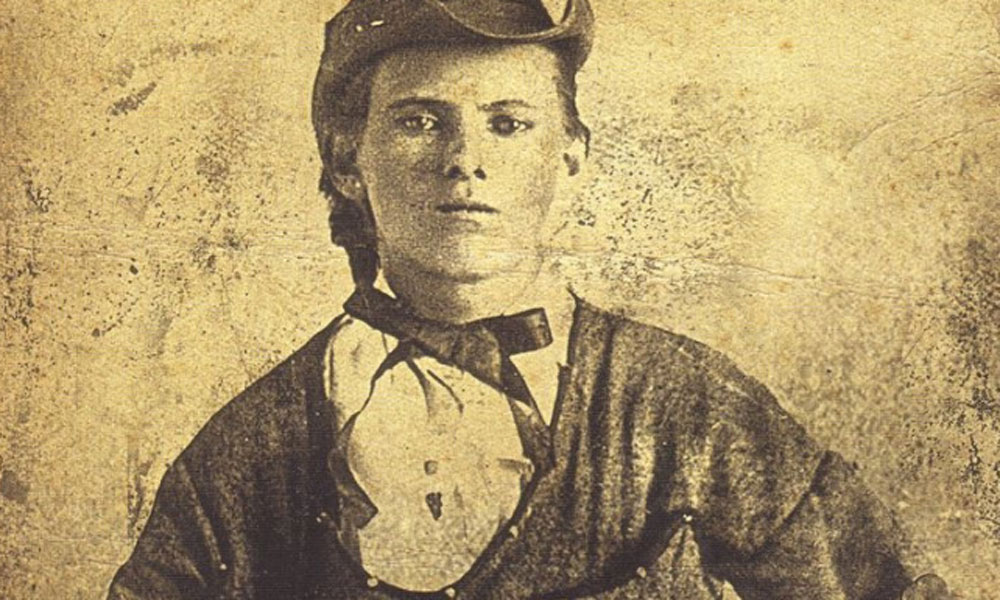

Most Jesse James buffs take as gospel that the famous bandit invented the daylight bank robbery and that he was never arrested. Both of these accepted truths are false.

Most Jesse James buffs take as gospel that the famous bandit invented the daylight bank robbery and that he was never arrested. Both of these accepted truths are false.

Myth # 1: Jesse James invented the daylight bank robbery.

On February 13, 1866, between 10 and 13 men, likely led by former Confederate guerrillas George Shepherd and Arch Clements, robbed the Clay County Savings Bank in Liberty, Missouri. They made off with over $57,000. It was the first daylight bank robbery in peacetime U.S. history.

Later it was claimed that Jesse James pulled off the robbery, aided by his gang and his brother, Frank. Though Frank may well have taken part in the holdup, Jesse was probably home in bed three miles east of Kearney, Missouri, with a near fatal lung wound.

Just before the theft, two men identified as Frank James and Bud Pence reportedly obtained two sacks of meal from B.S. Minter. The sacks were reportedly the same ones used to carry away loot from the robbery. Minter later claimed that he didn’t know the men, although he had told neighbors they were Pence and Frank James. In any event, the Clay County Savings Bank building is now called the Jesse James Bank Museum, and a number of books date the outlaw career of Jesse James from the 1866 Liberty holdup.

Myth #2: Jesse James was never arrested.

Clay County, Missouri, was a Democratic strong-hold. During the November 1866 county election, however, a small pro-Union minority held sway because the Test Oath had disenfranchised many Southern sympathizers. Tensions were so high, Liberty Sheriff James M. Jones and his deputy, Joseph Rickards, requested troops from Fort Leavenworth, deeming “the lives of Union men [to be] in great danger at the present time in this county, several of the most respectable citizens have been ordered to leave and many others have been publicly insulted and their lives threatened.”

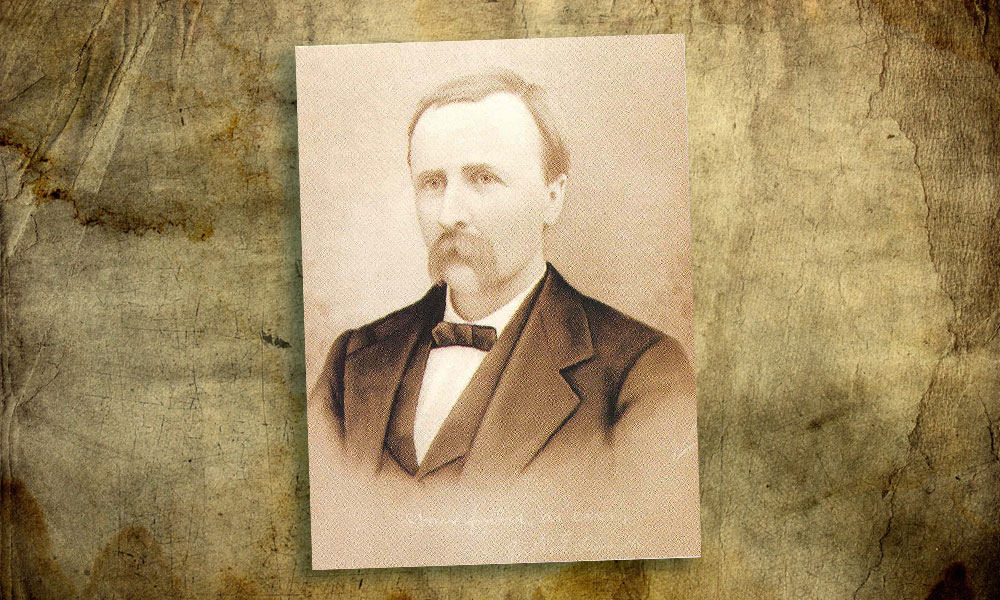

The following account was taken from a subsequent interview with Judge Philander Lucas of Missouri’s Fifth Circuit Court (published in the Washington Post and reprinted in the Cincinnati Enquirer, on July 26, 1902).

I was a Democrat, but had served in the Union army during the war, while my Sheriff, Joe Rickards, was a Republican. While my appointment was satisfactory and popular with the people of my circuit, Clay County was somewhat opposed to Joe because of his politics. However, Joe was a good officer, and not afraid of any man living. . . . One day a man named Sam Holmes arrived at the courthouse with a verbal message for Rickards from Frank and Jesse [James], who that day had been at the Platte County fair making themselves generally obnoxious, to the effect that they were coming to Liberty on the day following and that ‘no d—d Republican could arrest them’.

This was clearly a dare or a challenge, and, although Rickards was not a man for unnecessary trouble and quarreling, he was not the sort of person to put up with any such impudence as this. He came to me about it, telling me of the message the James boys had sent. When he finished I asked him what he was going to do. He did not say a word, but, turning, gave me a very comical and significant wink.

Rickards’ wink meant more than words, and on the following day I remained on the qui vive to see what would happen. I did not want to see Rickards get hurt nor allow himself to be drawn into unnecessary trouble, but at the same time I relied on his good judgement to do the right thing in the right place and time. Besides, it was high time that some one was taking the conceit out of these little game roosters who were dropping in every day or two from a four year course in bushwhacking, and who were trying to turn the country upside down with their crazy exploits.

Along about 11 0’clock, while I was standing on the sidewalk opposite the courthouse, in rode the whole bunch—Frank [James], Jesse [James], Gus Claybrooke, Clel Miller, Jim Poole and George White. They did so in a very disorderly way, yelling, firing off their revolvers, swearing, and acting in a manner thoroughly objectionable. They dismounted and went in Fred Meffert’s saloon. As they did so I looked about to see if I could see Rickards, and sure enough, there he stood, right opposite the saloon, with his hat pulled down over his eyes and wearing an old overcoat in which he had never appeared. The gang had ridden right past him without noticing him. The minute they entered the saloon Joe followed, and just as he appeared he drew forth from under the old overc[o]at two six-shooters, which he leveled at the gang abef[o]re him and said: “Throw up your hands.” They turned, saw what was confronting them, and obeyed very quickly. Then, as they did so, Joe said: “Now, then, you—scoundrels, you said that no—Republican could arrest or take you; I’ll show you a trick or two about that.”

As he stood with the two revolvers leveled at their heads, a Deputy removed the pistols and belts from each, and, when this was finished, Joe marched them over to the courthouse before me. As a matter of fact there were at that time no charges against any of these men, as what killing and robbing that they had done had been committed in time of war and as an act of reprisal on an enemy. After some palaver and efforts on the part of Joe to find some charge against the men, with a warning from Joe to in the future mind their p’s and q’s, we were obliged to turn them loose.

This taught the James boys and their confederates a lesson they never forgot. . . . this was the first and only time he [Jesse James] was ever arrested, and it is just a little re-markable that when it happened the Sheriff had no charges upon which to hold the greatest of Amer-ican outlaws.

It wasn’t until the robbery of the Daviess County Savings Association in Gallatin, Missouri, on December 7, 1869, that Frank and Jesse James were ever formally connected with any robbery. The story of their arrest never saw any ink in the pro-Democrat Liberty Tribune and was largely forgotten. Detective Robert Pinkerton att-ested to the story in a note to his brother, William (now in the Pinkerton Archives at the Library of Congress): “I remember when I first heard of the Jameses was after the Corydon, Iowa Bank Robbery [in 1871]. When we followed the Jameses into Clay County from the scene of the robbery. . . at that time I heard of former Sheriff Rickards arresting the Jameses.”

It would go down in popular lore, however, that Jesse James was never arrested.

Ted P. Yeatman is author of Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend and numerous articles about the James brothers and other Western outlaws and gunmen.

Photo Gallery

– Photo courtesy Library of Congress –