I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been asked the question: How come you Brits are so interested in the American West?

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been asked the question: How come you Brits are so interested in the American West?

And I know for a fact that the same question is asked of my German, Dutch, Italian, Swiss and even my Japanese friends. Obviously, we’ve all been influenced by the movies we saw as kids, by cap pistols and BB guns, by the games we played and the books we read and are still reading, and our visits, when we’ve made them, to the places where Wild Bill Hickok, George Custer, Wyatt Earp, Billy the Kid and Jesse James made their mark on history.

But the European fascination with the American West goes back a lot farther than our lifetimes. In fact, it’s been traced to the beginning of American history. Records show Native Americans were brought to England from Virginia as early as 1584; in 1606, five Abnakis from Maine toured the country. Although little written record of the 1606 visit survives, it can be confidently presumed they stopped traffic wherever they went.

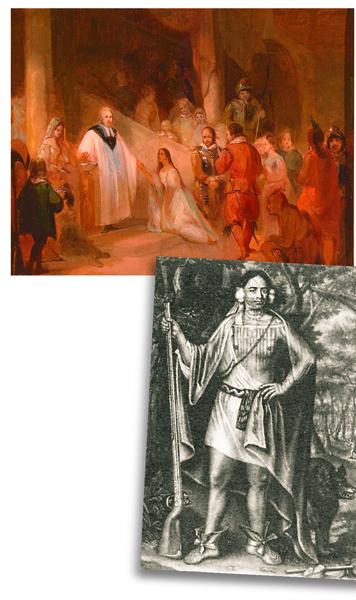

So it takes only a little imagination to picture the scene 10 years later, when one of the most celebrated Indian women of all time landed at Plymouth with 12 other Powhatan tribespeople: her name was Matoaka, better known as Pocahontas. Famous, thanks to Virginia settler John Smith, who, in his True Relation published in 1607 (could this qualify as the very first “Western?”), had shared his capture by the Powhatans, who sentenced him to death, only to be saved by the intervention of Pocahontas, then just a child. Clearly, British fascination with the vast, wild New World and its savage inhabitants dates back to this legend.

During her tour of England, Pocahontas was presented to King George and Queen Anne, and her portrait was painted by several renowned artists. By 1614, she had married Sir John Rolfe, one of the Jamestown settlers, and during her stay in England, she was socially known as Lady Rebecca Rolfe. When she died at the tragically early age of 21 after giving birth to a son, she was buried at St George’s Church in Gravesend, Kent. Among her descendants were Lady Edwina Mountbatten, Vicereine of India, and Lady Nancy Astor, the first female member of Parliament.

Our fascination with the Indians continued. Thayendanegea (a.k.a. Joseph Brant) was the leader of the Mohawks who sided with the British during the War of Independence, which began in 1775, the year he visited London. In 1818, a party of Creeks and Seminoles (also British allies during the War of Independence) visited London. In 1840, famed Indian artist George Catlin—who was to become the pre-eminent Western showman of his age—brought a contingent of Iowa Indians to London, staging “Tableaux vivants of the Red Indian” at Egyptian Hall, which were seen by over 30,000 people. These developed into two programs that received “loud and repeated acclamation.” One featured an attack, war dance, ambush, “dreadful” scalping, victory dance and reconciliation between the tribes. The second showed a shaman at work, Catlin painting Indians, a wedding, Pocahontas’ rescue of John Smith, wrestling, lacrosse, gambling and dancing.

In 1844, Catlin teamed up with George H.C. Melody, who had arrived in July with a party of Iowas. They performed before Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli and gave public performances at Lord’s Cricket Ground and Vauxhall Gardens. The following year, Catlin took his Indians to Paris, France, where a public already conditioned by James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales and Chateaubriand’s popular renditions of life in the American West flocked to performances at the Salle Valentino in the rue St. Honoré, a 150-foot hall that allowed the Indians to demonstrate their skill with bows and arrows.

Catlin’s career as a showman came to an end early in 1846. His Iowas had asked to return home, following the death of the wife and child of their leader. They were replaced by a band of 11 Ojibways, who performed before King Louis Philippe of France, who in turn recommended them to the King of Belgium. In that country, however, eight of the Indians contracted smallpox and two of them died. Stunned by their deaths—for he had campaigned vigorously against the exposure of American Indians to the white man’s diseases—Catlin never again mounted a Wild West show.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

It was not until 30 years later that William F. Cody, “Buffalo Bill,” took many of Catlin’s ideas and transformed them into a whirling, non-stop spectacle that embodied and celebrated the “romance” of the American West with its cowboys, Indians, sharp-shooters and trick riders.

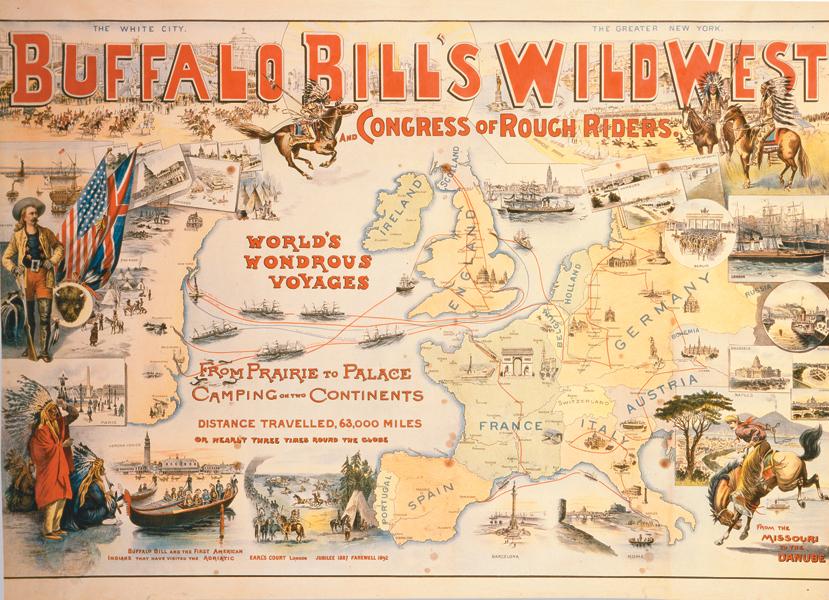

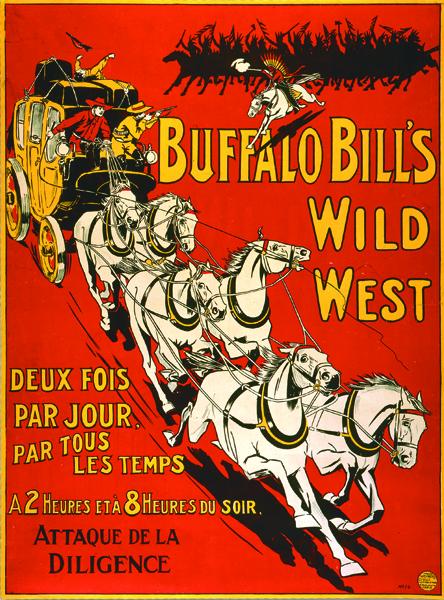

After huge successes in the U.S., Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show first came to England in 1887 during the ongoing celebrations for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. He brought the British a vision of the American West such as no one had ever imagined, let alone seen. Picture the crowd’s bedazzlement as four kings—of Denmark, Greece, Saxony and Belgium—were driven around the Earls Court arena in the Deadwood stage (with Buffalo Bill whipcracking away and Edward, Prince of Wales, beside him on the box). Imagine an audience that included not only the likes of you and me but the crown princes of Austria, Norway, Germany and Sweden, and the Duke of Sparta, the Duchess of Leinster, the Countess of Dudley, the Grand Duchess Serge of Russia, Princess Victoria of Prussia and Prince Louis of Baden, all attended by lords and ladies-in-waiting. So completely did its advent dominate public consciousness, so huge was its success, that virtually overnight, Buffalo Bill was a living legend. His Wild West show became the toast of not only England but, within a year, of Europe, as well.

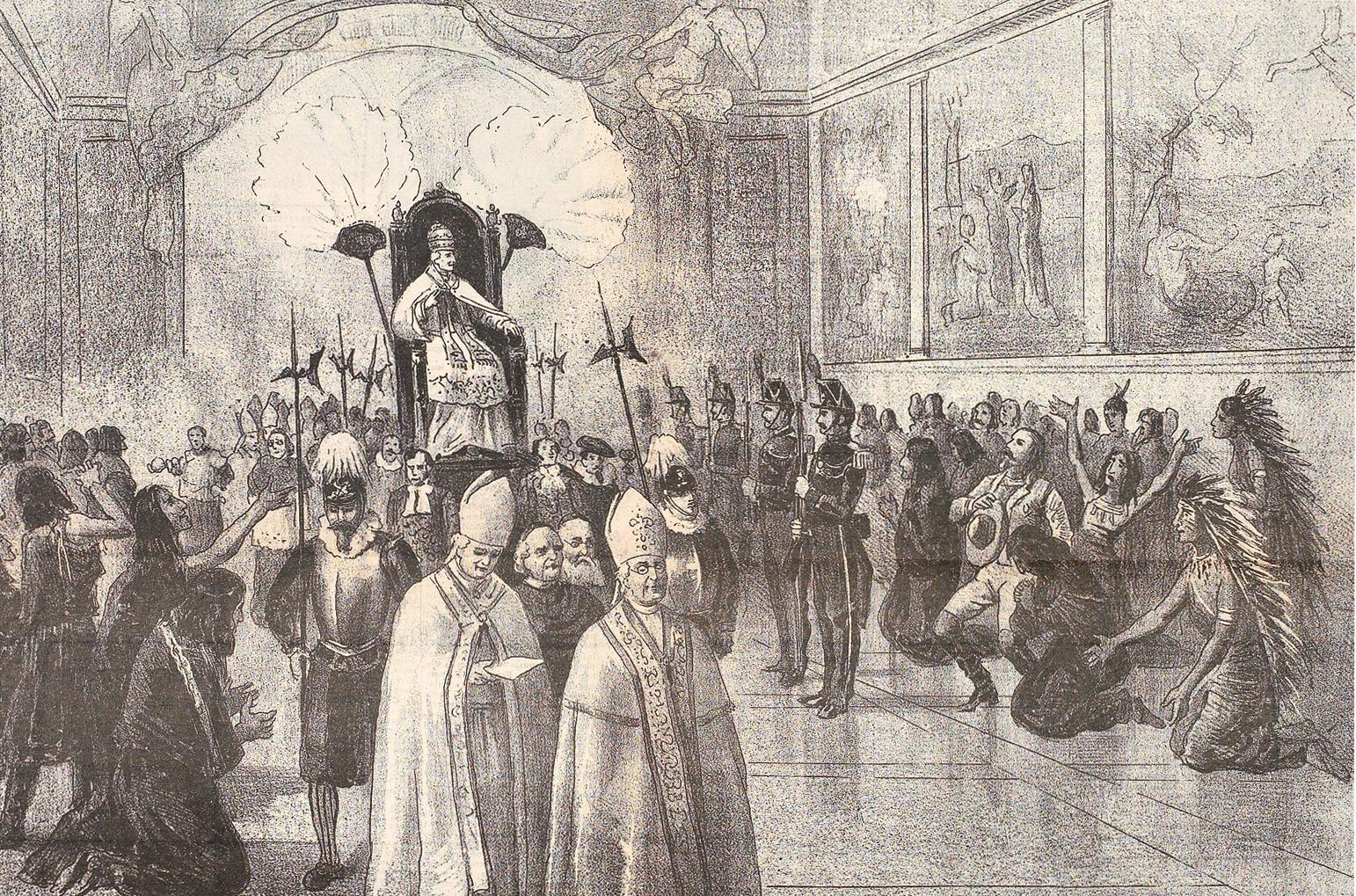

In 1889, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West returned to play London and to appear at the Paris Exposition (attended by 32 million people who came to see the newly-completed Eiffel Tower) and then went on to tour Europe: visiting France, Spain, Italy (with a special performance at the Vatican), Austria and Germany, where legend has it, Annie Oakley shot a cigarette out of the mouth of the future Kaiser Wilhelm. The Wild West show returned to England again in 1892, 1901, 1902, 1903 and finally in 1904, when the majority of the performances took place in Cornwall—the British Southwest. In 1905, they played the entire season in France: opening April 2 in Paris and closing November 12 in Marseilles.

Era of the Wild West show

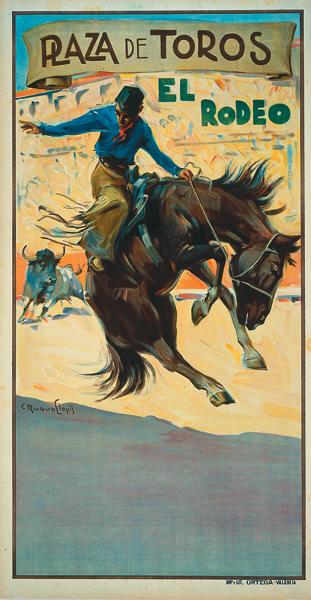

The show’s enormous success spawned a whole series of imitators. Doc Carver’s Wild West toured Europe and Australia, and lasted until about 1893; Adam Forepaugh added a circus element and invented a set piece called “Custer’s Last Rally”; Pawnee Bill’s Historic Wild West was big time after a failure or two. Colonel Frederick T. Cummins’ Miller Bros. 101 Ranch Wild West staged an Indian Congress at the Omaha Exposition in 1907 and later toured Europe. In all, there were about 125 Wild West shows on the road. In 1912, the Sarazani Circus was the first European show to feature real American Indians.

The era of the Wild West show came to an end partly because of restrictions imposed following the outbreak of WWI but, more specifically, because of the shows’ financial decline and the death of its inventor and finest practitioner, Buffalo Bill, who “went west” himself on January 10, 1917.

The Wild West shows dramatized the American West in Europe to a greater degree than had ever been done before, and they were, without question, the creator of the myth of the cowboy as a folk hero. The Western of fiction and motion picture that sprang to birth alongside it descended directly from the spectacle created by Buffalo Bill and his many rivals.

From the appearance in 1903 of the first movie, The Great Train Robbery (a Western, of course), and notably between the 1950-1970s, the Westerns boomed. A golden age of movies accompanied by a flood of novels made it one of the bestselling genres in publishing and library lending. It was quite common for a Western novel to sell a quarter of a million copies in paperback in England alone and dozens—both fiction and nonfiction—were published every month.

American West in today’s Europe

From the ranks of those moviegoers and readers were born re-enactment groups who dressed up in full cowboy or Indian regalia, maybe trying their hands at fast drawing and fancy shooting. In Germany, thousands of fans gathered (and still gather) at Bad Segeberg in Schleswig-Holstein to enjoy the annual Karl May Festival. Established in 1952, the festival shows movies that continue to be made about the adventures of “Old Shatterhand” and “Winnetou”—characters created in the 1890s by Karl May, an ex-convict-turned-writer who actually never set foot in the United States.

And the attraction wasn’t just found in Germany. Italy’s Emilio Salgari, Hungary’s Ferenc Belányi, France’s Gustave Aimard and England’s Capt. Marryat, G.A. Henty and Mayne Reid produced hundreds of sensational Western adventures. France’s George Fronval wrote 600 published books about the American West—54 of them about Buffalo Bill – between 1925 and his death in 1975. He was also a prime mover in Le Paris Western Club’s creation of a “Vallee des Peaux-Rouges” near Senlis, which featured “Redskins,” sheriffs and deputies, and even its own shooting range. In a more serious vein, and during this same time frame, a group that called itself the Westerners, dedicated to researching the facts behind the legends, was born in Chicago. Soon, other groups—Corrals, as they were called—sprang up all over the United States. In 1954, the first foreign Corral was formed in England, soon to be followed by others in France, Germany and Sweden.

In 1978, a young English entre-preneur named Derek Block saw a version of the Buffalo Bill Wild West Show revived a few years earlier by Montie Montana, Jr., in Canada. He liked it so much, he imported the show to play at Wembley Arena in London, with Rudy Robbins playing Buffalo Bill, Montie Montana, Jr., as announcer, half a hundred cowboys, almost as many Indians (Navajo, Maricopa, Hopi, Modoc, Osage-Pawnee, Sioux, Seneca, Cherokee), the Deadwood Stage, Australian whipcrackers and boomerang throwers, quick draw artists, gun expert Phil Spangenberger, Argentine gauchos, knife and tomahawk thrower Chief Grey Otter and trick and fancy rope throwers. But in spite of what Block described as “tremendous interest,” it was a disaster. Opposed on every front by Britain’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (“they jumped all over me,” Block said), Block was forbidden to let the cowboys rope and throw steers, or arrange stunts with falling horses in the restaging of Custer’s Last Stand. As a result, the audience got more of a tame show than a Wild West production—and Block lost £100,000.

Although the flood of novels and movies has dwindled now to a trickle, European interest in the American West continues to flourish. It’s almost as if, ever since Buffalo Bill first brought the Wild West to us, he left buried deep in the European psyche the yearning to be out there on the range, forever riding, forever free. As a result, Britain boasts leading authorities on gunfighters and outlaws, the military, the Indian wars and the cattle towns. Last November, the English Westerners Society, which publishes the quarterly Tally Sheet and annual Brand Books, celebrated its 50th anniversary; there is also a British Westerners group and a Custer Association of England, not to mention a full-blown

Western replica town in Kent called Laredo, complete with townsfolk and cowboys, as featured in the movie Finding Neverland.

Notable researchers and writers of the American West live in Switzerland, Belgium, Holland and Norway. In Germany, which boasts a serious historical quarterly called Magazin für Amerikanistik, you can attend a “Grosse Apache Live Show” on the Damerower See or a “Bisonfest” in Stuttgart, buy Indian tipis in Frankfurt or frontier-style clothing in Hamburg. Not too long ago, a Hungarian anthology featuring stories by Owen Wister, Bret Harte and Vardis Fisher sold 50,000 copies—one for every 500 citizens. Cowboy boots and jeans, and western-style clothing are commonplace anywhere from Scandinavia to Spain and from Prague to Dublin. What may be called “the non-American American West” is enjoyed today in South America, Australia, Turkey, Egypt, Israel, Czechoslovakia and Italy, Turkey and Japan.

The Old West lives on, but it doesn’t belong to just America anymore. It belongs to the world.

Frederick Nolan’s Tascosa:?Its Life and Gaudy Times will be published next year by Texas Tech University Press. He recently received WOLA’s 2005 Glenn Shirley Award for his lifetime contribution to outlaw-lawman history.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center / Cody, Wyoming / Gift of the Coe Foundation; 1.69.167 –

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center / Cody, Wyoming / Mary Jester Allen Fund; 1.69.6022 –

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center / Cody, Wyoming / P.69.822 –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center / Cody, Wyoming / P.69.972 –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center / Cody, Wyoming / MS6.IX.6.2 –