In the Arizona wilderness of 1881, 20-year-old courier Frederick Russell Burnham knew that the assignment from Neil McLeod, one of Tombstone’s many larger-than-life personalities, was fraught with danger. The Apaches were on the warpath, and McLeod, a smuggler and prizefighter, desired to send a message to associates in the Mexican state of Sonora. Burnham, who considered McLeod a mentor, readily accepted the dangerous assignment

Outfitted to appear uninteresting to Arizona’s human predators, with a bony horse, a beat up saddle, a canteen, a bag of cornmeal, a bag of barley, jerky and a sawed-off Colt pistol, Burnham rode into the backcountry, headed for a message drop location at Cabeza Borago in Sonora.

With Geronimo and other “broncos” then raiding the countryside, the mission bordered on foolhardy. One careless move and Burnham might wind up dead or even worse, captured. The Apaches were renowned for inflicting a variety of tortures upon those unfortunate enough to fall into their hands while yet living.

Burnham easily made his way to the drop site, where he buried a brass matchbox containing the message and lit a fire above it. When the message was picked up, an answering fire would inform the young courier. When he saw the fire on the third night, he started for home, about an hour before midnight, riding west of Fronteras.

At daylight he halted at a Mexican ranch, hiding his horse where it could feed on the sparse grasses and taking an opportunity to take a nap atop a rocky ridge. He took precautions like caching his food and his tack while keeping his canteen, gun, field glasses, leggings, and Mexican moccasins (tawas) on his person.

Burnham’s calm was shaken when he heard something moving nearby. The unmistakable sound of a cloth-covered canteen bumping against a rock told the young man much about his visitor. He deduced his unseen visitor must be a reservation Apache and, as such, the man likely was armed with a military rifle.

When the Apache moved toward Burnham’s hiding place, the two waltzed among the heavy brush, as Burnham left to silently swap spots with the approaching Apache. When he slipped past the scout, though, he found his escape route “alive with Apaches.” A war party was dividing booty from a raid on a nearby ranch. Burnham’s sawed-off Colt barked and started a general pandemonium. He fired several shots before tearing through the underbrush as fast as his strong legs could carry him.

Literally running for his life, Burnham plunged off a short cliff, losing his hat and canteen in the process, with his fall broken by a mesquite bush. Envisaging trackers following his every move, he abandoned his bony horse and steeled himself for a long race against the agile Apaches. Much to his chagrin, but fortunate for his survival, the valley before him sported dense patches of cholla, a desert plant that deterred even the Apaches. Running through such thorn patches was akin to swimming across a piranha-infested river in the jungle.

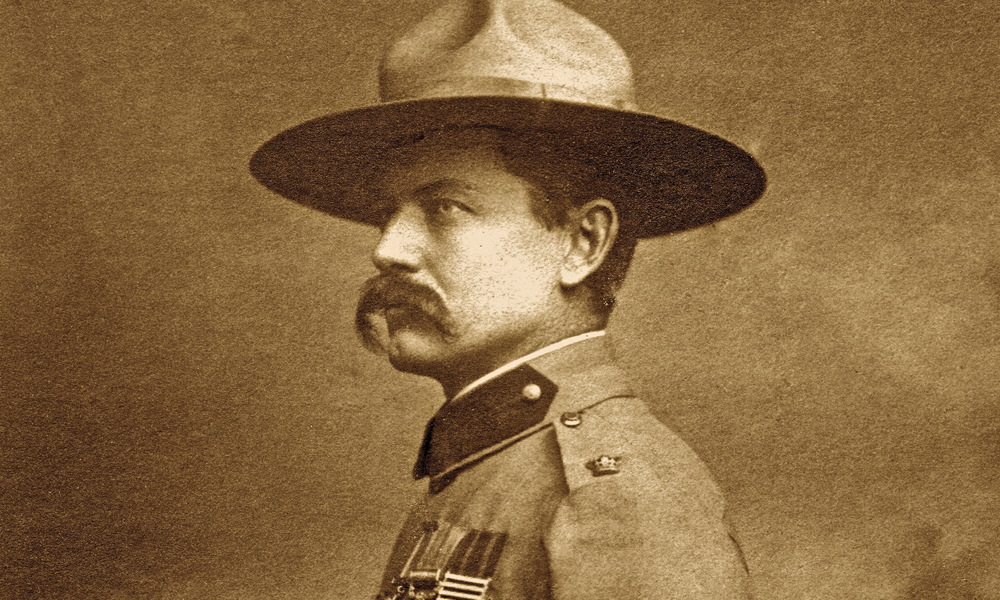

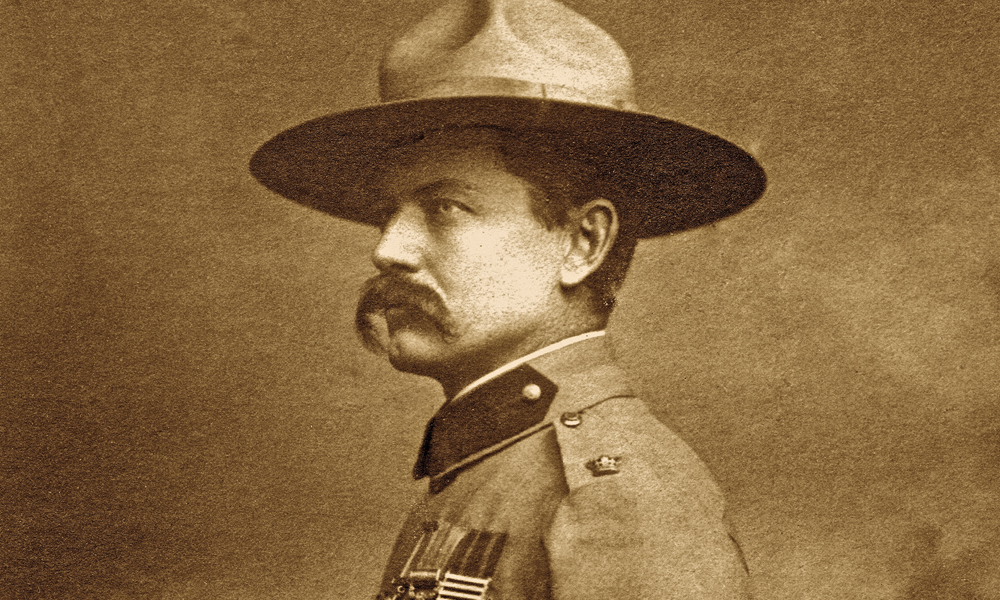

Hearing a shrill Apache war cry close by, he ran his heart out. The sunburnt, thorn-scratched Burnham covered roughly 100 miles of Apache-controlled territory to Tombstone, hatless and without a canteen. This tale was only one of many survival stories in his life. As a baby, he was hidden by his mother in a basket of corn husks during the Dakota War of 1862. He performed his first scouting, for the War Department in 1881, when he was hired by Albert D. Sterling, the San Carlos Reservation chief of police. Given his successful run for his life that year, Burnham is best summed up by Capt. S.L. Burbridge’s first impression of the young man: “I’m looking for a scout who is half jackrabbit and half wolf, and by the eternal blazes I believe you are it.”

Terry A. Del Bene is a former Bureau of Land Management archaeologist and the author of Donner Party Cookbook and the novel ’Dem Bon’z.

– True West Archives –