Standing outside Due West Gallery, Thom Ross is packing iron.

Standing outside Due West Gallery, Thom Ross is packing iron.

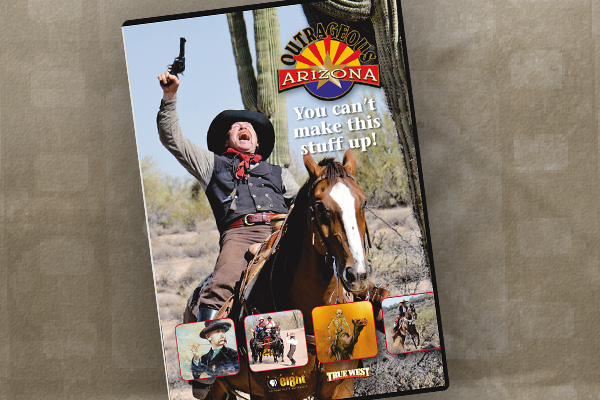

Good thing Wyatt Earp and Pat Garrett aren’t in Santa Fe, New Mexico, or they’d be hauling Ross off to jail for violating that checked gun policy.

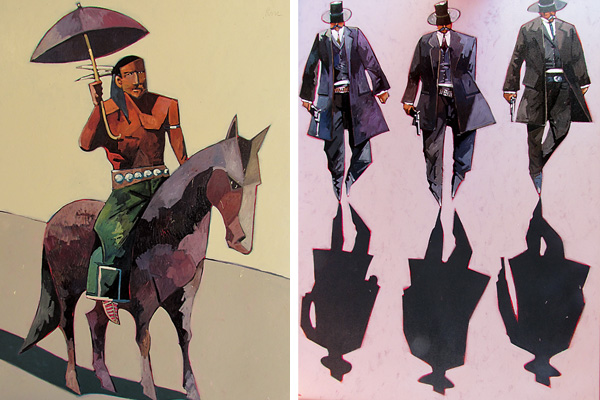

Wait a minute. Earp and Garrett—and Billy the Kid, Johnny Ringo, Buffalo Bill Cody, even boxer Jack Johnson—are in Santa Fe, hanging on the walls of Due West Gallery, where you’ll also find the artwork of Duke Beardsley, Maurice Turetsky and others, including Bob Boze Bell (but that’s not why we’re covering this in the magazine).

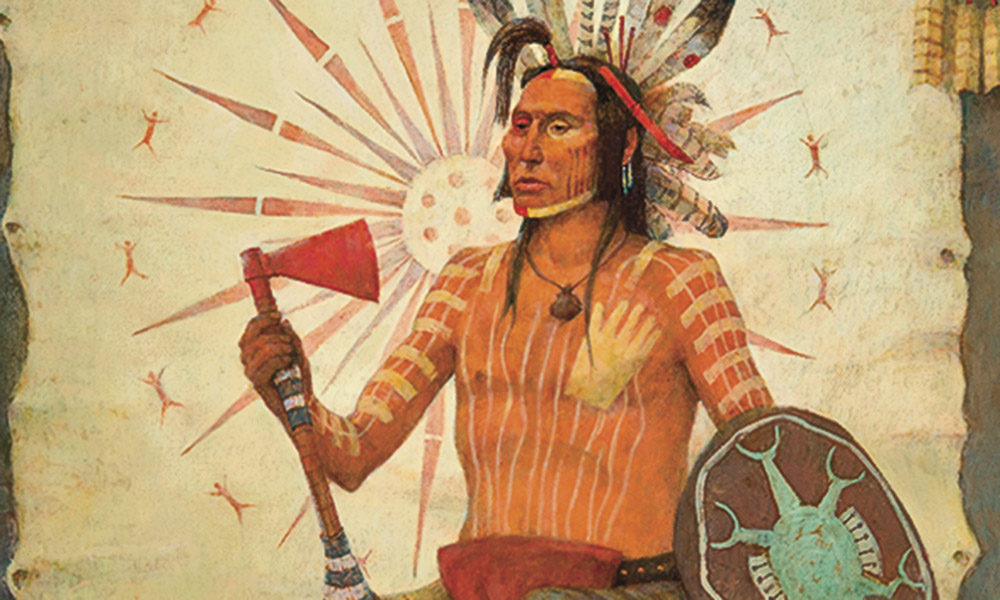

We’re writing this because we like Ross, his gall and gumption, and his no-holds-barred approach to art and history. “The majority of Western artists are bad historians—if they do any research at all,” says Ross, inside the gallery he started last year. “This is where Western art gets slammed—correctly. Because it’s not art. It’s picture making. Look at an artist like van Gogh, and his painting Corn Field with Ravens. I love ravens, and I love cornfields. But when he paints it, the painting itself is what’s so seductive.”

Most Western artists will mention Charlie Russell or Frederic Remington, but Ross cites Vincent van Gogh (another reason we like him). “People get so into ‘A Western painting has to look like this,’” he says. “Well, give me something where you are out of the box.”

That’s why Ross, who grew up in Sausalito, California, and moved to Santa Fe from Seattle, Washington, started Due West. Santa Fe’s the third-largest art market in the United States, but the city has probably never seen a gallery like Due West or an artist like Ross in decades—if ever. Ross puts bold, contemporary takes on Western history. He doesn’t hold back in his paintings, or when he’s speaking his mind.

One thing you won’t find in Due West: That stupid painting of a cowboy wearing a yellow rain slicker as he rides down a mountainside. “Give me a break,” Ross says. He actually adds a few other choice adjectives, which is why my 10-year-old son calls Ross, “Potty-mouth Thom.”

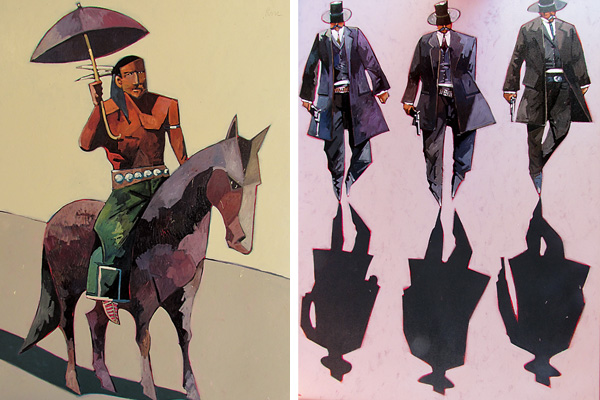

What you will find are paintings like Indians Playing Golf, which depicts, you guessed it, Indians playing golf. As soon as Ross mentions that, a couple walks down San Francisco Street, stops to admire the painting in the window, smiles, laughs, points, then moves on.

But that image didn’t come to Ross in a dream. It’s historic. History fuels Ross’s passion. “Most artists reproduce and reproduce without getting closer to what I call the truth,” he says. “The danger is learning how to separate the truth from the myth. As an artist, you should be looking into that myth. Why does Custer’s Last Stand matter? Why are they still making movies about the Alamo and Billy the Kid and Wyatt Earp? We project our emotions through these figures, and there’s something really wonderful about it.”

It’s probably no surprise that Ross’s favorite novel is Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. “I thought it was about a guy who wanted to go kill a whale,” he says. “Then my English teacher said, ‘That’s what the story’s about, but that’s not what he’s talking about. He’s talking about man and God and the universe….’ I said, ‘You mean you can hide meaning in the confines of reality?’ He said, ‘Yeah, absolutely.’ And I said, ‘That’s what I want to do with my art.’ I’ll tell the historical story, but it’s not going to be focused on historical minutia.”

Johnny D. Boggs wonders when Thom Ross plans on reclaiming the plywood paintings of Custer and Sitting Bull he loaned out for a party in January.