Because of their unusual looks, Merwin, Hulbert & Co. firearms have been considered the “ugly ducklings” of frontier six-shooters.

Because of their unusual looks, Merwin, Hulbert & Co. firearms have been considered the “ugly ducklings” of frontier six-shooters.

For years, scant documentation on Merwin Hulbert revolvers resulted in the company being overlooked by serious arms students and collectors. Thus one could pick up guns by this 19th-century company for considerably less than other makes of the same era.

Yet, for the past couple of decades, Merwin Hulbert revolvers have been commanding prices more in keeping with their historic value and distinct, innovative styling.

Merwin & the Hulberts

The few surviving factory records indicate that Merwin, Hulbert & Co. was initially organized around 1869, under the name “Merwin & Hulbert.”

It was organized as an import/export arms distributing company, when Joseph Merwin, a New England arms marketer with an inventive genius and a knack for promotion and salesmanship, joined forces with William and Milan Hulbert. The two brothers from Brooklyn, New York, had enjoyed a fair degree of success as businessmen and financiers, and were able to secure investment capital.

Through the acquisition of half interests in the Phoenix Rifle and Ammunition Co. and the American Metallic Cartridge Co., the company’s name was changed sometime during the early 1870s to “Merwin, Hulbert & Co.”

Starting in 1871, Merwin Hulbert served as sales representatives for Hopkins & Allen, a firearms manufacturing enterprise in Norwich, Connecticut. Three years later, the company purchased stock from Charles A. Converse, one of the founding shareholders of Hopkins & Allen, to gain an equal partnership in Hopkins & Allen.

Merwin Hulbert also invested $100,000 in the Evans Rifle Company, thus forming the complete company.

The new firm soon became the world’s largest dealer in firearms and related accessories. For years, Merwin Hulbert profited not only from producing quality guns, but also from representing most of the major arms manufacturers and handling a complete line of related firearms goods like sights, loading tools, decoys, hunting gear and outdoor clothing.

Besides representing their own firms, Merwin Hulbert became sales agents for well-known domestic arms companies such as Colt, Winchester, Marlin, Remington, Ballard, L.C. Smith, Parker and Ithaca. The company also represented British makers like W.W. Greener, Westley Richards and Manton. So complete was the Merwin Hulbert line of sporting goods that its illustrated catalog was well over 150 pages thick and included non-gun sporting items for gymnastics, fencing, fishing, boating, boxing, tennis, baseball and more—including bicycles (which were then quite the rage). It was the most encompassing arms company catalog of the day.

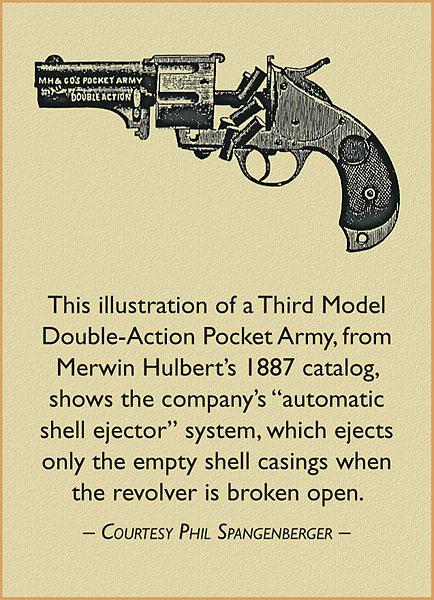

In 1876, Merwin Hulbert began producing a line of its own creations

at the Hopkins & Allen plant in Norwich. These Merwin Hulbert handguns were extremely well made—Joseph Merwin himself took personal interest in their development. The revolvers carried some of the most advanced features of the period like an automatic shell ejector, which ejected only the empty cartridge

shell casings when the revolver was broken open.

The company went on to manufacture both single-action and double-action revolvers under the strictest quality control methods and machined them to remarkably close tolerances. Early models were of the open top variety, while later versions were produced with a top strap on the frame.

An example of the company’s precision fitting is the vacuum created when the barrel is pulled forward for cartridge extraction. When pulled forward and released, the barrel assembly is automatically withdrawn back into position due to the extreme precision tolerances—a phenomenon not found in any other firearm.

Merwin Hulbert revolvers found today in good condition will automatically return to the closed position when opened, if not manually held open. Further, these Merwins can be dismantled for cleaning or changing barrels—in just two quick motions—without using any tools. The rear of the cylinder is covered to keep the cartridges clean and free of dust, mud and other foreign debris that would prevent the firing pin from properly striking a cartridge’s primer, and none of the gun’s small parts are exposed to rust, damage or other obstructions.

A Unique Design

Given the company’s own unique design, rugged construction and well-finished pistols became a trademark of Merwin Hulbert.

For instance, in those days, other arms companies charged extra for nickel-plated arms (a distinct advantage in the age of highly corrosive black powder ammunition). Yet since the nickel-plating process employed by Merwin Hulbert produced arms that boasted of such a high quality and handsome finish, the company wisely offered nickeled guns for the same price as those wearing the blued finish. Only about one gun in 20 left the factory wearing a blued finish, and Merwins sporting any bluing are seldom encountered nowadays.

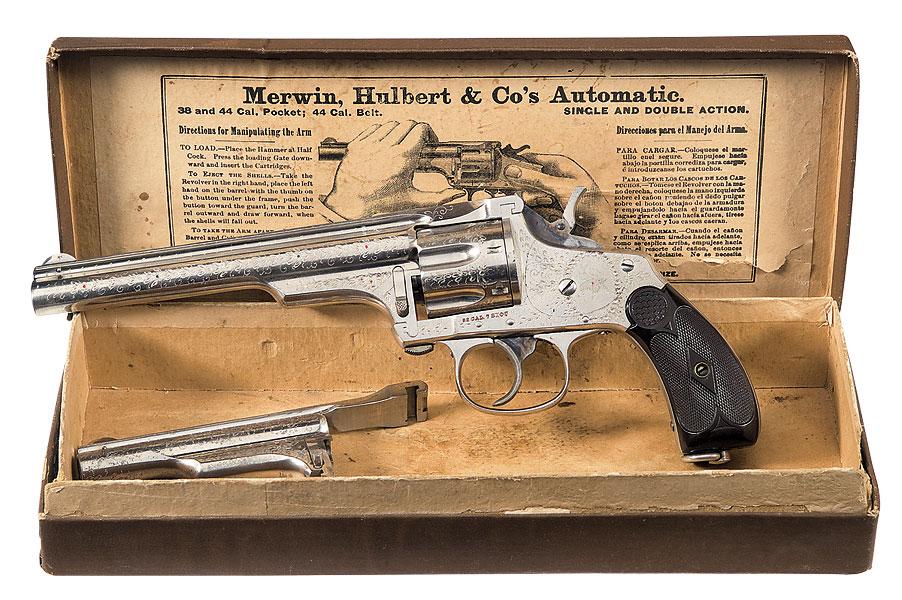

Merwin Hulbert also utilized a technique that was faster and required less study than incised engravings found on other arms. The company’s engraved models featured an embellishment known as “punch dot” engraving, referred to in Merwin Hulbert catalogs as “Intaglio Engraving.” Scrolls, borders and designs such as flowers were crafted via a pattern of tiny dots made by a punch-like tool tapped with an engraver’s hammer. It created a striking form of adornment that cost a fraction of the incised type of coverage.

The company produced a variety of handguns, ranging from small spur trigger .22 and .32 caliber rimfire and centerfire pocket pistols and mid-sized .38-bore revolvers, to large-framed belt and holster six-shooters (with trigger guards) in .38 and .44 caliber centerfire—including models with interchangeable barrels, folding hammers and quick replacement cylinders.

While the company’s stampings vary in placement on different models, its firearms are generally stamped somewhere with both the “MERWIN, HULBERT & CO., New York U.S.A.,” along with various patent dates, and the “HOPKINS & ALLEN Manufacturing Co., Norwich, Conn. U.S.A.” factory markings.

Collectors should note the different chamberings Merwin Hulbert produced for its .44-bore six-guns. For example, Merwin revolvers that are stamped on the left side of the frame with “CALIBRE WINCHESTER 1873” are chambered to take the popular .44-40 cartridge (a 200-grain lead bullet with 40 grains of black powder), while guns with no caliber designation, or stamped with “CALIBRE 44 M&H,” take Merwin’s proprietary round, which carried a 220-grain lead bullet, pushed by 30 grains of black powder (.44-30), although such revolvers are scarce—as are any chambered for the .44 S&W Russian loading (a 246-grain lead bullet and 20 grains of black powder). While the majority of the large-framed Merwin Hulberts are in .44-40 caliber, the .44-30 cartridge gained such favor south of the Rio Grande that the company’s catalogs labeled it “For Mexican Trade.”

Economic Depression

For a while, in the late 1870s or early 1880s, Merwin Hulbert, which competed primarily with Smith & Wesson for overseas contracts, also enjoyed brisk foreign sales in several countries such as Mexico, Spain, Great Britain and Russia. The company’s Russian sales were among its largest orders, until the Czarist government started producing its own versions of Merwins, as well as Smith & Wesson revolvers, in its Tula Arsenal (the equivalent of America’s Springfield Armory), very likely without paying licensing fees or royalties of any kind. (The Czarist government probably did not pay for vast amounts of Merwins already delivered, thus dealing the firearms company a deadly blow, since the company had expanded to meet the Russian’s production demands.)

Other factors that plagued the company were the failure of the Evans Rifle Co. and the alleged theft of company funds by a trusted associate. After Joseph Merwin’s untimely death in 1879, the firm’s situation plummeted to such a depressed economic state that by 1881, it went into receivership.

Quickly reorganized, the newly refinanced company was succeeded by the Hulbert Bros. & Co., in partnership with Hopkins & Allen. Although the new company struggled to continue producing revolvers, by 1896, this firm too had gone under, finally signaling the end of Merwin Hulbert firearms and their related goods.

Even so, Hopkins & Allen continued to manufacture Merwin Hulberts until around 1898, although these later-manufactured arms were stamped with only the Hopkins & Allen logo. Merwin Hulberts were still listed in the 1899 jobber price list as being available in .32 through .44 calibers. Although Hopkins & Allen continued producing its own guns until 1915, this firm suffered a disastrous fire in 1900 that burned the factory to the ground—destroying virtually all of both company’s sales and manufacturing records.

Its Best Customers

During the Merwin Hulbert production period, its revolvers were well received on the Western frontier, but perhaps even more so in the Eastern cities, where, contrary to the myth of the “Wild and Wooly West,” crime statistics showed that these heavily populated areas east of the Mississippi River experienced more street gangs, pickpockets, killings, robberies, rapes, prostitution, drug addiction and other criminal activities—including organized crime (the Sicilian Mafia, Chinese Tongs and other underground organizations).

Merwin Hulbert’s .32 and .38 pocket revolvers were apparently quite well favored by many private citizens, as well as law-enforcement officers, and many were purchased by police departments around the country. Merwin Hulbert revolvers were reportedly put to use by police departments in Augusta, Brooklyn, Boston, Cleveland, Charleston, Cincinnati, Detroit, New Orleans, New York City, Portland, Maine, San Francisco and Toronto, Canada, among others. The state of Kansas purchased some, as did the Union Pacific Railroad and the Pacific Mail Steam Ship Company.

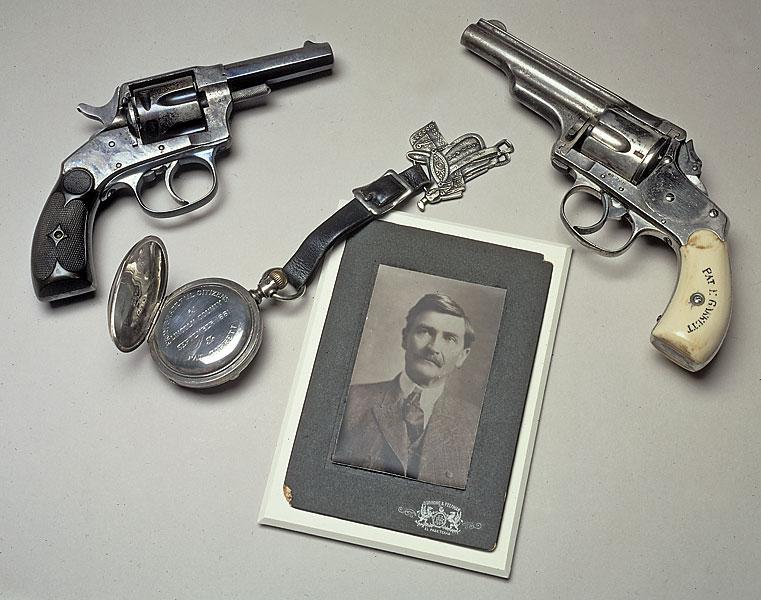

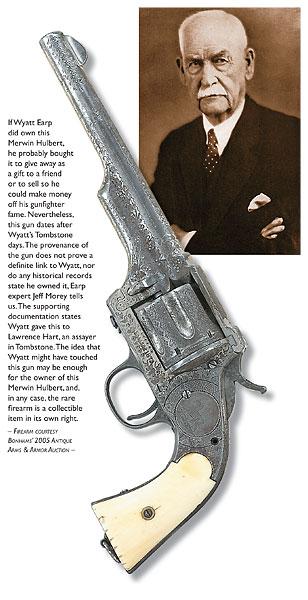

Merwin Hulbert six-guns have been attributed to well-known Old West figures as Jesse James, Pat Garrett, Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves, Indian Territory outlaw Bob Dalton and Arizona lady bandit Pearl Hart.

In the late 1870s, samples were also submitted to the U.S. Army Ordnance Board for testing and received favorable reviews. While no government contracts were ever signed with Merwin Hulbert, the firm did place several ads in the Army & Navy Journal, resulting in a number of private purchases by military officers.

As late as the early 20th century, Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, best known for doing away with the notorious duo, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, reportedly brought another bad man to justice when he fatally shot him with a .32 caliber Merwin Hulbert Pocket Revolver.

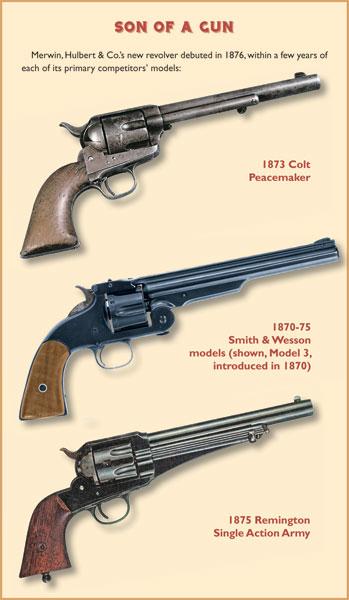

The Merwin’s popularity during the last quarter of the 19th century was such that the firearm company became the fourth-largest seller of American revolvers, behind Smith & Wesson, Colt and Remington (in that order).

As final testimony to the Merwin Hulbert revolvers’ acceptance and high quality, several foreign infringement imitations (of lesser quality) were produced in Spain and Belgium.

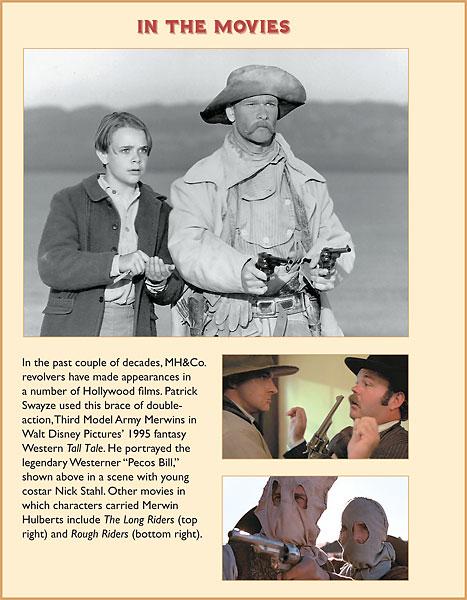

In recent years, with movie makers paying closer attention to period detail, these unique frontier-era revolvers have made a number of appearances in Hollywood films, such as 1974’s The Godfather: Part II, 1980’s The Long Riders and the 1997 TNT movie Rough Riders. As a gun coach, I personally selected a brace of double-action Merwin Hulberts to teach Patrick Swayze for his role as Pecos Bill in the 1995 Western Tall Tale.

Buying Merwins Today

In light of the increased interest in these fine old firearms, a new Merwin, Hulbert & Co. firm has been formed; it is currently working up tooling to reproduce Merwin Hulbert revolvers.

As for the firm’s collectible firearms, the number of different models and variations made during the mid-1870s to late 1890s make Merwin Hulbert revolvers a true collecting challenge. Good, functional specimens—sans any finish—can still be picked up for reasonable prices, but values have risen drastically in recent years, showing the Merwin’s investment potential. Merwin Hulbert revolvers that have retained most of their finish, as well as fancy engraved specimens, have, for the past couple of decades, been selling for premium prices, almost on a par with other long sought after arms such as Colts, Winchesters, Smith & Wessons, Remingtons and the like.

Merwin Hulbert revolvers are no longer thought of as the “ugly ducklings” of Old West six-guns. Rather they are receiving notable collector recognition for their part in taming America’s frontier, thanks to their distinctive styling, high quality of manufacture and their role in the overall evolution of the modern handgun. After more than 100 years since the last Merwin Hulbert revolver left the production line, collectors and arms historians alike are finally giving these fine old firearms the respect they truly deserve.

Phil Spangenberger writes for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

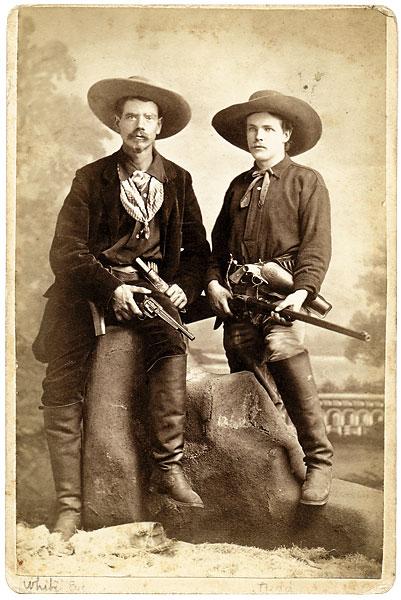

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

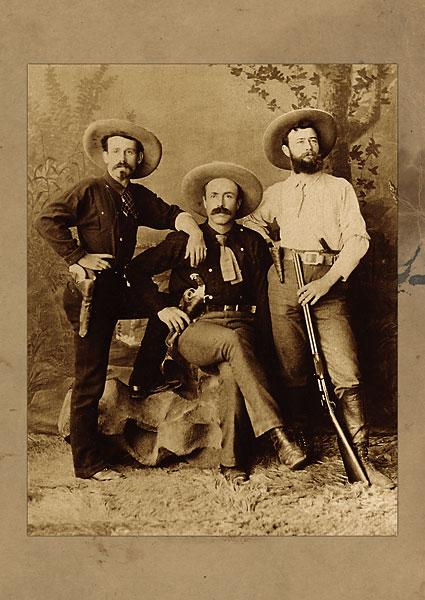

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

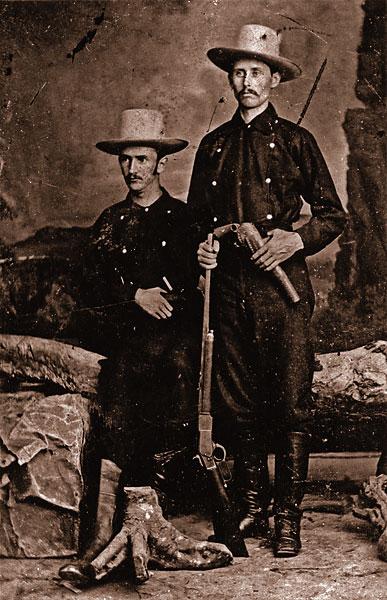

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

– All images True West Archives unless otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

– Courtesy Autry National Center; 85.1.437; 85.3.1; 85.1.511; 85.3.2 –

– Courtesy Rock Island Auction Company –

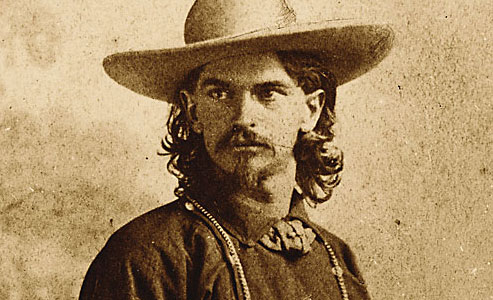

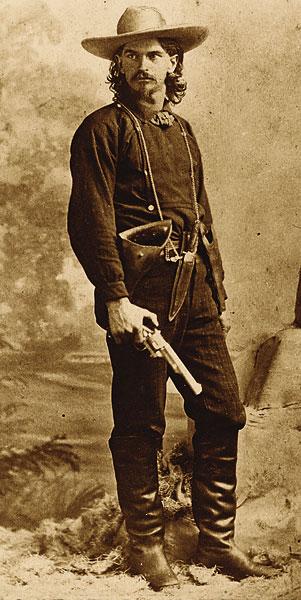

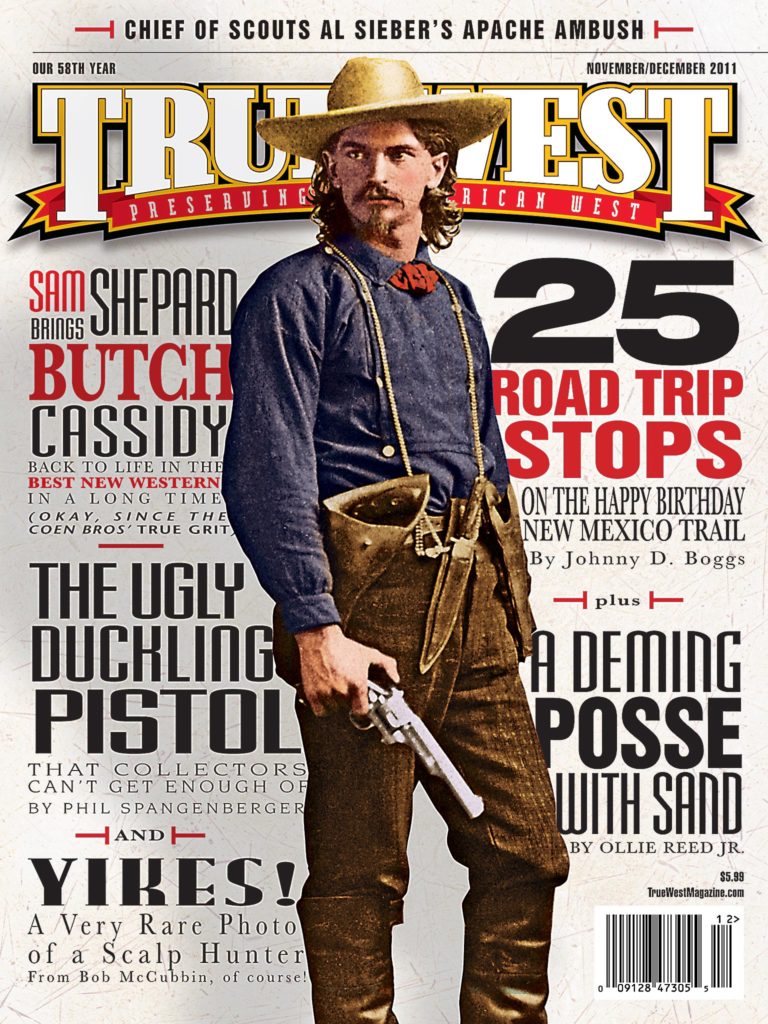

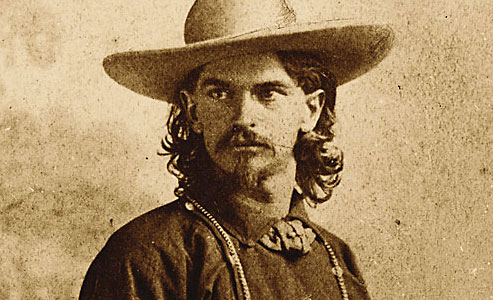

Wild Ben Raymond, who worked as a mine guard, posed for his photograph in Leadville, Colorado, holding a First Model open top Merwin Hulbert Frontier Army revolver. Although the arm is believed to have been a photographer’s prop, it nonetheless shows the Merwin’s presence in the Wild West.

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –