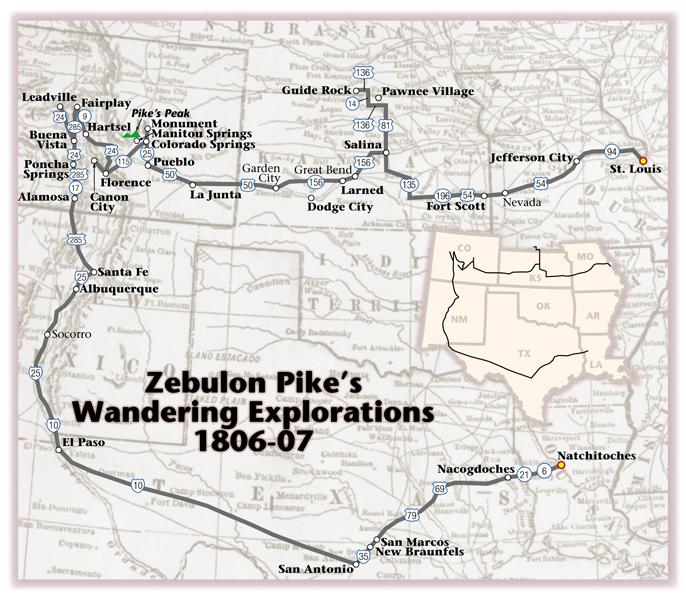

I guess you could say Zebulon Pike made a grand circle tour in 1806-07, although that wasn’t his intention when he set out on a reconnaissance of the Louisiana Purchase in July 1806.

I guess you could say Zebulon Pike made a grand circle tour in 1806-07, although that wasn’t his intention when he set out on a reconnaissance of the Louisiana Purchase in July 1806.

The explorer organized his crew of 19 enlisted men, including interpreter Antoine Baronet Vasquez, physician John H. Robinson, Lt. James B. Wilkinson (son of Louisiana governor James Wilkinson) and 51 Indians, including eight who had just returned from Washington, D.C., where they had been guests of President Thomas Jefferson. With them, Pike intended to explore the southern portions of the Louisiana Purchase. He would seek out the headwaters of the Arkansas River, find the source of the Red River and return home.

He had a few other objectives for the trip: negotiate a peace between the Kansas and Osage Indians, find and negotiate with the Comanches, study the natural resources and make scientific observations. Oh, yes, he was also to “scout” as close to Santa Fe as possible, gathering intelligence for the United States although that wasn’t a mission approved by the War Department until after the fact.

Taking a direct route didn’t figure into his plans. Intentionally, he would range north and then back south. Unintentionally, he ended up in Mexico as a captive “guest” of the Spanish authorities.

Louisiana Gov. James Wilkinson, in collusion with Aaron Burr, almost certainly intended for Pike to gather intelligence that could lead to a power play for Wilkinson and Burr to control what is now the American Southwest. The jury is still out on whether this was a deliberate attempt to separate those Western territories from the U.S. or undertaken in a desire to wrest control of the region from the Spaniards without officially involving the United States. Either way, Pike played into Wilkinson’s scheme so much so that by the time he fell under control of Spanish authorities, he actually may have been lost, which had been the cover story he and Wilkinson concocted before the journey began.

Trailing the Lost Pathfinder

Leaving from Fort Belle Fontaine, today’s Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, the party used the Missouri River as a conduit across eastern Missouri with camps near such present-day communities as St. Charles (July 17, 1806), Washington (July 20, 1806) and Hermann (July 24, 1806). The route turned toward the southwest at the confluence of the Osage River and the Missouri since Pike, intent on establishing relations with tribal groups and returning former hostage Osages to their home territories, took a route up the Osage. To follow Pike’s route across Missouri, begin in St. Louis and travel west on highway 94 to Jefferson City and then take U.S. 54 to Fort Scott, Kansas.

Pike’s entourage crossed into Kansas in early September, where he camped north of present-day Fort Scott before following the Little Osage River to the Neosho, generally traveling due west with campsites south of Emporia and near Marion. (Take U.S. 54 and Highway 196 west to 135 then travel north to Salina.) Diverting from his westerly course near Salina, Kansas, Pike took a route almost due north (U.S. 81) eventually striking the Republican River in present-day southern Nebraska, where he ran up an American flag at his campsite of Sept. 25-Oct. 6 at a location west of Guide Rock (off U.S. 136). Pike then reversed his march, traveling almost due south during the next 10 days to eventually reach the Arkansas River, again near Salina. There he also did a bit of wandering before he resumed his westerly explorations. His route across Kansas and Colorado remained close to the Arkansas River with a stated intent of finding its source. Much of this route would eventually become the path of the Santa Fe Trail. Follow Pike’s route by traveling west along Highway 156 and then on U.S. 50 through western Kansas and into Colorado.

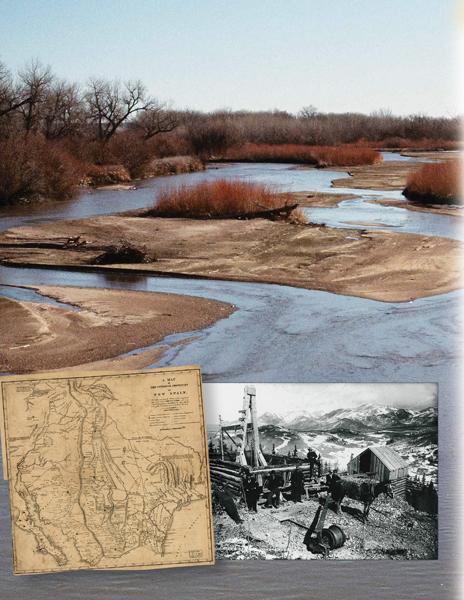

On November 15, from camp on the Purgatoire River, a mile upstream from its confluence with the Arkansas River in the vicinity of La Junta, Colorado, Pike first saw the Rocky Mountains and the peak that now carries his name. He wrote: “At two o’clock in the afternoon I thought I could distinguish a mountain to our right, which appeared like a small blue cloud. . . . When our small party arrived on the hill they with one accord gave three cheers to the Mexican mountains.”

Three days later, his party killed 17 buffalo, leading to a temporary rest during which the men spent time drying the buffalo meat while their horses grazed and recuperated from the already long journey. Resuming their travels, they encountered a party of Pawnees on November 22. Pike gave the natives “a carrot of tobacco, one dozen knives, 60 fire steels and 60 flints.” The Pawnees responded by demanding ammunition, corn, blankets and kettles, which Pike refused to provide.

Although the initial exchange was relatively friendly, it soon became clear that the Pawnees resented the military party. “The affair began to take a serious aspect,” Pike later wrote. He ordered his men “to take their arms, and separate themselves from the savages; at the same time declaring to them, I would kill the first man who touched our baggage.” In spite of Pike’s caution, the Indians secured a sword, tomahawk, broad axe, five canteens and other small items before the two groups separated.

The party continued west, reaching today’s Pueblo, Colorado, on November 23 and there building a defense area of logs recognized as the first structure ever built by Americans in Colorado. Again Pike took a detour, traveling northwest along the Front Range of the Rockies, headed toward the highest peak in the range—one that would eventually become Pike’s Peak although he never set foot on it.

He camped below the massive mountain he called Grand Peak on November 26 and then retreated south, writing on November 27, “I believe no human being could have ascended to its pinical [sic]. This with the condition of my soldiers, who had only light overalls on, and no stockings, and every way ill provided to endure the inclemency of the region; the bad prospect of killing anything to subsist on, with the further detention of two or three days, which it must occasion, determined us to return.”

Pike’s party regrouped along the Arkansas, near what became Pueblo, and turned west again in early December. At Canon City, Pike abandoned the river and struck out north on a trail left by Spanish cavalry. The track petered out, but Pike made it into the mountains west of Pike’s Peak, a region that eventually developed into an important mining district. By December 14, he reached the South Platte River, which he correctly identified.

He followed the South Platte upstream near the present-day town of Fairplay before zigging south to present-day Buena Vista where he again struck the Arkansas, which he mistakenly thought was the Red River, causing him to zag north seeking the headwaters before a zig south along the river. He spent Christmas eating buffalo in the snow at a site near present-day Salida before turning east through the Royal Gorge and back to Canon City where he did not want to be.

Still seeking the Red River, he then diverted southwest down Grape Creek across today’s Great Sand Dunes National Monument and ultimately to a site near the confluence of the Conejos River with the Rio Grande south of present-day Alamosa, Colorado, where he built a structure known as Pike’s Stockade.

Still Lost!

From La Junta, I trail Pike west to Pueblo on U.S. 50, then turn north on I-25 to Colorado Springs and Monument. Unlike him, I reach the top of the peak that bears his name by taking the Pike’s Peak Highway to the summit for a grand view of the Colorado Rockies. In order to stay on his circuitous route, I retrace both my travels and his steps by taking Highway 115 from Colorado Springs to Canon City. From there, I head north to U.S. 24 where I turn west to Hartsel and then drive north on Highway 9 to Fairplay before taking U.S. 285 back south across South Park to Buena Vista.

By now, I’m nearly dizzy in following this trail of his and am beginning to realize just how ridiculously lost he became (I might use the word inept, but perhaps that is a bit harsh; after all I have a map to follow and Pike didn’t even have a general feeling for the region). Sticking to Pike’s trail, I turn north along the Arkansas taking U.S. 24 to Leadville where I take a much needed break for some refreshments (no doubt he would have liked to have such an opportunity), before back-tracking south on U.S. 24 to Poncha Springs. Now, I could continue east on U.S. 50 to Canon City but instead, I avoid his blundering route and take U.S. 285 and Highway 17 through the San Luis Valley to Alamosa.

Pike crossed through what is now Great Sand Dunes National Monument before establishing his second fortification in today’s Colorado, a place known as Pike’s Stockade. He was in Mexican lands, making it perhaps inevitable that Spanish soldiers would find him there. Of that discovery, Pike wrote in his journal, “I immediately ordered my flag to be taken down and rolled up, feeling how sensibly I had committed myself, in entering their territory, and was conscious that they must have positive orders to take me in.” He was right about the orders. He soon found himself being escorted south into New Mexico and eventually to El Paso del Norte and into Chihuahua for an interrogation.

To follow Pike’s route in the United States from Alamosa, head south on U.S. 285 to Santa Fe, then pick up I-25 and continue south along the route of the El Camino Real (The Royal Road) to El Paso. There I highly recommend a stay—or at minimum a drink—in the Camino Real Hotel before you turn east and begin the long, long drive across Texas.

By early June 1807, he was back north of the Rio Grande on an escorted trip across Texas that took him past Carrizo Springs to the mission at San Antonio, where he and his men were treated kindly before they were taken on a northeasterly path across Texas to Natchitoches, Louisiana. There the Spanish authorities allowed the men to go home.

On the Pike trail across Texas (from El Paso head east on I-10), you’ll definitely need some breaks and should plan to take one in San Antonio where you can visit the restored Alamo and other missions that hosted Pike, dine or stay at the Menger Hotel and enjoy some food, drinks and entertainment along San Antonio’s Riverwalk. From San Antonio, continue northeast on I-35 through New Braunfels (Pike was here June 13, 1807), San Marcos (June 14, 1807, campsite), and then take U.S. 79 and U.S. 69 to Nacogdoches (June 27, 1807, campsite). From there, continue east on Highway 21 to cross into Louisiana and follow Highway 6 to Natchitoches.

In spite of his at times random wandering, Pike did correctly map the locations of the Arkansas, Red and South Platte Rivers, providing information that would be critical in the westward expansion of the United States. Like Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery, Pike and his men explored a large portion of the Louisiana Purchase. But unlike the Lewis and Clark company, they were not greeted with appreciation upon their return. Instead, they came back under a cloud of suspicion related to the Wilkinson-Burr conspiracy. As a result, they didn’t receive extra pay nor land grants for their service.

Photo Gallery

Pike drew up this map (left) of New Spain from his time spent as a captive in Mexico before he was released and taken back into Louisiana

– Below: By Clive Siegle; Inset: True West Archives –

– All images by Clive Siegle unless otherwise noted –