“Chisum! John Chisum! Weary. Saddle worn.”

“Chisum! John Chisum! Weary. Saddle worn.”

Sorry. Every time I think of John Simpson Chisum, I think of the 1970 John Wayne movie Chisum, and Andrew J. Fenady’s theme song.

OK. Though highly entertaining, Chisum isn’t a classic movie, and Fenady’s probably better known for the theme song “Johnny Yuma” for his TV hit The Rebel, but Chisum—Fenady also produced and wrote the screenplay—has always been a guilty pleasure of mine. And William Conrad’s voice just gives me goose bumps:

“They say that you can’t make it. Will you hark to what they’ve said? Or will you move your beeves from Texas across the River Red? They’re betting you can’t make it. But you bet your life they’re wrong. So keep riding toward the Pecos to find where you belong.”

So here I am, in Texas, not far from that Red River, when suddenly it hits me. If Chisum is taking his cattle to New Mexico, why would he cross the River Red?

Oklahoma isn’t exactly on the way.

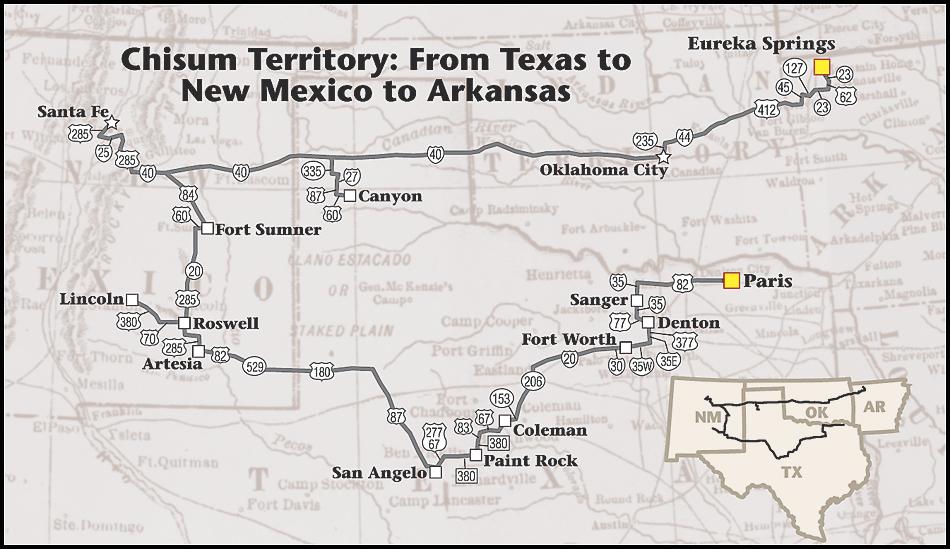

But Paris is where the John Chisum story begins, even if he was born in Tennessee in 1824. By 1837 he was in Texas. He clerked in a store in Paris, and would hold office as Lamar County clerk from 1852-54. He even operated several groceries. After he died in 1884, he was buried here, resting beside his parents, Claiborne and Lucinda.

They haven’t forgotten Chisum here. Last May, the local VFW Post put on “John Chisum Days” at the Red River Valley Fairgrounds. And at the Paris Public Library, Jerry Bywaters painted a three by six-foot mural as part of the Public Works of Art Project back in 1934. The mural even looks like John Chisum, and not Duke Wayne. Bywaters was a Paris native, but I’m doubting Bywaters would have painted John Chisum had Chisum stuck to grocery stores. And I can’t picture the Duke playing a grocery baron in a movie.

Chisum teamed up with Stephen K. Fowler of New Orleans and entered the cattle business in Denton County—which meant Chisum would have crossed the Trinity River, not the River Red.

Near Sanger, about three miles north of Bolivar—you take Chisum Road and Jingle Bob Trail to get there—is a 1936 Texas Centennial Marker on the site of Chisum’s home—known as the White House—from 1856-62. Of course, the marker has Chisum dying on September 22 (it was December 22) in Paris (it was Eureka Springs, Arkansas). Another marker, erected by the Texas Historical Commission in 1970, notes the town of Bolivar, founded in 1852, and mentions Chisum as a “Texas cattle baron, who had herds here and furnished beef to the Confederacy during the Civil War.”

If you need something more substantial than roadside markers for your history, head to Denton and the Courthouse-on-the-Square Museum, located on the first floor of the 1896 courthouse. Or, better yet, spend plenty of time in that classic cow town, Fort Worth.

By the 1860s, Chisum had established himself as a cattle baron, running 5,000 head and owning six slaves in North Texas. When the Civil War broke out, instead of joining the Confederate army, Chisum was placed in charge of cattle herds. In 1862, he drove a herd to Confederate forces near Vicksburg, Mississippi, but a year later he was again on the move.

Ending his partnership with Fowler, Chisum moved toward the Concho River country. Before long, Chisum and his new associates had roughly 18,000 head of cattle. Around this time, Chisum came up with his brand, the Long Rail, and his ear-lopping technique, the Jinglebob.

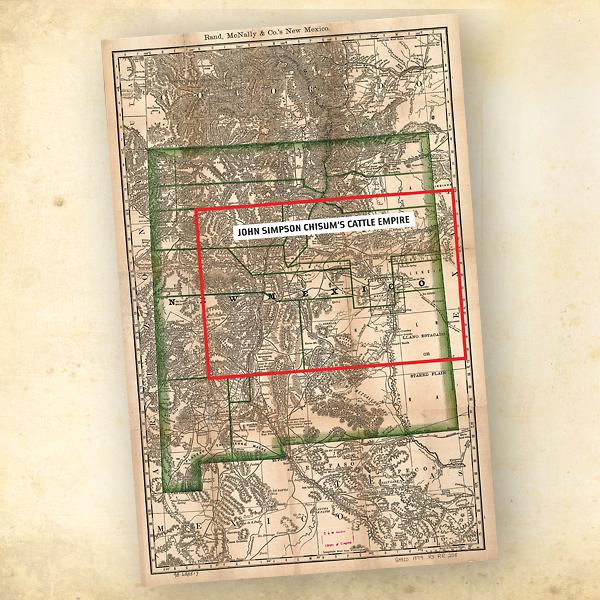

After the Civil War, he drove cattle to Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory, and even partnered with another cattle legend, Charles Goodnight. By 1872, Chisum had left Texas and set up a cattle ranch along the Pecos River in southern New Mexico Territory.

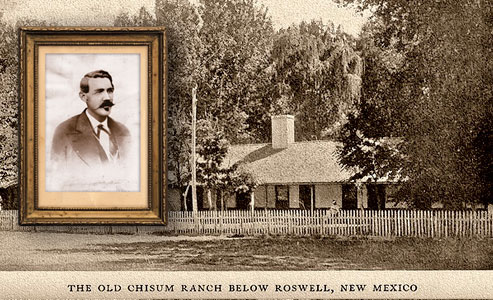

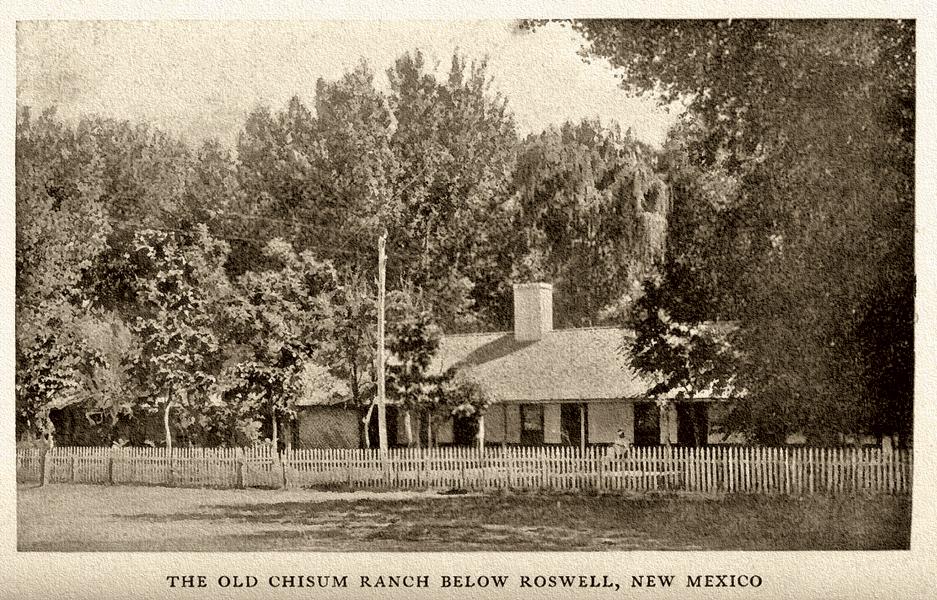

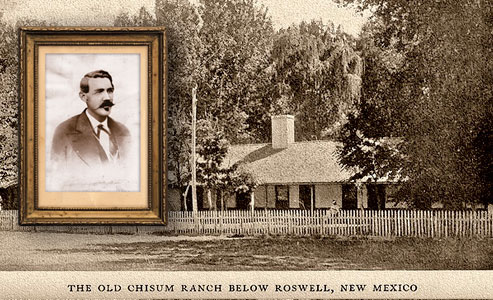

By 1867, his ranch was headquartered at Bosque Grande, about 35 miles north of Roswell. Soon, Chisum was the “King of the Pecos,” and in 1875 he moved his ranching headquarters to the South Spring River, four miles southeast of Roswell.

His empire grew, and then a little event called the Lincoln County War erupted.

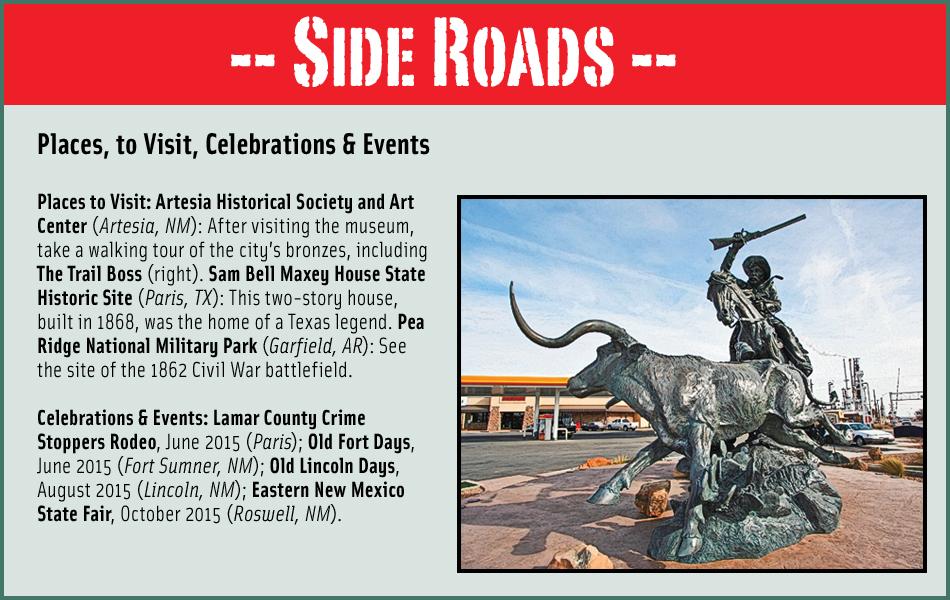

But before we get to Lincoln, we need to tip our hats to Chisum’s niece, Sallie (his brother Pitzer’s daughter). For that, head to Artesia, New Mexico, and check out the bronze at South Third and West Main streets. “The First Lady of Artesia,” Sallie was about as ambitious and independent as her uncle. Settling in Artesia in 1890, she would be a major player in real estate, serve as postmistress, run a boardinghouse, help the sick, befriend children and develop businesses. She left Artesia in 1919, and died in Roswell in 1934. The bronze by Robert Summers was dedicated in 2003.

On the other hand, Chisum gets his own bronze in Roswell. Located across from the county courthouse on the Roswell Pioneer Plaza, the bronze, also sculpted by Summers, was dedicated in 1999.

Most people picture extraterrestrial life-forms when they think of Roswell, but it’s much more than that. Yes, the International (shouldn’t it be Universal?) UFO Museum and Research Center sits on Main Street, but this is a cosmopolitan city. The Roswell Museum and Art Center includes works by Peter Hurd and Georgia O’Keeffe, but my favorite gallery is the West of Beyond collection. Rogers Aston didn’t begin sculpting until he was almost 40 years old, and the props he used were certainly authentic. As Tom Lovell, who later mentored under Aston said, “One may be certain that if a weapon or costume is portrayed [in Aston’s work], it is correct.”

Now, on to Lincoln.

If you don’t know about the Lincoln County War, you’ll certainly learn about it in New Mexico at these three excellent historic sites and museums: The Lincoln State Monument in Lincoln, which hasn’t changed much since the 1870s, although the mortality rate isn’t quite as oppressive these days; the Billy the Kid Museum and Old Fort Sumner Museum in Fort Sumner; and the New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe.

In a nutshell, the war, which erupted in 1878, pitted the factions (including Billy the Kid) of attorney Alexander McSween and rancher/merchant John Tunstall (backed by Chisum) and the powerful “House” ruled by Lawrence G. Murphy and James Dolan (backed by the Santa Fe Ring).

I always liked the line Royal B. Hassrick put in his slim volume The Colorful Story of the American West describing Chisum and Murphy as “two willful men, each with a reputation that smelled like a dead cow.”

By 1880, with Murphy, McSween and Tunstall long dead, Chisum was feuding with Billy the Kid. In Fort Sumner, Billy said the cattleman owed him money. Chisum’s response:

“Billy, you know as well as I do that I never hired you to fight in the Lincoln County War. I always pay my honest debts. I don’t owe you anything, and you can kill me but you won’t knock me out of many years. I’m an old man now.”

Said Billy: “Aw, you ain’t worth killing.”

Billy was dead a year later.

John Chisum wasn’t far behind.

So now it’s back east, through the Texas Panhandle (Charles Goodnight country, but make a stop at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon), through Oklahoma (stop in at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City), and into Arkansas.

Chisum wound up at Eureka Springs—a charming little Ozarks town—but not to shop for antiques or crafts. On July 7, he had had surgery for a growth on his neck in Kansas City. He came to Eureka Springs hoping for a miracle cure.

It didn’t happen. He was dead from cancer a few days before Christmas 1884.

Fenady’s fine lyrics run through my mind again (OK, I’m actually singing them):

“Well, you’ve crossed beyond the Brazos. Fought Comanches, rain and sand. You’ve brought your cattle westward. But is this your promised land? You’ve made it to the Pecos. Carved your empire ’neath the sun. You’ve won a hundred battles. But the fight keeps going on.

“Chisum. John Chisum. Weary. Saddle worn. Chisum. John Chisum. Can you still keep going on?”

Alas, the answer is nope. After his death, Chisum’s cattle empire fell apart, and, as Frederick Nolan writes, “by 1891 it was little more than a memory.”

PLACES TO VISIT, CELEBRATIONS & EVENTS

Places to Visit: Artesia Historical Society and Art Center (Artesia, NM): After visiting the museum, take a walking tour of the city’s bronzes, including The Trail Boss (above). Sam Bell Maxey House State Historic Site (Paris, TX): This two-story house, built in 1868, was the home of a Texas legend. Pea Ridge National Military Park (Garfield, AR): See the site of the 1862 Civil War battlefield.

Celebrations & Events: Lamar County Crime Stoppers Rodeo, June 2015 (Paris); Old Fort Days, June 2015 (Fort Sumner, NM); Old Lincoln Days, August 2015 (Lincoln, NM); Eastern New Mexico State Fair, October 2015 (Roswell, NM).

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub: Scholl Bros. Bar-B-Que (Paris, TX); The Dolan House (Lincoln, NM); The Santa Fe Bite (Santa Fe, NM); Cattlemen’s Steakhouse (Oklahoma City, OK); Café Luigi (Eureka Springs, AR).

Lodging: The Worthington Renaissance Fort Worth Hotel (Fort Worth, TX); Burnt Well Guest Ranch (Roswell, NM); Hotel La Fonda (Santa Fe, NM); Skirvin Hilton Hotel (Oklahoma City, OK); Best Western Inn of the Ozarks (Eureka Springs, AR).

GOOD BOOKS/FILM & TV

Good Books: To Hell on a Fast Horse: Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, and the Epic Chase to Justice in the Old West (Mark Lee Gardner); The Story of the Outlaw (Emerson Hough); John Chisum: Jinglebob King of the Pecos (Mary Whatley Clarke); The West of Billy the Kid (Frederick Nolan.)

Good Films & TV: Chisum (Warner Bros.); Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Warner Bros.); Young Guns II (20th Century Fox).

Johnny D. Boggs figures that Andy Fenady used the “River Red” line as a tribute to John Wayne’s classic movie Red River—or because South Spring River doesn’t rhyme with “said.”

Photo Gallery

– All photos by By Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –

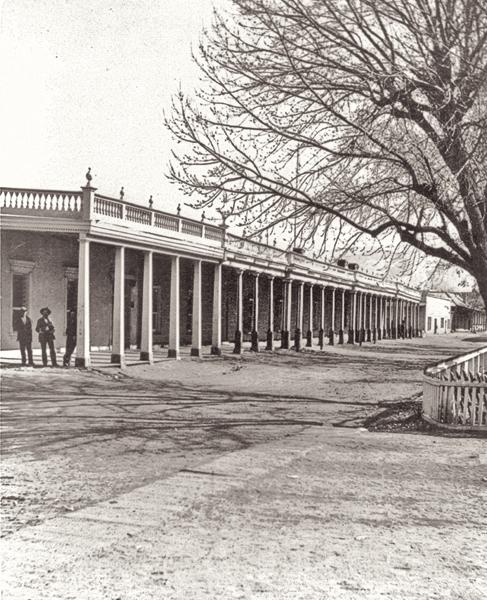

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– All photos True West Archives –

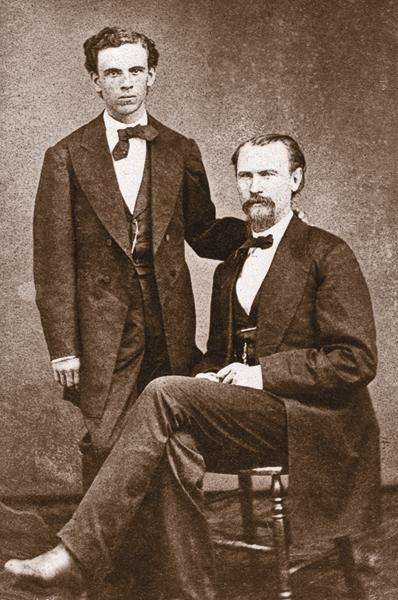

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

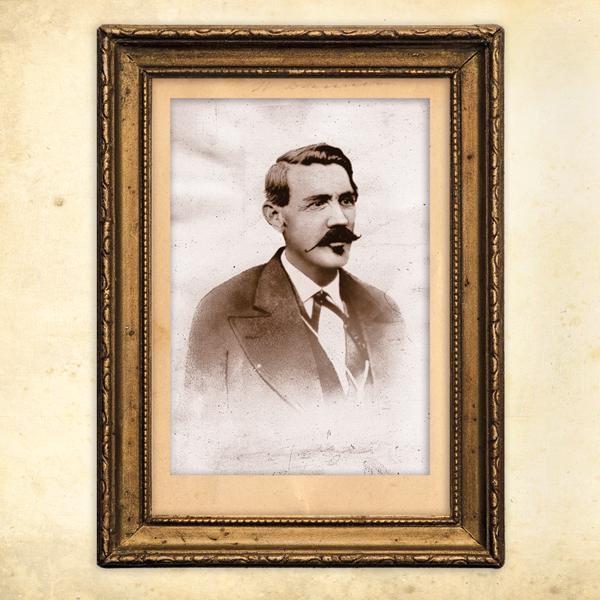

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

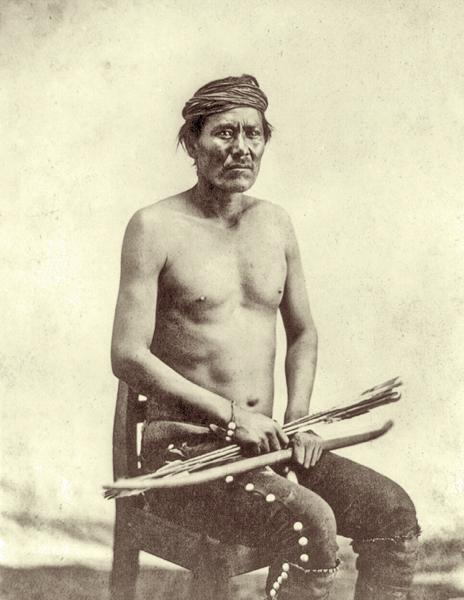

– Courtesy Library of Congress –