Secretary of War Jefferson Davis wrestled with a problem in 1840.

He needed to send soldiers to protect the vast Southwestern frontier, but little grass and scarce water meant horses and mules suffered terrible hardships. Many died. When Davis’s long-time friend George Perkins Marsh suggested he try camels, which could carry heavier loads on less feed and water, Davis jumped on the idea. It took him 15 years to convince Congress.

When Congress approved $30,000 for the experiment, Davis sent Maj. H.C. Wayne aboard the naval vessel Supply to buy 32 camels in Egypt. The camels were of two types: one-humped Arabian camels for riding and two-humped Bactrian camels for carrying heavy loads. The shipload of camels arrived in Indianola, Texas, in April 1856 with one extra camel, a calf that had been born at sea.

Overjoyed to be back on dry land, the camels cavorted about with glee, entertaining the local citizens, most of whom had never seen a camel before. The homely beasts had weathered the trip well, in spite of having to be tied down to the deck during storms so they wouldn’t be tossed overboard. The crew was happy to get off the ship too. The camels smelled awful and were seasick in rough weather.

A month later, Wayne traveled westward with his camels. In Victoria, he had the beasts clipped and gave some of the wool to Mary Shirkey. Mrs. Shirkey spun and knitted the wool into a pair of socks and sent them to President Franklin Pierce, who found that they smelled so horrible he could not wear them.

When the caravan arrived at the permanent quarters in Camp Verde in Texas Hill Country, the great Southwestern desert camel experiment began in earnest. Major Wayne put the animals to work carrying supplies between Camp Verde and San Antonio. If the caravan had not been slowed by the horses and mules, the trip would have taken two days instead of three. Six camels could carry more weight than 12 mules. The trip was so successful that a second shipload of camels arrived in Indianola in 1857. The time had come for the ultimate test.

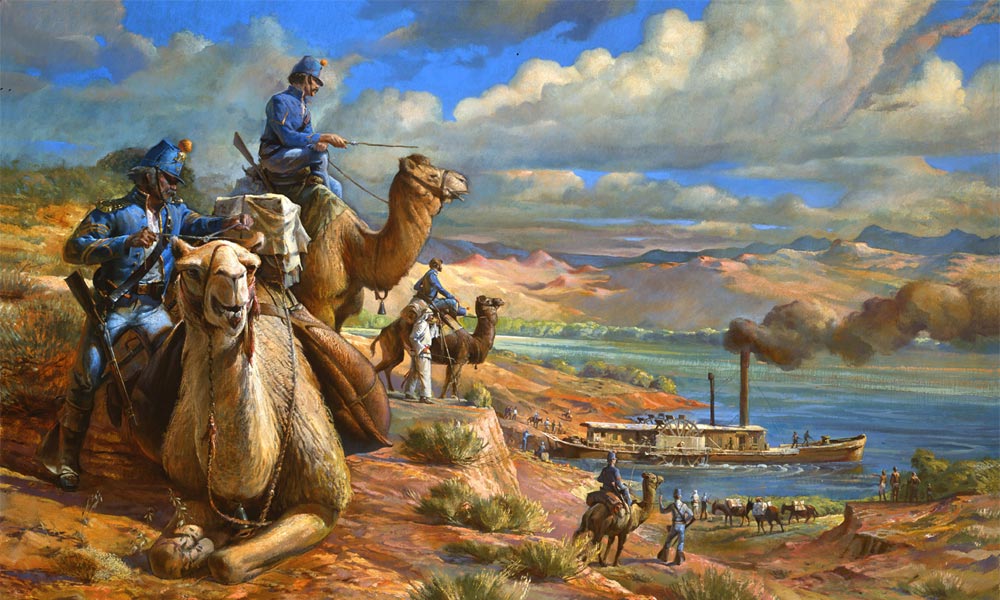

Lieutenant Edward Beale convinced Davis to let him take a caravan of camels to the far west. He started out from Camp Verde with 25 camels and 44 soldiers. Beale soon found that the relationship between the camels and the soldiers was deteriorating. Aside from their bad smell, the creatures were inclined to bite, and when the men moved out of biting range, the camels spit on them. They walked so fast that the horses and mules could not keep up. The horses and mules did not mind this lag; they were terrified of the awkward beasts.

Another group of camels traveled into the unexplored Big Bend Country of West Texas under the command of Lt. William H. Echols. The camels navigated rugged country carrying barrels of water needed for the survival of the soldiers and mules. The beasts thrived on thorny, desert plants that the mules couldn’t eat and went without water for days in the blazing heat. In his journal, Echols recorded these comments: “Country very rough, rocky, barren, dry apparently no rain on the region over which we passed today for a year. Every blade of grass dry and dead, not of this year’s growth. Our mules will not fare well no forage and a very limited supply of water. The camels have performed most admirably today. No such march as this could be made with any security without them.”

In many ways the camel experiment was a resounding success. When horses and mules collapsed in the desert from dehydration, the camels trudged on. No load seemed impossible for them to carry. One camel found its way into the infantry where Capt. Sterling Price used it to carry the baggage for his entire company.

If the camels had an Achilles’ heel, it was their wide, leathery feet. Perfectly adapted for travel over sand, a few of the animals suffered from walking on the rocks of the Southwestern desert. One became so lame that his feet had to be wrapped in circles of rawhide gathered around the ankles with a drawstring, much like huge ballet slippers. A greater number of horses and mules went lame on the rocks and had to be abandoned.

The U.S. Army’s interest in the Camel Corps waned with the onset of the Civil War. In 1863 the animals were auctioned off to the highest bidders, including zoos, circuses, mining companies and Beale himself. Those not sold were captured by the Confederate Army or turned loose in the desert.

For many years after the Army’s camel experiment, wild camels were sighted in the desert Southwest. Near a fort in New Mexico in 1885, a five-year-old boy was frightened by a strange animal with a hump, a long neck and shambling legs. It was an old Army camel trying to return to the post. The boy, Douglas MacArthur, loved to tell his story of the terrifying apparition he once saw in the desert.

For more than 100 years, this desert has been devoid of camels. But recently their distinctive, two-toed footprints have reappeared in the sands of Texas. The camels are treasured members of the Texas Camel Corps, the brainchild of Doug Baum, a former zookeeper with a love of camels and history. Were it not for his red hair, Baum could be mistaken for a Bedouin wearing a shemagh (headdress) and long, flowing robe.

He seats himself on the knee of Gobi, a 17-year-old Bactrian camel. As Gobi reclines in typical camel fashion beside his empty feed pan, it’s easy to see the affection the two share.

“I love this old guy,” Baum says. “He and I have been through a lot together. Once I took him upstairs in a freight elevator for an indoor performance. That’s an experience I’m not anxious to repeat.”

Pecos, Baum’s eight-year-old son, rides Gobi around the field near the Corps’ headquarters outside Valley Mills. Baum has six camels at present, some of which he acquired as babies and raised on a bottle. His camels appear in educational programs and re-enactments of the 1850s Army camel experiment. Three-day treks through the Big Bend area of Texas, an eerily beautiful, arid place where the original camels proved their worth, test the mettle of those who want to re-create history. The treks focus on the natural history and ecology of the Chihuahuan Desert. Another trek at Monahans Sandhills State Park, which sports some 70-foot sand dunes, mimics life among the Bedouins. Here Baum does overnight treks in which the camels carry gear, food and water. The people walk, leading the camels behind them.

Before he began to take camel trekkers into the desert, Baum was tutored by a Bedouin family in Egypt on the nuances of camel handling.

“Camels are highly sensitive and easily insulted,” Baum says. “To get the most out of them, you have to treat them with fairness and remember that they have motivations of their own.”

Under Baum’s care, he’s seen no evidence of the biting and spitting behavior that so offended 19th-century soldiers. The animals seek out his attention, rubbing their heads lovingly against his arm and occasionally knocking off his hat. Perhaps centuries spent on horseback prejudiced the early soldiers against the animals. It is hard to see the camels as spiteful when Baum’s son stands beside Gobi—who tips the scales at well over 2,000 pounds—says “Couche” (French for “lie down”) and is rewarded with immediate obedience as the camel kneels so his small handler can climb aboard.

For 10 days of each month, Baum works with groups of at-risk teens at VisionQuest. He spends part of each session teaching camel-handling skills and the rest accompanying his charges on a three-day trek through Arizona’s Coronado National Forest.

The Texas Camel Corps keeps Baum fairly busy. The camels have appeared in movies and commercials, carried the Wise Men to Bethlehem in countless Christmas re-enactments and helped raise money for Kenya’s Camel Library, which delivers books to the children of nomadic tribes in Kenya’s northeastern province. In between these engagements, Baum leads camel treks in Egypt and spends time teaching camel-handling skills to his own three children: Pecos, Delany and Vanessa. Fifteen-year-old Vanessa already handles the animals like a pro. It’s a good thing, since the entire family is often called on to help out with performances.

“Once we took the camels, one of our donkeys and three borrowed sheep for a Christmas performance in Waco, and the sheep emancipated themselves near a busy highway,” Baum says. “We had a few tense minutes there, before we got them back in the pen. I learned to appreciate my placid camels that day.”

It’s a real head turner to drive along deserted FM 56 outside Valley Mills and see camels browsing in the trees near the road. Sometimes people stop to ask for a closer look at them. Doug Baum doesn’t mind. It gives him a chance to tell them the story of the first camels to come to the Texas plains, way back in 1856.