and Frederic Remington paintings. I used a magnifying glass to study the details so when I watched a movie and I saw something wrong, that bugged me. On the set, I had a chance to fix it.

What role did you serve for the 2004 film Hidalgo?

I worked as Phil Spangenberger’s assistant on Hidalgo. Phil asked me to make a map of where each military company was when the shooting started at Wounded Knee. I reviewed Rex Alan Smith’s Moon of Popping Trees, one of the best books on Wounded Knee. It took me hours to make the map. Phil liked it, introduced me to the director and said I had this map based on the history.

The director said, “Tell me the microwave version.” So I showed him the map and told him the history of how it happened. He said, “That’s great. Thank you. Wait ’til you see how we do it!”

Besides re-enacting, what else did you do on Rough Riders?

Twenty of us re-enactors were pulled together to train the extras playing the Rough Riders, the 71st New York and the Buffalo Soldiers. Alan Brooks, one of the re-enactors, brought copies of an 1896 military manual. We trained these guys to march, stand at attention, salute—and everything needed for combat scenes.

Which actor have you most enjoyed working with?

Sam Elliott. I worked with him on Gettysburg, Buffalo Girls and Rough Riders. I’ll tell you one Sam Elliott story, and why he is a superb guy. This is on Rough Riders. We’re part of the crew, yet we’re in uniform so we look like extras. We’d be standing in line for lunch and some of the crew would jump in front of us saying, “We’re crew,” and we’d say, “We’re crew too.” And they’d say, “You guys are with the cast.”

They just cut ahead. It took three times as long to get lunch; sometimes we had things we needed to do, so we’d blow off lunch to get the job done. Sam Elliott was watching this, so he jumps in line with us. Nobody cut in front of Sam Elliott.

What’s on the horizon?

Next week, I’m working on an episode of Hoarders.

What’s one of your most cherished film mementos?

A Dances With Wolves photo, inscribed, “Hi Jim, Your friend Harry Carey.” Carey Jr. worked on the John Ford cavalry films. Harry saw my movie photos at a Durango, Colorado, art show and asked questions about re-enactors in the movies. He said, “You’re doing the same thing we did. We were a family. We knew we could count on each other.”

I bought his book A Company of Heroes, and he wrote in it, “Thank you for carrying on the tradition.”

I got to thinking about it; we really do carry on the tradition.

You can spot Bill Markley’s mug in several Western films. Read more about Jim Hatzell and Markley’s exploits in Dances With Wolves in Markley’s book, Dakota Epic: Experiences of a Reenactor During the Filming of Dances With Wolves.

Photo Gallery

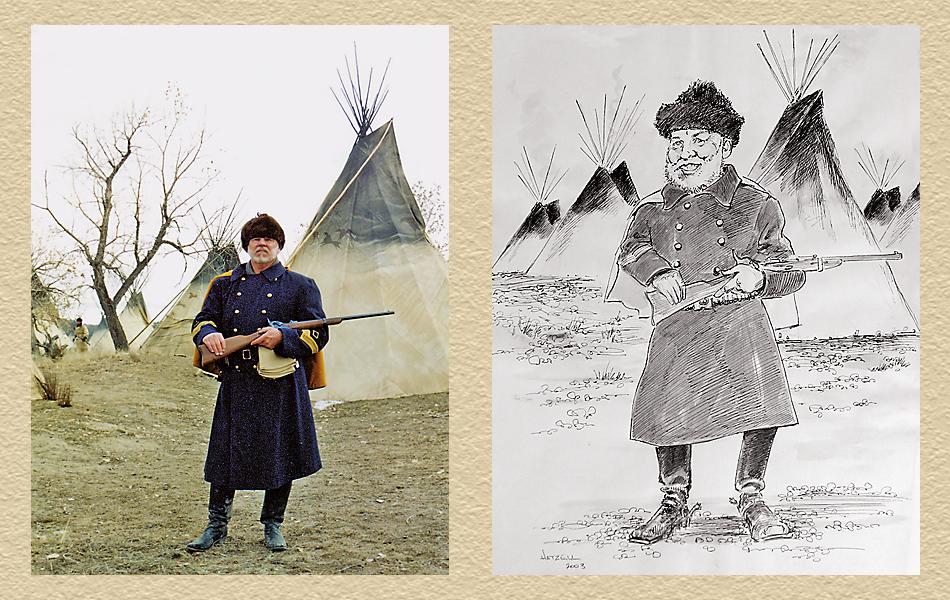

Hatzell on the winter cavalry set of the 1990 film Dances With Wolves.

Hatzell goofing around on the set of ABC’s 1994 miniseries Heaven and Hell, a movie Hatzell admits was the “worst film I’ve ever made (and I worked on Rob Reiner’s North).”

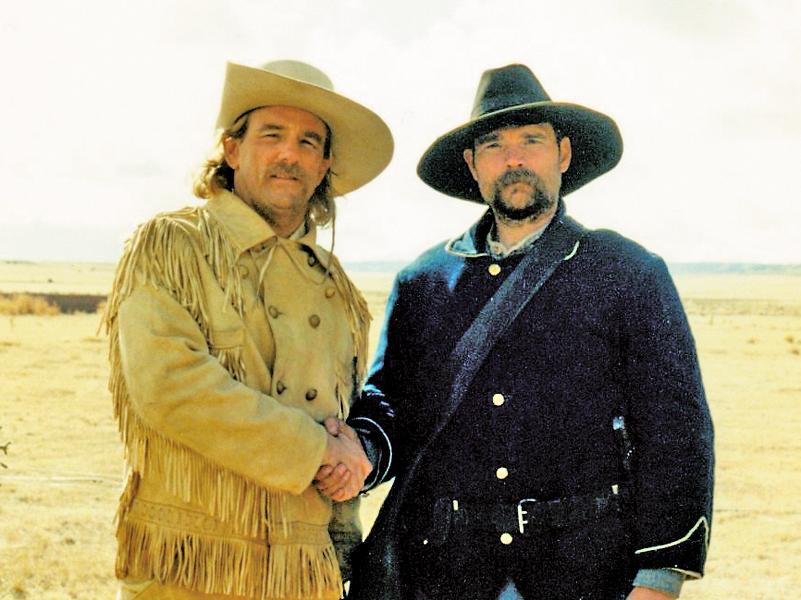

With John Diehl as Custer (at left) in CBS’s 1995 film Buffalo Girls.

Hatzell wears Director Kevin Costner’s hat on the buffalo hunting set of 1994’s Wyatt Earp.

With Phil Spangenberger (in chair) and other cast members in 2004’s Hidalgo.

– Photo By Mark Latza –

With Ron Harris (at right) in TNT’s 1998 film Two for Texas.

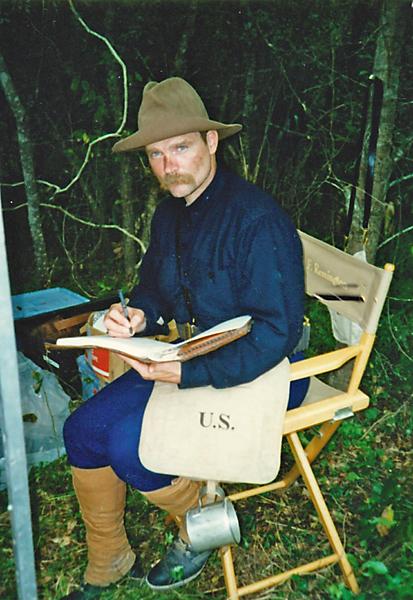

Hatzell on the set of TNT’s 1997 film Rough Riders, sitting in the chair reserved for the actor playing artist Frederic Remington. (Director John Milius had character’s names, instead of actor’s names, printed on set chairs.)

Worked with Sam Elliott (at left) in 1993’s Gettysburg.

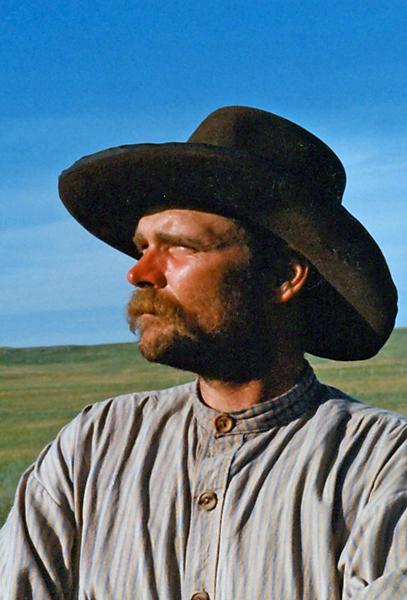

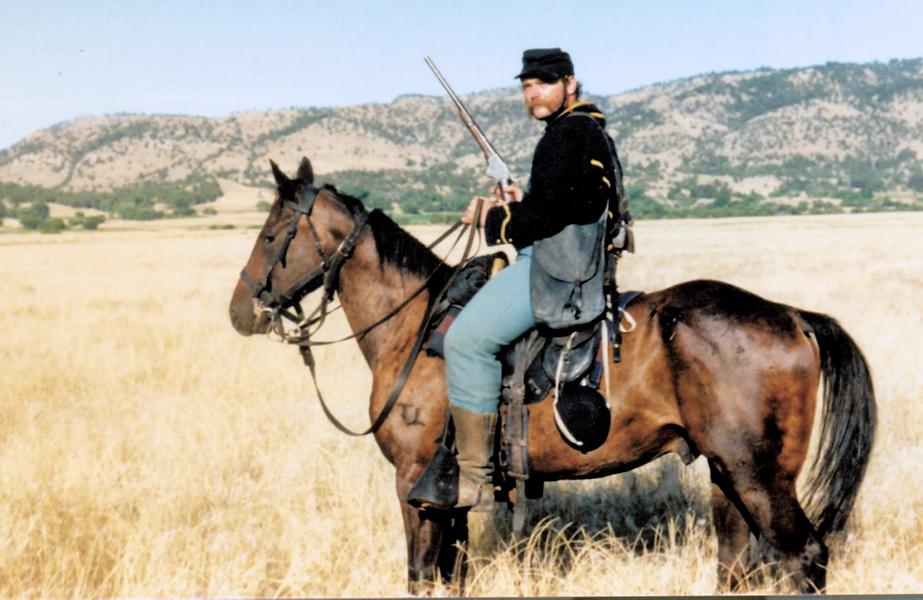

Hatzell on horseback from Fetterman Fight scene in TNT’s 1996 film Crazy Horse.

– All images courtesy Jim Hatzell unless otherwise noted –

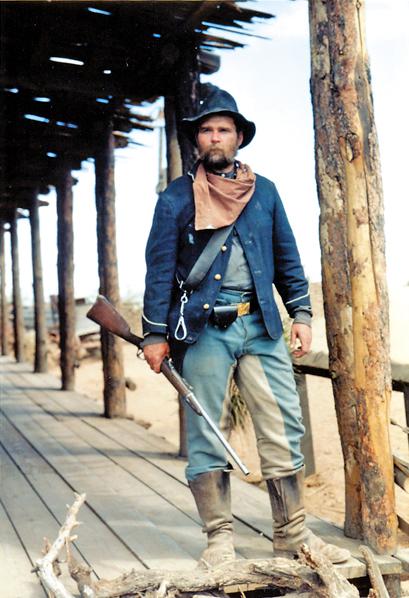

U.S. Cavalry and Apache Scouts in 1993’s Geronimo: An American Legend.